Seymour Street

To the southwest of the church begins Seymour Street, laid out in 1799 and incorporated in 1805 as the first leg of the Waltham Turnpike (one of the road-building ventures in which Painter was involved). The turnpike ran down Seymour Street, across the picturesque Pulp Mill Bridge. Down this street can be found the 1891 shingle-style (text with tooltip) a style of architecture popular (especially for domestic and medium-sized buildings) from the late 1870s through the end of the 19th century. It is characterized by dominant roofs and the pervasive use of shingles or shingle-like textures on vertical as well as inclined surfaces. former railroad station and at number 7 the Dudley-Painter House, oldest extant house in Middlebury Village, moved from its original site overlooking the Green in 1802.

28 6 Main Street At the corner of Seymour and Main Streets stands the house built for the Honorable Horatio Seymour in 1816–1817. A Yale graduate of 1797, Seymour came to Middlebury in 1799 and opened his law practice the next year. Postmaster, director of the Vermont State Bank, member of the corporations of Middlebury College and the Addison County Grammar School, instigator and supporter of the female seminary, U. S. Senator from Vermont from 1821–1833, and recipient of an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Yale in 1847, he must be counted one of Middlebury’s leading citizens.

His house was suitably elegant. Set atop a stone terrace with a fine old fence (the last survivor of a series of such fences that once defined house lots around the Green), and a handsome flight of brick steps, it is of brick (painted at an early date to seal its walls from the moisture-induced spalling experienced by many of Middlebury’s first brick buildings), with marble-capped walls and chimneys carried above the roofline and joined across the front and back by fine eave balustrades. (text with tooltip) a row of short pillars topped by a rail The ogival door hood is a unique survivor of several that once graced a series of grand Middlebury houses. The unusually-shaped pilasters that support it are a device to be found as well on a number of particularly interesting early-19th-century fireplaces in town. The interior is notable for many reasons. The attic boasts forty-foot hemlock beams. The original kitchen, in the basement but exposed to the south and west by the slope of its site, retains its four-foot-wide back door and large fireplace with bake oven and laundry vats. The first floor centers about an entry hall with a lovely curving staircase (and a curved door set into its back wall). There are ten fireplaces in the house, fitted with some of the most elaborately decorated mantles in Middlebury. Everywhere there are fine details, such as the paneled window embrasures, decorated door frames, rope mouldings, and cloisonné hardware (this last imported from Russia and added by Seymour’s son-in-law, Philip Battell in the 1880s). The Battells also modernized the plumbing, adding a marble bathroom and a new (upstairs) kitchen. They replaced the small-paned windows with Victorian single sheets of glass and added the Italianate (text with tooltip) referring to one of the picturesque vocabularies drawn upon by builders in the middle quarters of the 19th century. Inspired particularly by Tuscan villas, “Italian” details included heavy cornices, elaborate brackets, towers or belvederes, round arched windows, and heavily plastic moldings facing and brackets under the eaves. The house was then occupied by Philip Battell’s son-in-law, Governor (and subsequently U.S. Senator) John W. Stewart and his family. The Governor’s daughter, Mrs. Charles M. (Jessica Stewart) Swift, donated the house and its furnishings to the community in 1932.

In his History of Middlebury, Samuel Swift recorded: “While building his large and very expensive brick house … [Seymour] expressed to the writer of this notice his regret to lay out so great an expenditure on a house.” It took him two years to pay for it. Through his great-granddaughter’s generosity, Seymour’s expense has become the community’s great gain.

29 Post Office Utilizing the site of the 1837 Brewster commercial building and the village’s 1856 fire house, the Post Office was built in 1932–1933 using WPA funding and labor. Its architect was James A. Wetmore, Supervising Architect of the U.S. Treasury, and consistent with the government’s goal of building regionally appropriate, high quality federal buildings throughout America’s communities, it is in a dignified Georgian (text with tooltip) the high style of eighteenth-century America. It is often characterized by formal symmetry and robust detailing (this latter including doors with transoms but no side lights, quoins, pilasters, and Palladian windows) Revival style. The original cornerstone was installed during 1932, under a Republican administration, and identified Ogden L. Mills as Secretary of the Treasury. By the time the building was completed in 1933, power had shifted to the Democrats, and the original cornerstone was replaced by the present one identifying William H. Woodin as Treasury Secretary.

