Honoring Mario Cooper, ’77, on World AIDS Day

To mark World AIDS Day we’re sharing this film clip from the 1976 promotional film Middlebury College, a Chance to Grow which profiled Political Science major and student activist Mario Cooper. After graduating in 1977, Cooper went on to earn a law degree and became a key figure in HIV/AIDS advocacy after becoming HIV positive and witnessing the disproportionate effects of the disease in the African American community.

Though it may have once seemed like an unassuming profile of a passionate student, the clip can now be appreciated as an early view into the work of a determined activist who would later become a prominent figure in civil rights and AIDS advocacy movements. The footage and narration also poignantly show Cooper enjoying college life and friendships in a time before the AIDS epidemic changed his life and that of those around him.

Mario Cooper died in 2015 while in hospice care in Washington, D.C. His New York Times obituary can be read here, and a tribute to his work as an activist can be read on POZ, the social network for people living with or affected by HIV/AIDS.

Military tanks move in. At Bread Loaf, 1941

Middlebury’s Bread Loaf campus is usually seen as a peaceful academic retreat nestled in the lush landscape of the Green Mountains, but 75 years ago, it was briefly home to a serious display of military might. College President Paul Moody (who had served in World War I and was a member of the National Guard) hosted the 754th Tank Battalion at the campus in the fall of 1941.

This compilation of footage from 16mm reels in the College archives are believed to show the visit, including a shot of a helmeted President Moody in one of the battalion’s vehicles (an unused title card on another reel in the archives reads: “Prexy Gets Tanked”). Other footage includes author and professor William Hazlett Upson with an unknown child dressed as a soldier, officers visiting the Middlebury Inn, and a procession of military vehicles through campus.

Lieutenant Colonel Robert J. Wallace thanked President Moody in a letter saying, “The quarters afforded us were excellent, and the party held for the Battalion at Bread Loaf by the girls of Middlebury College, will long be very pleasantly remembered by all the men of the Battalion.”

For more information or for permission to use this clip contact SpecialCollections@middlebury.edu. Compilation from original 16mm films in the Middlebury College Archives.

