Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s recent broadside blasting President Obama for his failure to fulfill his promise to govern in bipartisan fashion is merely the latest such charge leveled by leaders of both parties on this topic. Predictably, Democrats responded that it is Republicans who are being obstructionist by refusing to meet Obama’s bipartisan overtures halfway.

Neither perspective is correct. Instead, as I have argued since before Obama’s inauguration, there was never much probability that we would see a decline in the partisan polarization that has characterized presidential-congressional relations during both the Clinton and Bush administrations, Obama’s best intentions to the contrary notwithstanding. Change, in this case, means more of the same. And the reason has almost nothing to do with Republican desires to “wreck” Obama’s presidency any more than the polarization during Bush’s presidency can be blamed on Democratic efforts to thwart his leadership. Nor should we accuse Obama – as many critics have – of pulling a bait and switch on American voters; although many Republicans view his calls for a more bipartisan relationship as insincere, I think he was (and continues to be) strongly committed to finding a middle ground on which Democrats and Republicans can come together to address the nation’s problems.

The problem, of course, is that there is no such middle ground on most issues, particularly those pertaining to the economy and the budget. Democrats and Republicans are polarized because they do not agree on how best to solve problems related to the economic recession, health care, the energy crisis, or cap and trade emissions policies, to name only a few pressing issues. Faced with this lack of agreement, Obama is essentially powerless to broker a bipartisan compromise on any of these fronts. If he moves Right to attract Republican votes, Democrats rebuke him. If he sides with his party, Republicans accuse him of bargaining in poor faith. Given these two unpalatable options, I have predicted from Day 1 that Obama would, on most polarizing issues, opt for going with his party majority, just as George Bush ultimately opted to govern primarily (albeit not exclusively) through the Republican majority, until he lost that majority in 2006. .

But what of the 2008 election results? Didn’t they indicate Americans’ desire for change in the form of a more bipartisan governing stance? Participants at a recent talk I gave on a paper I wrote about the lack of bipartisanship under Obama made essentially this claim in taking my argument to task. Republicans’ obstructionism, they argue, runs contrary to prevailing public opinion. Americans voted for change, and Republicans are out of line for not recognizing this. This line of reasoning fundamentally misreads how our political system works and what the 2008 election results signify. Ours is not a parliamentary system whose members are selected from party “lists”. Nor is it a “presidential” system in which the president’s election dictates what voters believe Congress will (or should) do. Rather, we are governed by a congressional system, in which Senators and Representatives represent geographically distinct locales. And for most Republicans (and not a few Democrats) the most recent elections did not signal a commitment to bipartisanship if that meant abandoning party principles. Consider the following graph.