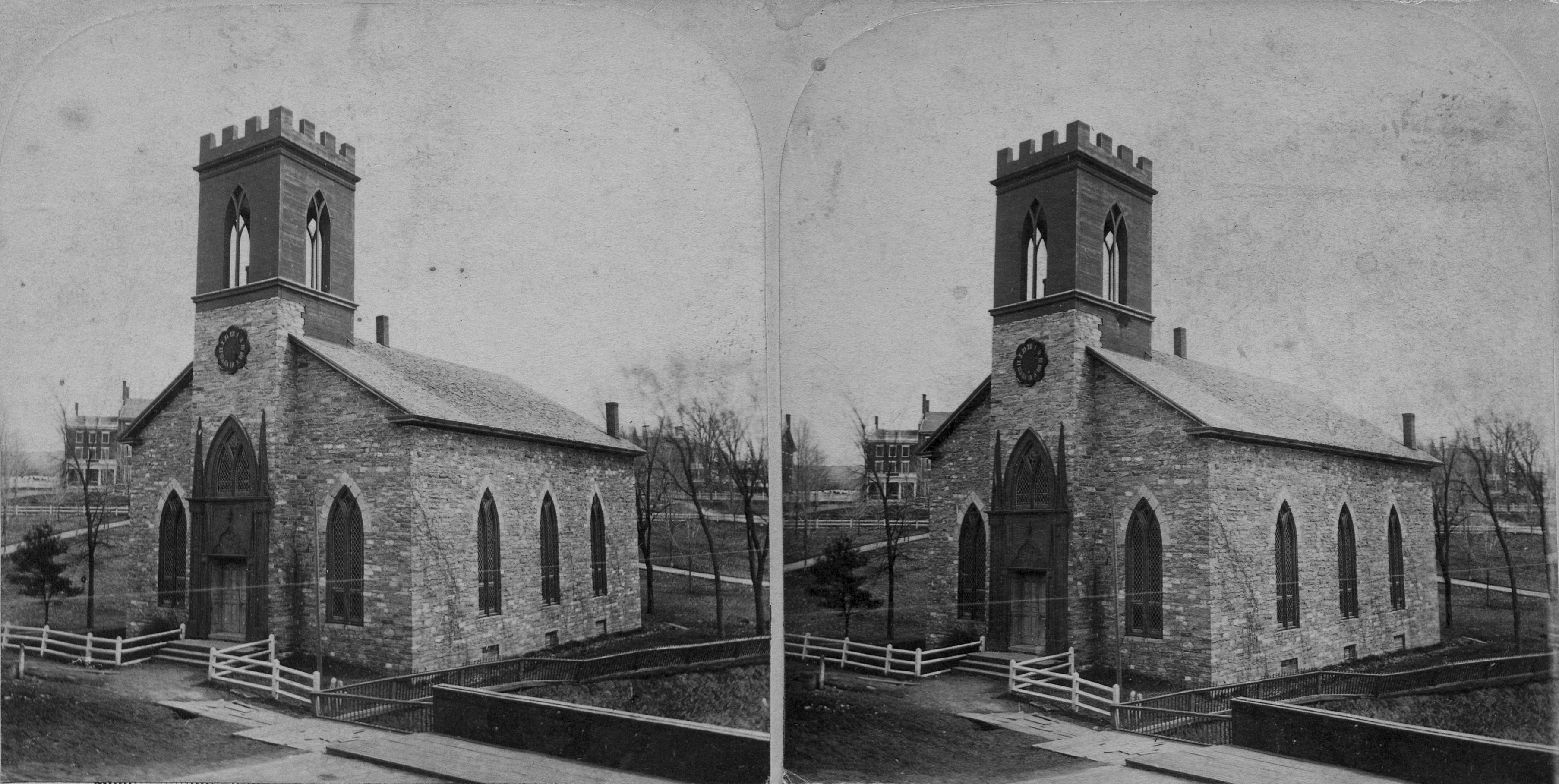

30 St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church The Episcopal Society, first in Addison County, was founded in 1810, counting among its early members Horatio Seymour and Lavius Fillmore. Between 1810 and 1827 the Society met first in the courthouse, then in Seymour’s house, and finally in Osborne House (originally 77 Main Street, now 4 Cross Street). In 1825 the town voted to permit them to construct a church on the Green so long as it was to be of brick or stone (in accord with provisions of Painter’s original deed for the land).