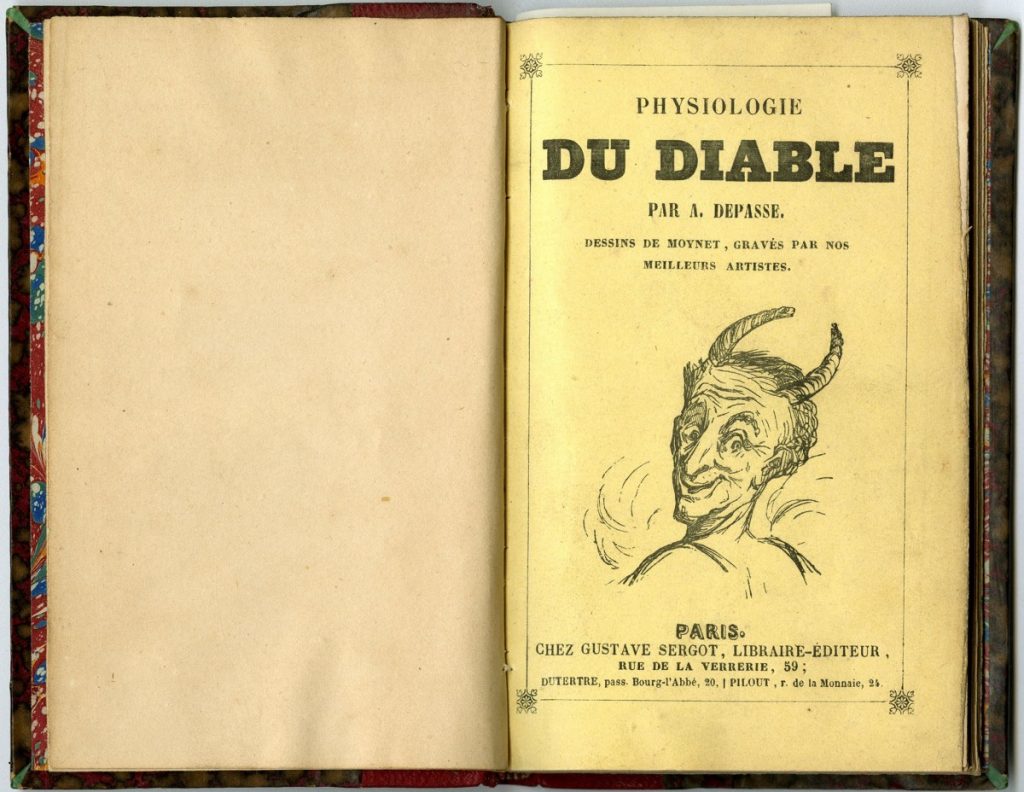

Thinking of French devils, on Halloween

According to this little Parisian book, stored in Special Collections and published in 1842, there are many kinds of devils: the cuckold (diable cornard); the “love devil” (diable amoureux); the wicked devil (méchant diable) and so on. The book, titled Physiologie du diable with drawings by the “best artists” seemed perfect to us for celebrating Halloween. For one, it debunks the idea that only witches ride broomsticks. At least in Paris, in the 19th century, devils took over that role and grabbed hold of the broom. Happy Halloween, from all of our devils to yours.

