The sense of disappointment among many progressive pundits yesterday, particularly denizens of the twitterverse, to what they viewed as President Obama’s tepid remarks on the Michael Brown killing was palpable. Rather than attempting to condemn the actions of the white police officer who shot Brown, or to place Brown’s death in the larger context of police shootings of black men and race relations more generally, the President gave a decidedly more measured response, stressing the need to maintain the peace in Ferguson while the facts are gathered. Perhaps the most noteworthy takeaway from the press conference is that he is sending Attorney General Eric Holder to Missouri.

Needless to say, this was not the response many progressives wanted to hear, and they weren’t shy about making their disappointment known, as this sampling from my twitter feed and other sources indicates:

“Barack Obama is either very tired, doesn’t believe a single word he’s saying re: Michael Brown, or both.”

And this:

“The suggestion that My Brother’s Keeper could have helped save Michael Brown is ludicrous to the point of being willfully ignorant.”

And this:

“Barack Hussein Cosby”.

Ouch. And when asked whether he would personally travel to Ferguson, instead of a dramatic version of Eisenhower’s “I shall go to Korea” the president was noncommittal, prompting twitter responses like this:

“Even Bush didn’t take this long to get down to Katrina. Jesus.”

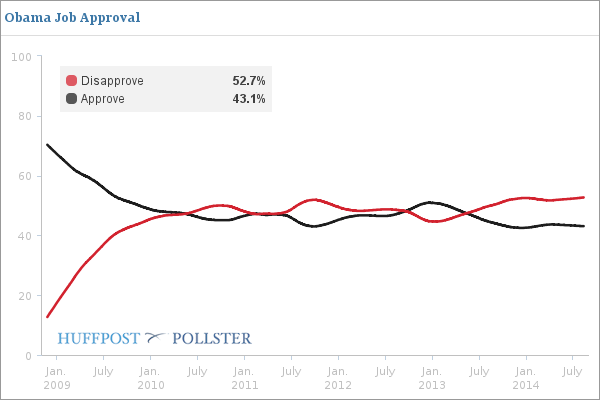

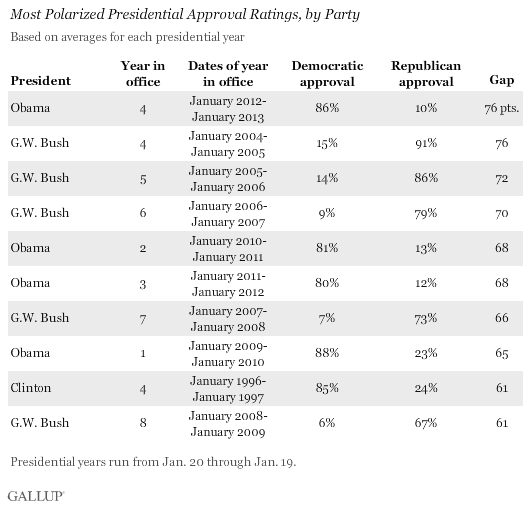

In trying to explain the President’s failure to take a more strident stand, some progressives defended him by suggesting he was likely hiding his true views in order to avoid inflaming an already unstable situation. Ezra Klein’s take is not uncharacteristic of this perspective: “The problem is the White House no longer believes Obama can bridge divides. They believe — with good reason — that he widens them. They learned this early in his presidency, when Obama said that the police had ‘acted stupidly’ when they arrested Harvard University professor Skip Gates on the porch of his own home. The backlash was fierce.”

Maybe. But here’s a radical thought. Perhaps there’s another explanation for the President’s muted response – one that is admittedly more outlandish than what progressive pundits would have us believe: it’s that the President actually meant what he said yesterday. Maybe – just maybe – he really does want to wait until all the facts are in, rather than following the Twitterverse into a headlong rush to judgment. Maybe he understands that the circumstances surrounding this incident may not be as black and white as the armchair analysts twitting their views from their computers thousands of miles from the scene of the shooting would have one think. Maybe he sincerely believes that the best way to defuse the tension is to let the investigation run its course, rather than trying to force facts and rumors of facts into a pre-existing framework of analysis designed to confirm what some pundits are certain happened.

Shocking, I know. But, as I have argued from day one of Obama’s time in office, this pragmatic, show-me-the-facts – dare I say “moderate”? – take on the presidency is exactly what we – progressives included – should have expected from Obama, based on his prior history. And it is entirely consistent with a President whose operating mantra is captured in the phrase “don’t do stupid things.” Yes, there may yet be a time for the President to reprise his stirring 2004 keynote address at the Democratic National Convention – “There’s not a black America and white America and Latino America and Asian America; there’s the United States of America” – or to echo the theme of racial harmony that characterized his Reverend Wright condemnation speech – “As such, Reverend Wright’s comments were not only wrong but divisive, divisive at a time when we need unity; racially charged at a time when we need to come together to solve a set of monumental problems.” But those speeches were made by a man who dreamed of becoming president and they were, in large part, designed to further that goal. As President, however, Obama no longer has the luxury to be quite so self-indulgent. Yes, there may come the moment when he can use the Michael Brown tragedy as an opportunity to talk about race relations, civil rights, police shootings and the myriad other issues that progressives wish Obama had addressed yesterday. But as President he has evidently concluded that this moment is not now. Some find this disappointing. Others, however, may interpret the President’s reticence as a sign of true leadership.

For notifications of future posts, join me on twitter at @MattDickinson44