The resultant stone church, the first Gothic Revival (text with tooltip) a style of architecture inspired by the buildings of the later middle ages, typically characterized by steeply-pitched roofs, pointed arches, asymmetrical massing, towers, and applied tracery-derived decoration. It was particularly popular in the United States from the late 1830s through the Civil War for its picturesque qualities and its moral (ecclesiastical) associations church in Vermont, was constructed in 1826–1827. The shell with its pointed windows and western tower was contracted out for $1,600. Its stone was brought from Weybridge, stored on the site of the inn, and wheeled down elevated ramps to the top of the rising walls. The finishing of the interior and the exterior window frames and woodwork appear to have been by Fillmore. Total insured value on completion was $6,000. The choice of the Gothic style for the building at this early date is quite remarkable. (While architects in England had added the style to their working vocabulary by then, it was not until the 1830s and 1840s that it achieved real popularity in the United States.) Its inspiration in Middlebury appears to have been St. John’s Cathedral (1810) in Providence, R.I., and St. Anne’s Church (1824–1825) in Lowell, Mass., the latter of which was cited in an article about Lowell in the Middlebury newspaper as a “handsome new stone Gothic Episcopal Church.” The rector of St. Stephen’s, Benjamin Bosworth Smith, a Brown alumnus who knew St. John’s, was an important proponent for what he considered the only appropriate style for the Protestant Episcopal Church in the U.S. In 1827 in the Middlebury-based Episcopal Register he published an essay advocating for such buildings modelled on “humble English country churches … snug, low Gothic structures with massive walls of rough, unhewn stone, adorned with a few plain windows and a decent humble tower.” Later, as bishop of Kentucky and then presiding national bishop, he furthered the style nation-wide. The detailing around the door, derived from William Paine’s Builder’s Companion (London 1762) includes a pine cone attributed to the Rev. Smith himself.

The original interior was rather more Federal (text with tooltip) a term generally designating the American architecture of the late eighteenth and early 19th centuries and here used with particular reference to the architectural fashion emanating from Boston at this time. It is characterized by planar simplicity and a refined delicacy in proportions and detailing. Decorative details (akin to those of the English Adam style and Wedgewood china) are ancient Roman in their inspiration. Perhaps the most characteristic feature of the style is a doorway composition with a fan light and sidelights than Gothic, with light colored plaster and a shallowly coved (text with tooltip) concavely curved ceiling. At first emphasizing the priority of preaching over liturgy, it had a central pulpit. By mid-century, however, with increasing emphasis on ritual, the pulpit was replaced with an altar and lateral reading desks. In 1835 the tower received its 890 pound bell, purchased from the Revere Foundry in Boston. Stained glass windows replaced plain beginning in 1853; in 1872 the roof and tower were slated; in 1875 a Johnson tracker organ was installed (an instrument on which Henry Sheldon was the long-time organist); in 1876 the whole interior was remodeled with pseudo-structure supporting a false ceiling; and in 1879 a chapel was built. A social space beneath the church was excavated by hand by volunteers in the 1940s and finished in the 1950s. The crenellations (text with tooltip) the battlement-like notches and raised sections of a parapet that originally topped the tower were reconstructed in the 1980s after decades of absence. In 1998 the side chapel was remodeled by Guillot Vivian Viehmann Architects of Burlington as the vestibule to a new office and meeting room wing.

Crossing the railroad tracks on Main Street, one enters the mercantile and manufacturing area that gave early Middlebury its prosperity and vitality.

31 Triangle Park The corner cut off in 1849 from the rest of the Green by the railroad was embellished in 1908 by Joseph Battell and the Century Club with a three-tiered cast iron fountain carried by figures of cranes. Increasingly unpopular because its wind-driven spray would dampen the interiors of open cars parked around it, the fountain was dismantled by the town in 1938 and sold for scrap. Another fountain was placed in the park by the Middlebury Garden Club at the time of the national bicentennial. The fountain urn (from the same foundry and patterns as the larger original fountain) was discovered in the gardens of Battell’s niece, Mrs. Jessica Swift and acquired from her estate. In 2021 it was reset in a redesigned Triangle Park reunited with the rest of the green by the construction of the new railroad tunnel.