Physiologie du Diable, 1842

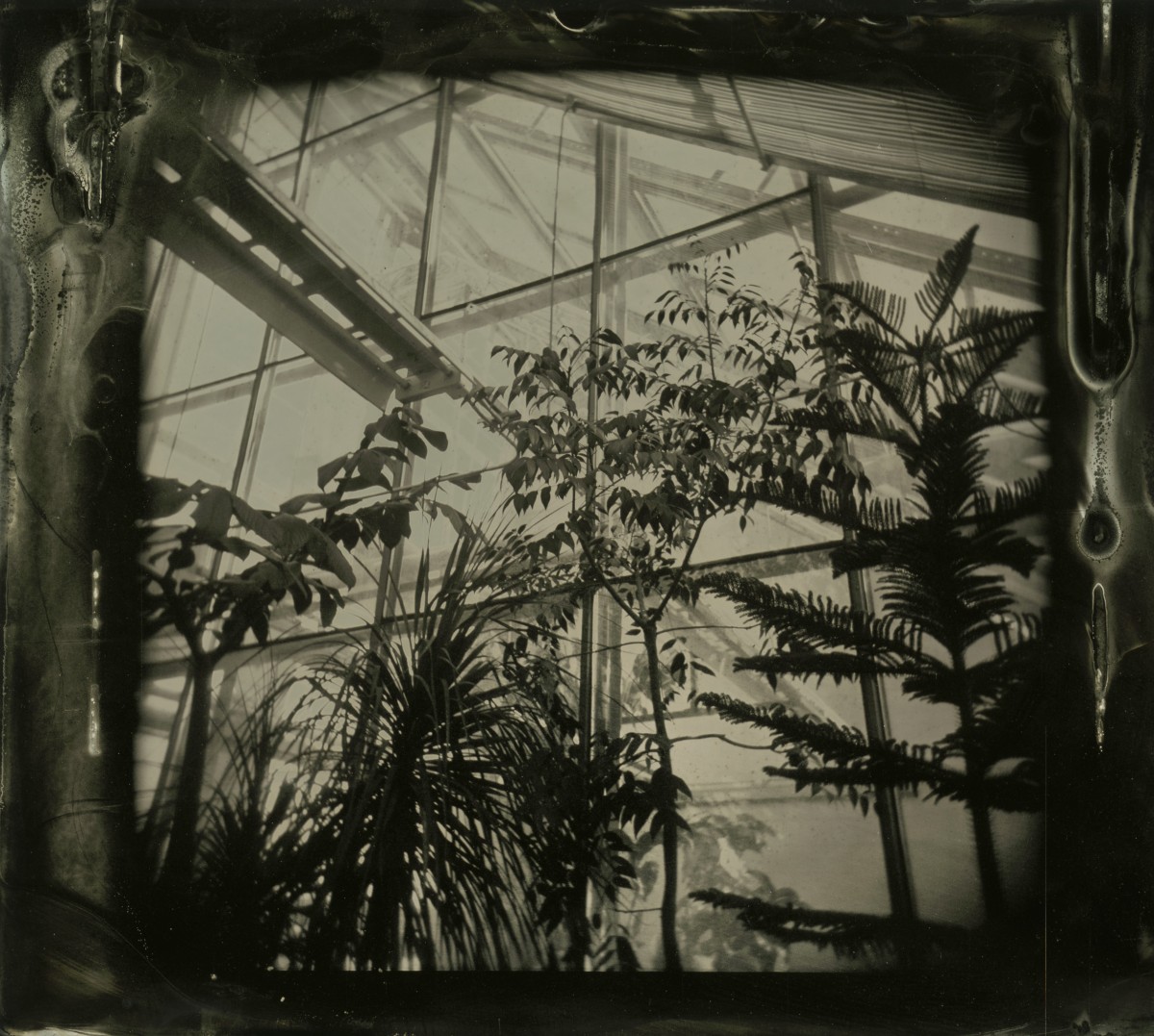

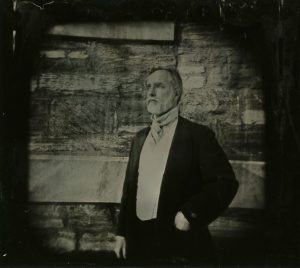

Middlebury Tintypes in the 21st Century

This guest post is by Sam Cartwright, ’18, student employee of Special Collections & Archives.

The early history of photography is filled with laborious, finicky processes as idiosyncratic as the tinkerers who blended art and science to invent them. There’s the daguerreotype, the first and most otherworldly of the bunch which requires viewing its mirrored metal surface at an angle — and developing it with poisonous mercury fumes. There’s the calotype, a painterly reflection of reality imprinted directly onto paper not unlike the cyanotype, a dreamy blue-tinted print. And then there’s wet-plate collodion.

By making a thin layer of collodion (the syrupy result of dissolving guncotton in ether and alcohol) light sensitive then exposing and developing it before it dries, an image can be made onto metal or glass. Early metal plates used in the process were made out of tin, begetting the fitting “tintype” moniker that quickly became a misnomer once iron plates were adopted as a superior substrate.

The wet-plate collodion process was introduced to the world in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer. At the time, Middlebury had just celebrated its semicentennial but was troubled by dire finances, worrisome faculty turnover, and a burnt-out president. One hundred and sixty-five years later (a time with a notably brighter institutional outlook), I began an ongoing project to explore the technical intricacies and unique beauty of the tintype process while here at Middlebury.

Photography was a major part of my creative upbringing and sense of family history; my great-grandmother’s stunning panoramas of the American West adorned the walls of my childhood home and film photography has been one of my main creative outlets since middle school. At the tail end of my first summer away from Middlebury, I took a workshop on the tintype process at the Kimball Art Center in Park City, Utah — a fitting echo of my mother’s experience in that same darkroom learning how to make cyanotypes in her early twenties.

I was immediately hooked and began to plan a wet-plate developing setup here at Middlebury. Thankfully, there was already a student-run darkroom in the Forest Hall basement that was supportive of the endeavor and after a few months of gathering materials, I was able to start putting collodion to plate during my February Break.

Over the course of that week and a few ensuing weekends, I shot a total of 73 plates with my Holga, a simple plastic-lensed camera. Each plate measures 3.5 by 2.5 inches and is made of aluminum trophy metal with a black coating, which is the more affordable modern version of Japan-lacquered iron plates used in the 1800s.

