It was the best of times. It was the worst of times.

Five months ago, a seemingly dysfunctional Republican Party watched as three of its own members torpedoed a last-ditch effort in the Senate to keep efforts to repeal Obamacare alive. That outcome, highlight by John McCain’s “no” vote in the wee hours of the morning on a so-called “skinny” repeal bill, not only appeared to end Republicans’ seven-year effort to repeal Obama’s signature legislative accomplishment. It also highlighted the inability of the Republican Party to legislate despite holding majorities in both congressional chambers. The failure prompted a furious President Trump, who had made repealing Obamacare a cornerstone of his 2016 presidential campaign, to lash out on twitter at party leaders for “letting the American people down.”

Why did the repeal effort fail? As Kate Reinmuth and I describe in our study (gated) of the failed Republican effort, while Republicans were united on the need to repeal Obamacare, they could not agree on what to put in its place. Moderates like Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) and Susan Collins (R-ME) worried about the impact repeal would have on insurance premiums and on Medicaid recipients in their home states. McCain expressed concern that the House would simply pass the Senate skinny bill, rather than go to conference as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell promised in order to hash out a more comprehensive repeal bill that could pass both chambers. Some Republicans, like Senator Rand Paul (R-KY), worried that the repeal bill did not go far enough. In an era of deeply polarized congressional parties, and with a slim 4-vote margin in the Senate, Republicans could not afford more than two Senate defections. They ended up with three. However, even if the “skinny” bill has squeaked through the Senate, we argue that it was still very unlikely that a more complete repeal bill would have made it through Congress, given the lack of Republican consensus on what to do after repeal.

Today, that same “dysfunctional” party is poised to pass the most sweeping tax reform bill in three decades, one that promises to roll back taxes for almost everyone – at least in the short term – and, not incidentally, essentially removes the individual insurance mandate that is a cornerstone of Obamacare and which could hasten its demise. The Senate passed the bill early Wednesday morning on a straight party vote, 51-48 (with McCain sitting out the vote as he recuperates at home from cancer treatment.) An earlier version passed the House, 227-203, with only 12 Republicans – along with every Democrat – voting no. Due to the removal in the Senate of three provisions that violated Senate parliamentary procedure, the House will need to revote on the tax measure, but passage appears to be a formality at this point, and it is all but certain that President Trump will sign this tax bill into law before Christmas.

What explains the turnabout, particularly since according to the Congressional Budget Office projections the tax bill will impact the health insurance market in ways similar to that of the earlier repeal effort? In part, it reflects the Republican Party’s ability to make side payments on the tax bill to potentially wavering senators, including Murkowski and Collins, in order to earn their votes. The tax bill contains a provision that opens up Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) to oil and gas drilling – something Murkowski has sought for a number of years. Collins received promises from the Party leadership that they would take up two bills designed to stabilize the health insurance market in the wake of the elimination of penalties for not buying health insurance. McCain backed the tax reform bill in part for what he saw as a return to some semblance of “regular order” in the Senate, although Democrats and other critics will certainly take issue with that characterization of the tax reform process.

But there is a more fundamental reason why tax legislation passed while the repeal effort failed: cutting taxes embodies a long-held fundamental principle of the Republican Party, one to which almost all Republican congressional members express fealty. Commitment to that principle was strong enough to override concerns some had expressed during the earlier repeal effort regarding the impact of gutting the individual mandate. As such, it is a reminder that the members of both parties are, first and foremost, partisan ideologues who are strongly committed to their party’s basic tenets. For all the media talk about satiating party donors, or catering to the rich, the reality is that for Republicans, cutting taxes is as fundamental to their partisan identity as it is for New Englanders to root for the Red Sox. It is part of their genetic heritage. If you can’t support tax cuts, it’s hard to understand why you call yourself a member of the Republican Party in Congress.

