INTRODUCTION

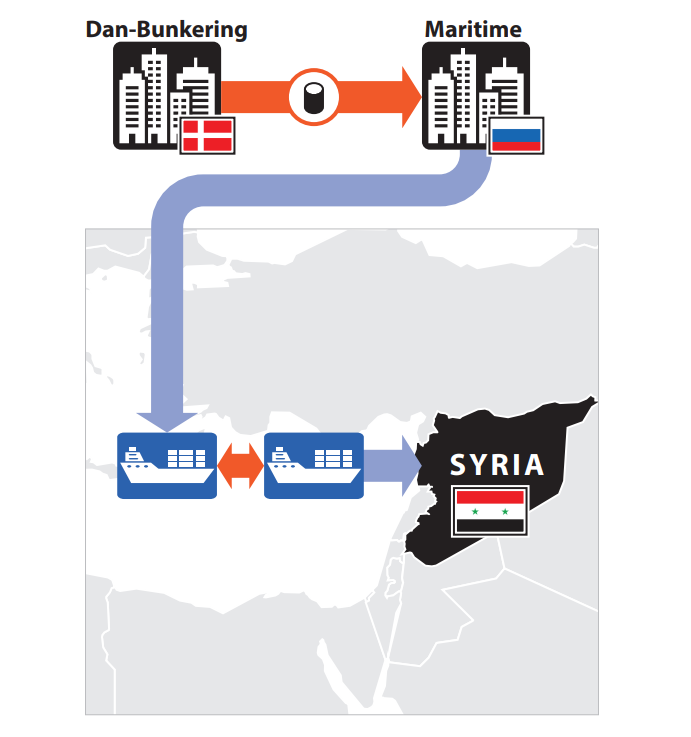

In December 2021, a Danish court fined and convicted the Dan Bunkering shipping firm and its parent company, Bunker Holdings, millions for dollars and gave a four-month suspended prison to the company’s CEO over a European Union sanctions-busting scheme.[1] The company was convicted of selling jet fuel to Russian companies, which in turn transferred the fuel on to Syria in contravention of EU sanctions. The company, which is the largest bunker supplier in the world, is alleged to have made 33 sales of jet fuel worth $102 million between 2015 and 2017.[2]

The case was investigated by Danish authorities from 2016 on, and has attracted significant media and political attention, with serious reputational and financial repercussions for Bunker Holding and Dan-Bunkering.[3] The case rested on questions of negligence and wilful blindness. Did the jet fuel, supplied by Dan Bunkering contributed, even in a small part, to Syria’s civil war? In the words of lead prosecutor Anders Rechendorff, “even negligence can lead to a conviction, and the defendants should have analysed what was going on much more thoroughly”.[4]

In terms of maritime sanctions – it is one of the most high-profile cases of its kind. As a case study, it serves as an example of how lack of effective compliance, particularly with dual use goods, can lead to measurable harm. What lessons can other companies and organizations working with high-risk goods in high-risk environments learn from the Dan Bunkering example?

THE CASE

The European Union, United States, and other jurisdictions have imposed sanctions because of the civil war in Syria. These sanctions include elements that prohibit the supply of military equipment and materials, as well as specific provisions related to the maritime, oil, petroleum, and gas sectors. In December 2014, the EU expressly prohibited the supply of jet fuel to Syria from EU territory, regardless of the fuel’s origin.[5]

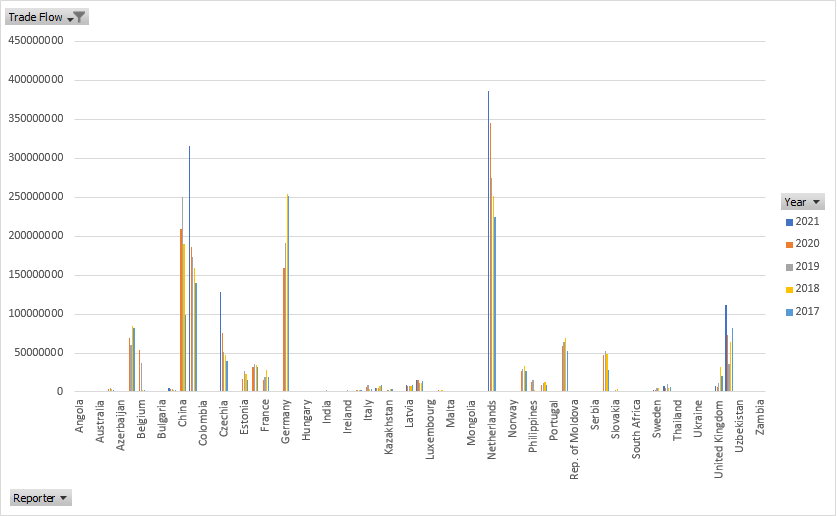

According to press reports from 2016, Russia had been transferring jet fuel to Syria through Cyprus before the EU prohibition. Once the sanctions were enacted, Russian tankers turned to at-sea transfers to avoid entering port. The Dan-Bunkering provision of fuel took place through such ship-to-ship transfers.[6] Reuters reported that such transfers saw a spike in October 2016, one of the deadliest periods of the conflict.[7]

