Games and I go wayyyyy back– enough to necessitate italics and elongated y’s. I think a lot of gamers my age can trace their roots back to watching an older sibling play Donkey Kong Country for the SNES, or maybe Super Mario World 3– sitting there as a little 6 or 7 year old whelp and just feeling totally fucking rad. Nothing was more rad than watching (occasionally playing!) a really cool game with your bro, because the whole thing just kind of made you feel de facto cool by association. Or maybe playing Mario Kart 64 and trying to pop each other’s balloons on the Double Decker stage was like, the zenith of fraternal bonding for you and your siblings because it allowed you to bond in a way that didn’t involve wonky child-like shenanigans. I remember watching my older brothers play Mortal Kombat even though my parents had strictly forbidden it due to extreme gore and photo-realistic decapitations (!!) — but being my siblings, they didn’t really care– in part due to the fact that they were teenagers and didn’t give a flying fuck about the rules, and partly because maybe it was kind of fun to have a bonding experience with their ‘lil bro when the age difference had so often kept us from really getting close.

Like I said, a lot of my early gaming experiences involved watching. My brothers were just old enough and just distant enough to leave me in a perpetual state of affection-vying, which looking back, I think only served to bump-up the dial on my bothersome factor by a solid 8. The more they spurned me, the harder I tried. In retrospect, surviving those teenage years really wasn’t as much of a fucking task as everyone made it out to be, and so I sometimes wrestle with the idea of inquiring about their apparent drug use during that time. Because you know, teenagers love drugs. I don’t know–I can only really describe my relationship with them as a delirious merry-go-round of unpredictable shit, so there’s that bit of evidence. Sometimes I got to watch whole segments of Final Fantasy VII (Cloud’s sword was hnnnngggg) and Final Fantasy Tactics, and other times I was getting yelled at and literally tossed from the room. Maybe they just wanted some privacy to masturbate. Funny — lucidity kicks in around college, suddenly it makes sense.

I kid, I kid.

But the feelings of it all: the sheer breathless excitement of watching my brothers play these extraordinarily cool and grown-up games stuck with me and shaped me in a huge way. For one, I still feel inordinately comfortable watching other people play video games. I’ve had to cut myself off from Let’s Play’s (terrible Let’s Play’s, mind you. Guys, it’s a fucking problem) because I’m actually semi-interested in playing the game and I’ll just watch it mindlessly for hours. I think it’s just a Pavlov thing, like a trigger– me, being the well-trained Mama bird that can instinctively vomit on cue for the sake of mah babies. It just takes me to a comfortable place. This is actually a huge part of why I want to do what I’m kind of currently doing — I grew close to games as a watcher and not as a player. First instinct stuff, like ducks or puppies. I was imprinted to appreciate them in a different way from the get-go, inadvertently shaping the way I approach games to this day (Right? Puppies imprint, right? No fuck. Fuck! What am I thinking?)

Because when other kids wanted to be firemen, or veterinarians, or other stereotypical career paths— I wanted to make video games. Like, earliest aspirations here kind of stuff. It sort of tickled me to think that there are people out there who make these things for a living– these things being the reverent, interactive objects that I loved so much, that allowed me any sort of semblance of a relationship with my bros. Even as a kid, I figured– someone’s gotta make this shit with their bare hands, so why can’t it be me, fuck god damn? I started to grow somewhat impatient with games, watching them as I did; naively, perhaps even hubristically, I thought of ways I could make them better. Paying close attention to dumb oddities and oversights. I grew to appreciate when games did things well and concomitantly ever frustrated with games that just dropped the fucking ball.

Still, I spent a majority of my early years not playing video games and just sort of absorbing them like some wayward jellyfish of the digital ocean, and it wasn’t until much later that I jumped into the realm of playing and being a player, despite the few odd moments here and there (Like that time I was allowed to play Super Mario RPG for a brief period of time: my brothers were shocked to learn that I could hold down the requisite buttons that allowed Mario to run instead of just ambling everywhere. Like, mind blown). It’s all a bit of a blur, mind you, but I remember getting my hands on the Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, and probably Super Mario 64 after my brother Jim moved out of the house. The whole thing was a surprisingly non-emotional episode for me, considering my attachment to his effervescent cool-ness. In hindsight, it was actually pretty thoughtful of him to leave some of his game consoles behind for me to play with. But also, I think he was going into the military. Actually, yeah it was definitely the military. Sure, I was Prima guide driven, but god damnit– I finished Ocarina of Time. And then after that I finished Mario too. Holy shit, I was kind of good at this. All of those careful years, ever the silent and mindful watcher, vicariously contributing to my inherently good video game skillz and the ability to follow explicitly written guides. Okay– so I could beat the games, and there was something very independent and freeing about about that, but at some point the experience had secretly and very suddenly become solitary and non-personal, and I don’t think I was prepared for that.