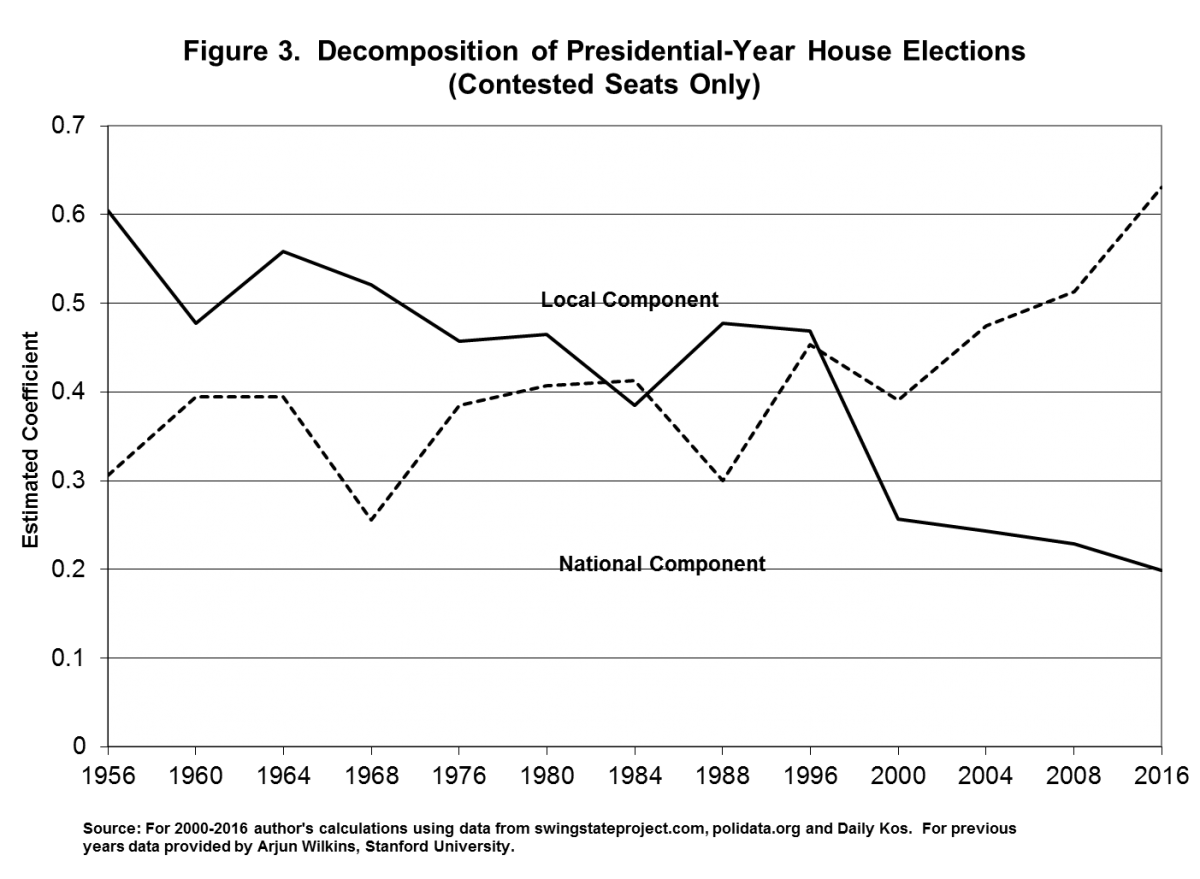

Moreover, despite claims that the tax bill is unpopular, Republicans believe that in an era of deeply polarized parties that are relatively evenly-matched at the national level, it is in their electoral interest to vote together to act in support of party principles, including tax cuts, and to prevent the other Party from reaching its legislative objectives. In this regard, it is worth remembering that the 2016 election was the most nationalized in at least six decades. By nationalized, I mean that the electoral fortunes of Representatives and Senators are increasingly linked to constituents’ willingness to credit or blame the political parties as a whole for the state of the nation, rather than simply voting on the basis of their individual legislator’s record. One way to estimate the relative influence of national versus local forces is to regress the outcome of the House vote in any given election on the previous House vote and on the most recent presidential vote in that House district, while controlling for incumbency and district partisanship. The coefficients on the House variable serve as a proxy for local influences, and the one on the presidential variable captures national tides. Drawing on data gathered by a number of my research assistants over the years, I have been using this approach to document the relative growth in the nationalization of House elections dating back to 1952. As the chart below indicates, elections have become increasingly nationalized since the mid-1980’s, and in 2016 the House experienced the most nationalized elections yet measured for a presidential election year.