After carefully flowing a mixture of collodion and bromo-iodide salts onto the plates, they were sensitized in silver nitrate. I then had about 15 minutes before the collodion dried, giving me just enough time to fast-walk across the freezing-cold campus to make a 5-15 second exposure. After developing and drying, the final step in the process was to coat each plate with a lavender oil-infused sandarac varnish; warming the plates and varnish over our electric range made my Gifford suite smell like lavender for days — to either the delight or chagrin of my suitemates.

About half the plates depict scenes across campus, my favorite of which are those taken in the Bicentennial Hall greenhouse. The other half are portraits of friends who had just the right amount of curiosity and patience to bear with me as I got used to the process. In the end, my exploration of the tintype proved to be just what I’d hoped: a humbling technical and artistic challenge and a tangible connection to the history of photography. Once armed with a better camera and larger plates, I hope to continue the project.

Peep Shows as Promised!

This post should come as no surprise to our Stacks & Tracks listeners, as our theme for the first episode of the semester was our newly acquired peep shows!

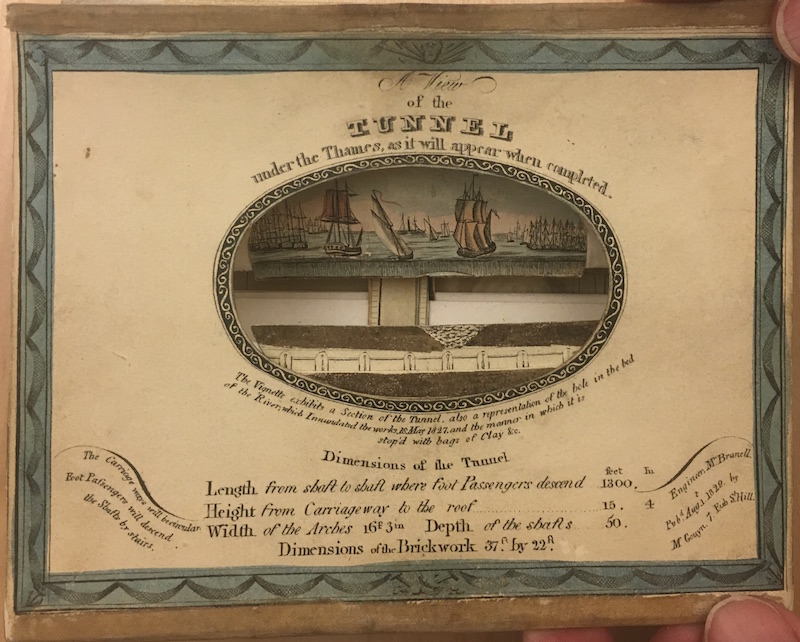

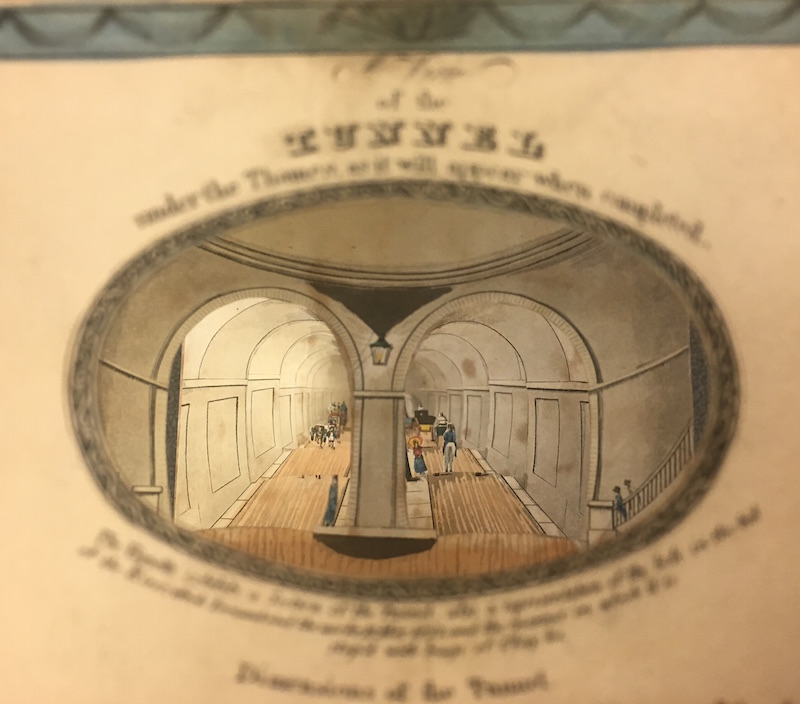

