by Sarah Mines ‘24.5

In this paper, I examine storytelling as a method for decolonization and indigenization within the framework of Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s 25 Methods of Decolonization and specific examples of Indigenous activism. I must acknowledge that I am a white woman raised on stolen land who has never had to personally face the challenges that come with being a BIPOC individual in the United States. Because of my privilege and identity, I have a responsibility as an ally to stand with, listen to, and help Indigenous activists in their efforts to decolonize our society. Additionally, my writings and claims are distinctly my own and I do not pretend to speak for the Abenaki people nor any other Indigenous groups.

Decolonization is the practice of removing or dismantling colonial elements in a culture, society, nation, or one’s own mind, especially concerning the lives and experiences of Indigenous people. However, in the United States and Canada, there exists a form of colonialism in which colonists attempt to replace indigenous communities: a settler-colonial state. This state exemplifies the need for decolonization because facets of colonization continue to occur both interpersonally and at a systemic level within colonized nations. An adjacent approach to decolonization may provide a more effective and long-lasting solution: Indigenization. Indigenization differs from decolonization in that it prioritizes meaningful, and distinctly Indigenous-based change by rejecting “tokenistic gestures of recognition or inclusion.” Through this method, Indigenous communities reclaim power and by using Indigenous methods to rewrite colonial narratives and create lasting systemic change (“What is Decolonization”).

Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Indigenous writer and member of the Ngāti Awa and Ngāti Porou iwi tribes, writes that Indigenizing has two distinct projects: disconnecting settler society from its metropolitan homeland and recentering political and cultural action around Indigenous identity and traditions. Tuhiwai Smith writes that it is largely the work of non-Indigenous folks to cut cultural ties between the land and settler society, but that the reframing of political activism and discourse in the context of Native issues is an Indigenous project (146). Storytelling, one of Tuhiwai Smith’s Twenty-Five Indigenous Projects, is a powerful tool for Indigenization because it allows for the rewriting of colonial narratives and reframing of historical events within the context of Indigenous lives and communities. Smith explains that this is because each story is powerful and offers a unique perspective. She adds, however, that the greatest impact and exertion of influence into the decolonization discourse comes from the collective story, built by many voices, in which every Indigenous person has a place (144-45).

In the Native Presence and Performance First-Year Seminar final research project, it was important for us to include Abenaki legends, stories, and interviews throughout the various sections of the blog to minimize our influence on the narrative of the blog. It is imperative that we, as non-Indigenous writers, take the time to educate ourselves and acknowledge how our perspectives impact our work, and actively work to decolonize our understanding of our place within this project and academia. Phoebe and I chose to include Middlebury College’s land acknowledgment in the introduction to the blog on the home page. This serves to inform the audience about the rightful inhabitants of this land and to challenge the default colonial, Judeo-Christian narrative about the origins of our land and country. However, Kara Stewart, writer and member of the Sappony tribe, asserts that researching the tribe and their history before writing about them is not enough. Stewart says,

If you are not Native, you may not be familiar with the thriving world of Indian Country today. Make yourself familiar with it. If you are not a member of the tribe you intend to write about, you need to find a way to immerse yourself in their culture. This could be tricky if you don’t know them. But it needs to be done. You need to tell them who you are, why and what you intend to write about them. Do not expect them to welcome you with open arms. You need to learn all you can from them. And you need to respect what they say (“Writing About”).

In summary, the telling of Indigenous stories is a highly sacred process that belongs to the original storytellers. As an editor of the blogs done by the Native Presence and Performance First-Year Seminar and as a non-Indigenous person, this message holds resounding truth and offers a personal challenge of taking extra steps as to not spread Indigenous work as our own. When we share Indigenous stories and information, it may only be done with permission, cultural immersion, and respect.

The sharing of individual stories in addition to collective stories or legends also serves to fight against the imperial process of homogenization (Sium and Ritskes 2). Sium and Ritskes say that “by telling our stories we’re at the same time disrupting dominant notions of intellectual rigor and legitimacy, while also redefining scholarship as a process that begins with the self” (4). In essence, the sharing of stories by Indigenous people combats imperial efforts of erasure because storytelling and bearing stories is an inherent expression of existence (Sium and Ritskes 6). in addition to fostering interpersonal connections and bonds, traditional story sharing allows for members of the community to teach about cultural beliefs, relationality, values, customs, rituals, history, practices, relationships, and ways of life (Datta 37). Datta says that storytelling has been used by many Indigenous cultures for thousands of years and is integral in a community’s understanding of the world, human purpose, and spirituality.

Historically, the use of traditional Western research methods in exploring Indigenous perspectives has “often been felt by the Indigenous people themselves to be inappropriate and ineffective in gathering information and promoting discussion” (Datta 1). Western techniques are often highly rational and individualistic which, when working with Indigenous communities, are ineffective because they are fundamentally incompatible with the Indigenous understanding of the world. Indigenous research differs from Western research in that it includes “a connection to Indigenous knowledge, a location within an Indigenous paradigm, a relational nature” and its purpose is most often to decolonize (Datta 36). Additionally, Indigenous methods tend to follow a structure that is reflective of Indigenous knowledge and values of the community, such as flexibility, collaboration, and reflexivity (Datta 36). In going forward with initiatives to Indigenize the United States and Canada, it is imperative to utilize Indigenous methods because they “preserve Indigenous voices, build resistance to dominant discourses, create political integrity, and most importantly, perhaps, strengthen the community” (Datta 36). By relying on Indigenous practices such as storytelling as a method of decolonization, the process is more authentic to the Indigenous experience in a colonized state.