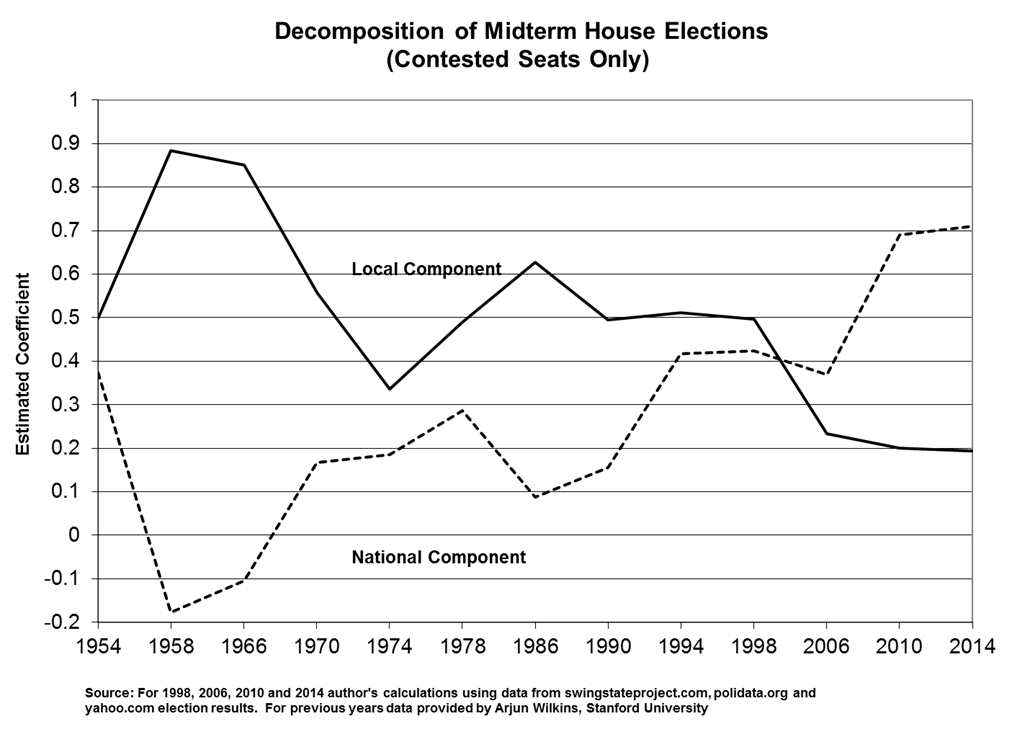

As the next chart shows, there is a similar trend in House midterm elections: an increase in nationalization dating back to the 1980’s, with 2014 showing the highest rate of nationalization to date.

Although detecting similar trends in Senate races is more difficult because there are fewer of them and because Senate cohorts are elected at different intervals, there is some evidence, such as the decline in states that split their Senate contingent between two parties, to suggest that Senate elections have become more nationalized as well. Consistent with this claim, in 2016, for the first time since the Senate was elected through a popular vote, every state that elected a Republican candidate for Senate also voted for the Republican presidential candidate, and every state that elected a Democratic Senate candidate voted for the Democratic presidential standard bearer. In short, there is no reason to believe that Senate races are any less susceptible to the forces driving nationalization.

Although detecting similar trends in Senate races is more difficult because there are fewer of them and because Senate cohorts are elected at different intervals, there is some evidence, such as the decline in states that split their Senate contingent between two parties, to suggest that Senate elections have become more nationalized as well. Consistent with this claim, in 2016, for the first time since the Senate was elected through a popular vote, every state that elected a Republican candidate for Senate also voted for the Republican presidential candidate, and every state that elected a Democratic Senate candidate voted for the Democratic presidential standard bearer. In short, there is no reason to believe that Senate races are any less susceptible to the forces driving nationalization.

But won’t Republicans pay an electoral price in 2018 for backing an unpopular tax bill? Perhaps. But it is worth remembering that for many Republicans occupying relatively safe seats, the bigger perceived electoral threat is not from their Democratic opponent in the general election – it is from partisan ideologues within their own party who often mount primary challenges backed financially by small donors occupying the party’s ideological extremes. In this regard it is worth noting that so far, polling suggests the bill is viewed more favorably by Republican voters, with more than 70% expressing support for the legislation in a recent Monmouth survey. Moreover, as tax bills are increasingly passed on an almost straight party line process, it is also true that they seem to be less popular. For Republicans, the hope is that much of the current opposition to the tax bill reflects the public’s distaste with the partisan nature of the legislative process, as opposed to the details of the tax bill itself. If they are wrong, however, they may suffer an electoral backlash in the 2018 midterm similar to what Democrats experienced in the 2010 midterms after passing an economic stimulus bill and Obamcare on almost mirror image straight party-line votes.