The case was brought to the public’s attention through a series of exposés by the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (DR), drawing significant public and political attention. According to one segment, U.S. authorities had warned Denmark about Dan-Bunkering in 2016; the Danish Business Authority and Dan-Bunkering’s bank, Danske Bank, had also done so. The report by Danske Bank outlined transactions between Dan-Bunkering and a Russian company Maritime; the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirmed that Maritime was supplying jet fuel for Russian fighter jets operating in Syria.[8]

In November 2020, Bunker Holding, Dan Bunkering, and several company executives were charged by Danish prosecutors over these transactions.[9] The case had been under investigation since 2016, attracting significant media and political attention.[10]

GOING BEYOND THE BASICS

Screening against sanctions list is necessary but not sufficient for ensuring compliance and avoiding risk. In a press release following charges being brought in November 2020, Bunker Holding said that its internal investigation “revealed no signs that anyone within Bunker Holding or Dan-Bunkering had any knowledge of the alleged breaches of EU sanctions” and that it had “not supplied fuel to companies included in the EU sanctions list.”[11] Limiting due diligence checks to just screening against sanctions list leaves other relevant information out-of-view.

In addition to screening against sanctions lists, effective KYC (Know Your Customer) – and, ideally, also KYCC (Know Your Customer’s Customer) – due diligence is crucial to accurately assess sanctions risks. The link between the tankers and Russia was known and knowable. Had the company dug deeper into the parties to the transfer, it may have avoided the prolonged investigation and charges being brought against the company and its executives.

Given the operational and material reliance of the Syrian Air Force on foreign support, the risk of diversion to Syrian end users was extremely high. In addition to identifying the end user of cargo, it is also important to ensure that it is not diverted to sanctioned entities or jurisdictions. Contractual clauses requiring proof of the cargo’s final discharge are vital, particularly with goods that could be used for harm, such as in active conflict zones. But so is the knowledge that contracts might not be honoured by all actors, in all circumstances.

It is also key to keep track of events in the press that highlight potential risks. In Autumn 2016, a period in which a substantial number of transfers occurred, the Syrian civil war was one of the leading stories in the global press. An October peak in shipments occurred even after an emergency meeting of the U.N. Security Council and several extremely high-profile events regarding air attacks in Syria were occurring.[12] All this information was readily available on the front pages of major newspapers and reputable online resources at the time.

Violations of the EU Syria sanctions are punishable by a fine or up to four years imprisonment under the Danish Criminal Code, highlighting not only financial and reputational dangers to a company, but also the personal risk to its executives. The prosecution in the Dan Bunkering case sought two years in prison but was ultimately “very satisfied” with the conviction.[13]

CONCLUSION

The Dan Bunkering case is an extreme example of what can go wrong in the world of compliance. Insufficient due diligence led to deep financial and reputational harm to the company. Many a problem could have been avoided by requesting a little more information on end use, foresight of potential reputational issues, and a few cursory google searches.

[1] https://shipandbunker.com/news/world/381571-four-months-suspended-prison-sentence-for-keld-demant-over-dan-bunkering-syria-sanctions-breaches and https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20211214-danish-firms-fined-for-embargo-busting-russia-fuel-sales

[2] ibid

[3] https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news/2159228-bunker-holding-charged-with-breaching-syria-sanctions.

[4] https://news.yahoo.com/danish-firms-fined-embargo-busting-115221733.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAAXLkctj51Iln1TuIFYK4MrNsOS3jfVuqNvGPMI1YyaZoGp-WgDT3CkGTjOvY2PHeHpJwww1uwpWebK_SmwDFXQiYyNMf_RYEJ5Q5MvAoh6M3MYE0Z9w9gTxtpYQgmX-HvjgIfzV5O7VzyjEVAysEoXnMv1n2R_AtRsP1YasweqR

[6] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-fuel-exclusive-idUSKBN13H1T8.

[7] ibid

[8] https://www.dr.dk/nyheder/indland/danish-state-prosecutor-investigates-dan-bunkering-violation-eu-syria-sanctions.

[9] https://www.bunkerspot.com/global/49637-global-dan-bunkering-speaks-out-on-alleged-violation-of-eu-sanctions-against-syria.

[10] https://www.bunkerspot.com/europe/52349-europe-dan-bunkering-court-case-scheduled-for-october

[12] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-aleppo-warcrimes/syria-air-force-bombed-convoy-u-n-says-in-aleppo-probe-idUSKBN1684G0 and https://news.un.org/en/story/2016/09/540932-security-council-un-envoy-appeals-russia-and-us-cooperation-pull-syria-away and https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-fuel-exclusive-idUSKBN13H1T8

[13] https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20211214-danish-firms-fined-for-embargo-busting-russia-fuel-sales