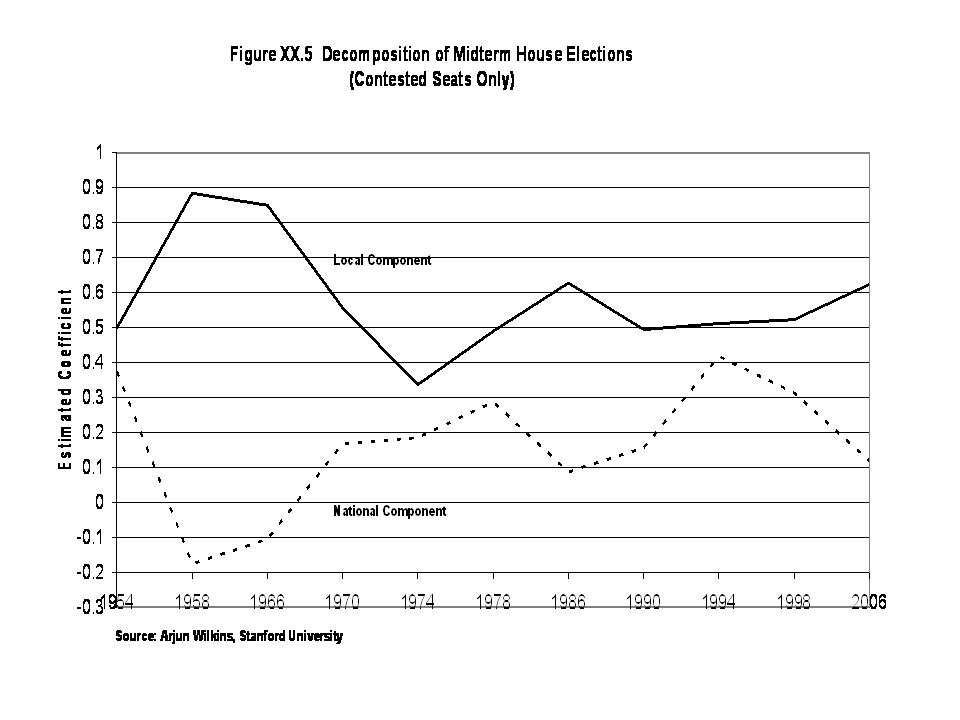

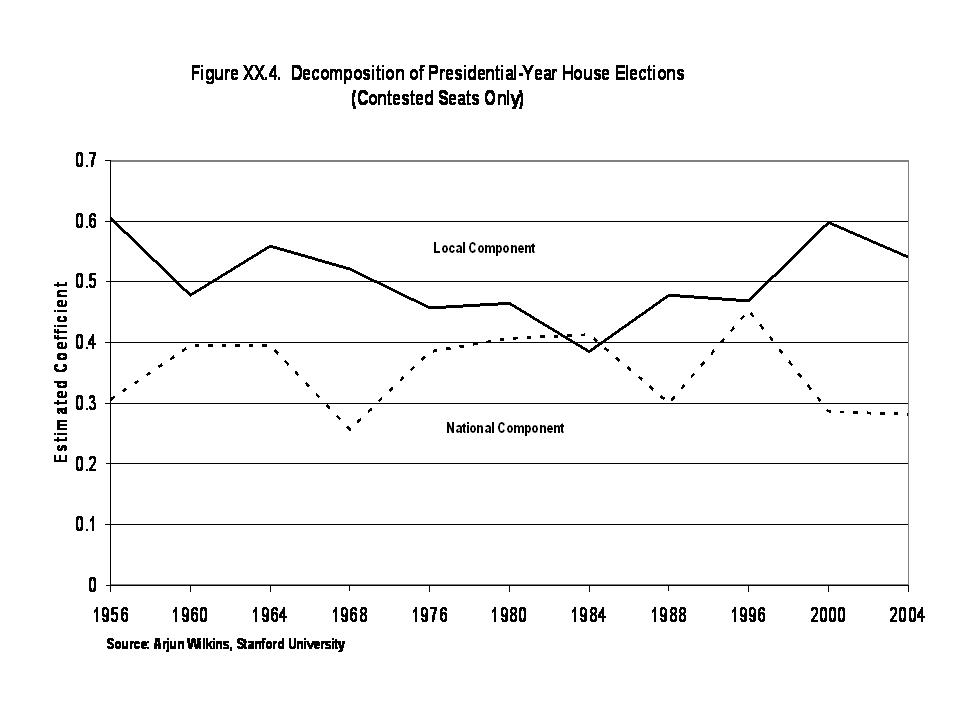

It shows the relative influence of “local” versus “national” forces on midterm congressional elections during the period 1954-2006. Most notably, even in 2006, which most pundits interpreted as a midterm election that was largely a referendum on the Bush presidency, the impact of “local” factors dwarfs “national” factors in explaining House results. (I urge those interested in how these figures are calculated to email me at dickinso@middlebury.edu and I’ll take you through the process. I’m currently working to calculate the 2008 results and will present them when I can). The same pattern is revealed when looking at presidential election years; local forces typically outweigh national forces in determing the outcomes of House elections. Note, in particular, the 2004 election.

The point, I hope, is clear: members of Congress respond to different political incentives than does Obama because they represent different constituencies. Even in years when national tides run strong, as in 2004 and 2006, the primary influences on House elections are still local forces. So while it is true that most voters want Obama to govern in bipartisan fashion, they also want their elected Representative or Senator to stick up for local interests. And that often means espousing party principles, at the risk of appearing partisan. That’s why Obama failed so miserably at keeping earmarks out of his budget proposal – his interests were trumped by the interests of members of Congress looking to the needs of their own constituents. Given these incentives, Obama decided to declare victory and move on, rather than upholding his campaign pledge to end the use of earmarks and opposing the bill. It was a pragmatic decision.

As further evidence of the difficulty Obama faces in developing bipartisan congressional voting coalitions, consider the following data (see here). Congressional Quarterly has calculated that only 19% (83) of the 435 House districts split their vote by supporting a member of one party for the House and the presidential candidate of the opposing party. Similarly, exit polls indicate that only 19% of individual voters in House elections split their ballot in this manner. The number of House districts with split votes is the second smallest number since 1952, trumped only by the lowest number that occurred four years earlier, in 2004, when only 59 districts (14%) split their vote as Bush won reelection along with a 232-member House Republican majority. In short, the two most recent presidential elections have returned the smallest number of split districts in the last half century of national elections. Put another way, there is a dwindling number of districts in which a House representative has any incentive to work with a president of the opposing party.

To quote the well- known political scientist Gertrude Stein, when it comes to the moderate middle in Congress, “There is no there, there.”

In the next several posts I will present more data developing this basic point: voters may wish for bipartisanship in the abstract, but the signals they send in specific elections often belie that wish. We may decry the lack of bipartisanship in national politics today. But the cure means reducing, if not eliminating, the ability of members of Congress to represent their constituents’ interests, as indicated in their votes. In opposing Obama on many domestic issues, Republicans aren’t being obstructionist – they are being effective representatives, just as Democrats believed they were representing their districts when they used the threat of filibusters to bring Senate consideration of Bush’s judicial nominees to a grinding halt when Democrats were in the minority.

This is not to say that bipartisanship will never occur during Obama’s presidency. In fact, we have already seen signs of it, contrary to what the pundits who claim Republicans will never support Obama would have you believe. I will develop this point in greater detail in another post, but in the areas of prisoner rendition, surveillance techniques, troop levels in Iraq and the strategy in Afghanistan, Obama’s choices have been largely consistent with Bush’s, and have attracted broad Republican support even at the risk of offending the Far Left of the Democratic Party. The reason, of course, is that voters in Republican-represented districts largely support Obama’s initiatives in these areas. But it is also the case that Obama has a bit more freedom to maneuver in these areas, because – as yet – they involve actions that do not require a congressional vote.

Can Obama govern in bipartisan fashion? Yes – but only when Republicans believe their constituents will support Obama’s policies, and Democrats do not oppose such initiatives. For reasons I have described in multiple posts, the incentives for members of Congress in both parties to do so have declined in recent years.

It is easy for pundits to blame the lack of bipartisanship on Republican obstructionism. But it is also wrong. Republicans, as Democrats did when Bush was president, are for the most part simply responding to the political incentives set in motion by the Framers more than two centuries ago when they established the system of congressional representation and elections.