As the cable news talking heads engage in their (usually ill-informed) post tax reform punditry, it is worth recalling the words of another, more astute political analyst: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way…”

And, in the Spirit of Dickens – and of the Season, I give the last word to Tiny Tim!

Only one small quibble (and not one that addresses any key part of the argument):

The two promises made to Collins, regarding mandated CSR payments and the provision of a reinsurance program, address long-standing weaknesses of the current system, things that would have been passed years ago in a more conventional Congress. They’re not designed to address the new blow of eliminating the individual mandate.

Scott – It’s not clear to me that this is what Collins believes – I think she justifies her vote supporting the tax bill in part on the belief that these two pieces of legislation will alleviate some of the hardship created by the repeal of the mandate penalty. Whether she’s right is perhaps another matter. See http://talkingpointsmemo.com/dc/collins-individual-mandate-tax-bill-reinsurance-alexander-murray

Yes, I meant that I don’t think the Collins bills would have the effect of countering the damage of repealing the individual mandate. Whether she believes they will, I can’t say. She may just be searching for some way to justify her vote, or not. It does undermine my image of her as one of the more reasonable Republicans (and a fellow St. Lawrence U alum, too!), but in any event it’s probably hard to be the only Republican to vote against tax cuts.

Yes, and she’s clearly aware that her reputation is taking a hit for her decision to support the tax bill, which includes repealing the individual mandate penalty, when just a few months ago she rebelled against a bill that would have done essentially the same thing regarding the mandate. As best I can tell from her post-tax bill comments, she was never keen on the mandate in the first place as a matter of political principle, and as long as she believes (correctly or not) that she can ameliorate some of the impact of its repeal, she’s willing to do so in the name of tax cuts.

Hi Matt – hope you’ve been well and thanks for a fresh posting!

What do you see as the key drivers for why constituents are evaluating legislators based on national v. individual merit?

Without any proof, I’d imagine variety of and ease of access to media has played a sizable role. Most of the primary internet sources greatly over-index on top level national news/trends (which naturally opens them to a broader audience and more $$).

I rarely see my reps in the news and actively need to seek out info in order to see where the do(or don’t) differ with the party at large – an effort I can understandably see folks forgoing.

Hi Charlie,

Yes, it has been a while. But I needed a break from grading Bureaucracy papers! As for your question, I think there are several causes:

1. The parties have become better sorted. By that I mean the Democratic Party has become uniformly liberal, and the Republican Party uniformly conservative. This means there are very few conservative Democrats (hello Joe Manchin!) or liberal Republicans (where have you gone, Nelson Rockefeller?). As a result, party labels – whether a candidate is a Republican or a Democrat – matter a lot more now, and people are more likely to vote a straight party ticket. That means both parties’ electoral fortunes hinge much more on voting together as a unified bloc.

2. Campaign finance reforms have made it easier for extremists in both parties to contribute money to elections anywhere in the country – and these small donors typically give money to the more extreme candidates. So it means one’s electoral fortunes hinge a lot more on getting campaign contributions from outside the district.

3. The candidates themselves are more partisan in both parties – politics increasingly attracts more extreme candidates in the first place who often become attracted to politics because of a single issue. Think Carol Maloney and gun control.

4. The issues being debated are no longer simply about material concerns – they involve a host of other non-material concerns, such as gay rights, gun control, abortion, affirmative action in schools, etc., in which it is difficult to find a compromise positions. So activists on each side see it in their interest to band to make it appear that every vote is us or them, and it is crucial to defeat the other side.

5. However, you raise a great point, one that I hadn’t really considered. It is possible that social media is contributing as well by “nationalizing” the discussion of issues. But I do wonder how much of the coverage is driven by these other factors – that is, the media is (more or less) accurately conveying what is happening in terms of these other factors, which collectively have contributed to the nationalization of political discourse.

Those are my immediate thoughts. There’s probably other factors at play as well, however.