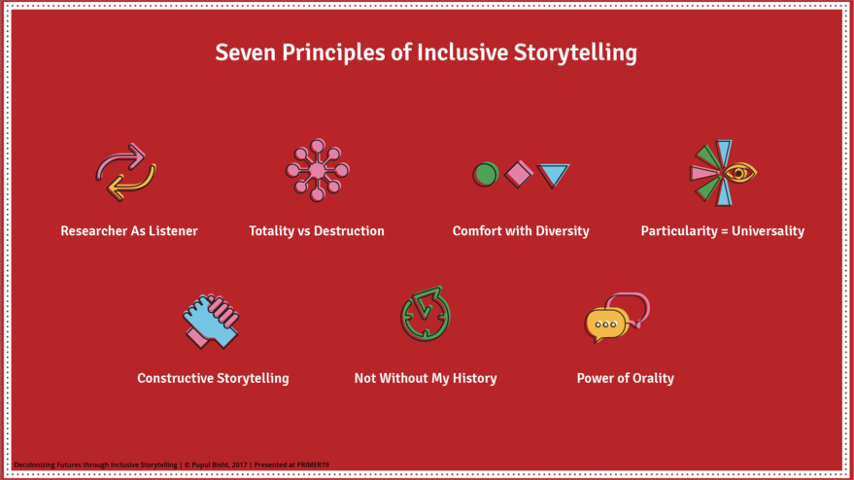

For example, designer and researcher Pupul Bisht uses storytelling as a way to decolonize and reframe colonial narratives in the speculative design industry. While working on her master’s degree, Bisht began to research how the stories communities told related to their outlook on the future. She found that what “we tell matter[s] a lot because they ultimately shape our sense of reality, our worldview. If we talk about something with a sense of urgency and fear, then our attitude towards that thing is going to be shaped by those emotions” (Fonder). She says that when people can tell stories and talk about the future with a sense of autonomy, they are not only empowered but feel that they have a hand in shaping what is to come (Fonder). The element of autonomy and the ability to own one’s narrative in the decolonization process is essential because Indigenous and marginalized folks can reclaim their stories and history. In her research, Bisht’s methods center around her Seven Principles of Inclusive Storytelling. She warns, however, against co-opting her methods or standardizing her practices because she believes that a “one size fits all” approach colonizes research.

Storytelling also keeps stories of resistance, survivance, and colonization from an Indigenous perspective alive within these communities. The intimate and participatory nature of oral storytelling opposes colonial efforts to erase and rewrite Indigenous history within educational and government systems. For example, the state of Vermont did not recognize the Elnu, Koasek, Missisquoi, and Nulhegan Abenaki tribes until 2011 and 2012. And even then, Chief Don Stevens of the Nulhegan band says that there is still much work to be done to garner proper support and to educate state residents about Indigenous people and groups within the state. In an effort to spread awareness about Abenaki history and culture, Jeff Benay, Director of Indian Education for Franklin County, offers informational classes, after-school programs, and educational materials to all students and educators at no cost. Benay says that the darker side of Vermont’s history, such as forced sterilizations and eugenics projects, has been largely forgotten because it isn’t consistently taught in schools. He argues that improving Indigenous curriculum and sharing of Indigenous narratives will “pave the way for better relations with Abenaki tribes in the future” (Gringas).

My research on the importance and sanctity of storytelling has greatly informed my role as an editor of the blog. I hope to challenge myself and others to connect with Indigenous communities, ask for permission before sharing information, and write our blogs from a place of humility. To conclude, Indigenous stories and history are necessary for our modern systems to become more inclusive and historically accurate. Achieving this, however, requires intentional, intersectional work and activism with native voices leading the charge.

Works Cited

Datta, Ranjan. “Traditional Storytelling: an Effective Indigenous Research Methodology and Its Implications for Environmental Research.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, vol. 14, no. 1, 2017, pp. 35–44., doi:10.1177/1177180117741351.

Fonder, Allison. “Pupul Bisht Wants to Decolonize the Future of Design Using Storytelling.” Core 77, 26 July 2017, https://www.core77.com/posts/89278/Pupul-Bisht-Wants-to-Decolonize-the-Future-of-Design-Using-Storytelling, Accessed 28 April 2021.

Gómez, Leila. “Introduction.” English Language Notes, vol. 58 no. 1, 2020, p. 1-8. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/758825.

Gringas, Abbey. “Vermont Abenaki build cultural awareness.” Burlington Free Press, 4 Sep. 2016, https://www.burlingtonfreepress.com/story/life/2016/09/04/vermont-abenaki-identity- culture/88290830/. Accessed 4 May 2021.

Sium, Aman and Eric Ritskes. “Speaking Truth to Power: Indigenous storytelling as an Act of Living Resistance.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 2, no. 1, 2013.

Smith, Linda T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London, Zed Books, 1999.

Stewart, Kara. “Writing About Native Americans.” From Here to Writernity, http://writernity.blogspot.com/2016/03/writing-about-native-americans.html. Accessed 22 April 2021.

“What is decolonization? What is Indigenization?.” Center for Teaching and Learning. Queen’s University, https://www.queensu.ca/ctl/teaching-support/decolonizing-and-indigenizing/what-decolonizationindigenization. Accessed 28 April 2021.