Even as I strayed from the guides, the absence of the shared experience from my gaming excursions as a whole left it feeling task-driven and slightly empty. I finished Ocarina because my brothers had finished it and it made me feel big and grown-up to beat that last boss– but I wasn’t invested in the story or the characters. I even remember getting elementary school fact-slapped while I was attempting to explain the whole Zelda/Sheik thing to a group of friends (I told them that she had been cursed as a child à la Sleeping Beauty) because I was just making up random bullshit– because I didn’t pay any attention to the story because it didn’t fucking matter to me. I can still recall the whole bitter memory of sitting there as this other, slightly tangential fifth-grader sitting just out of the circle, proceeded to slap the stupid out of me in front of all of my friends– the whole wretched thing just simply embedded into my brain as one of the more sobering experiences of my elementary school mind. And it really was. I was no more acutely aware than in that moment that, oh my god, I had just played the entire game incorrectly. I missed out on something huge, and in fact, was I just making stuff up back there? I’m like–all at once looking at myself in the mirror, this fifth-grade me, wondering how it is I could miss something that big and not even realize it.

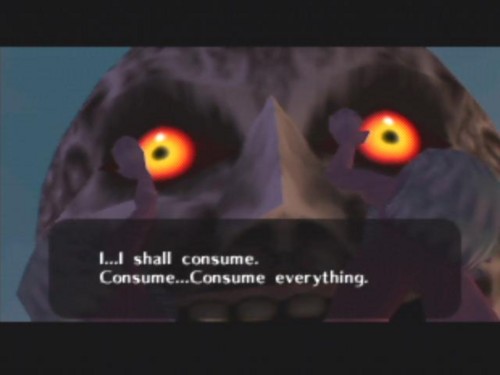

It’s because I was dumb. That’s the short answer, actually– I was a bumbling baby trying to make it in this wide, wide world. I did with the story as I did with a lot of other stories when I was that age– I’d just make shit up. Reading Harry Potter was balls-hard so I skimmed through it and kind of just made things up when I came across inconsistencies. Leave it to the throes of youth. Eventually I wizened up a little bit and picked up The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask a couple years later; and like many other kids of the time, got creeped out by it and put it down. It was a whole slew of things: the atmosphere, the impending sense of doom, the masks– the transformation sequences that always seemed to remind me of that scene from Jim Carrey’s The Mask that I wasn’t allowed to watch as a kid because it was hair-raising nightmare fuel. But something brought me back, maybe a year or so later and I was able to experience it in a way I hadn’t been able to before. It’s like I had leveled up or something and all those +1 INTs had finally granted me the ability to detect subtlety. Majora’s Mask was influential for me here, not because it was the game that allowed me to enjoy games necessarily, but because it was emblematic of a period of time for me when I actually started to develop as a human being and I wasn’t just this collective amalgam of culture and thoughts that had been especially prepared for me to think and feel. The game just had it all together and working.

First off, you could fucking lose this game, and a lot of hard work if you just didn’t get your shit together– lest we forget to mention the moon, ever-looming above your head, threatening to obliterate your progress. You had to play smart, and you had to play quick. Secondly, the NPC’s acted like actual people with actual lives, and hopes, and dreams, and fears– and that was significant because they had stories you could follow and influence, people they interacted with, emotions and back stories. Suddenly the game is very intimate and intense– you have these relationships that are important to you and no real way to end the cycle but to play the fucking game. You look at some of the other Zelda games in the series, and you just don’t really expect the core theme of the game to be about fear, and guilt, and worry– but it totally fucking is. It’s about the unknown and it’s antithesis: about faith in others and most importantly yourself. And if the masks are a symbol of that faith, then releasing each mask to the Moon Children at the end of the game to receive the Fierce Diety’s Mask (which completely annihilates the final boss, btw) is the culmination of having ‘saved’ Termina by purging the people of their fears– by instilling hope in the seemingly hopeless, terminal land.

The game hit me hard; really and truly, it kind of opened my eyes in terms of what games were capable of doing. I shouldn’t heap all of the praise upon this one title, of course–there were certainly others (here’s looking at you, Shadow of the Colossus). But it really showed me that a video game can be personal. It can be real, and actually quite important. And how many times have I fallen in love with a game because of its music? It’s impeccable design? It’s brilliant writing? Each and every journey, a kind of period of my life. I think that’s the magic of it– and why I’m so hellbent on getting this career path to work for me and my life. It’s because video games can take you places that other mediums can’t.

It’s a good thing, I guess, that I’m taking a college course on that.