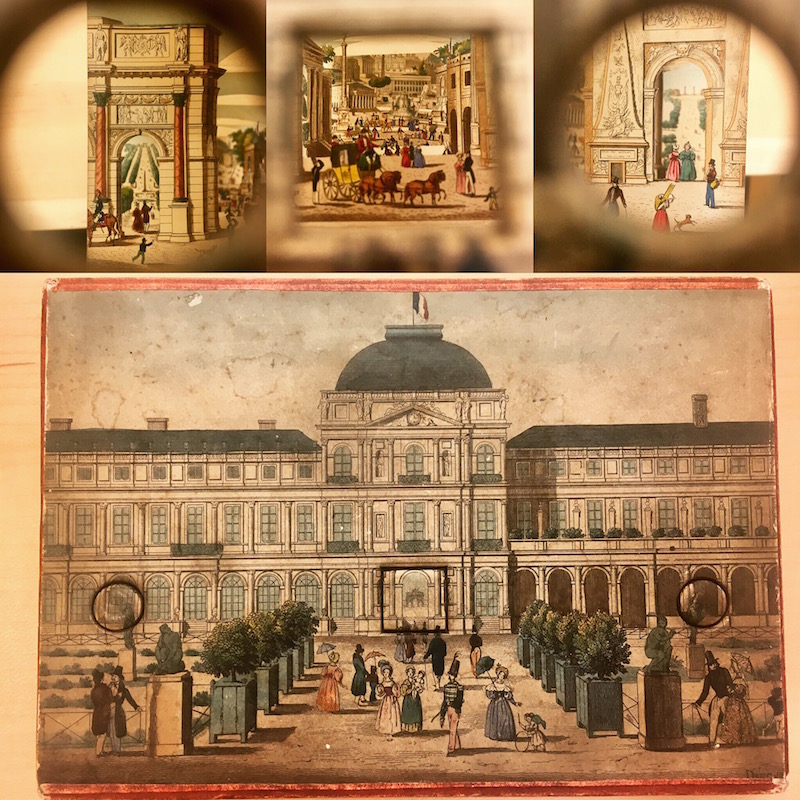

Peep shows burst onto the European scene in the early 19th century with Austrian printer Heinrich Friedrich Müller’s first “Teleorama” in 1825. These tunnel viewers became immensely popular in Germany, Austria, France, and England, and we are now the proud custodians of examples from the latter two countries.

The first, “A view of the tunnel under the Thames as it will appear when completed,” depicts a projected view of the first tunnel under a river ever constructed. This peep show offered a glimpse into the future as it was printed in 1829, and the tunnel was not completed and opened to the public until 1843.

The accordion structures unfold to display perspective views to captivate and entertain audiences.

The second, a French peep show from around 1836 with the Les Tuileries Palace on the front features three viewing options.

Through the center square we see pedestrians, carriages, and equestrians on the streets of Paris, with monuments and churches, fountains and buildings, representing the best of the city.

The left and right cutouts complete the picture with views of gardens.

If you missed today’s show, be sure to listen to WRMC Wednesdays from noon to 1pm. And come peep these peep shows yourself in our reading room from 1-5 Monday through Friday.

RBMS TF238. T47 V54 1829

RBMS DC782. T9 O68 1836

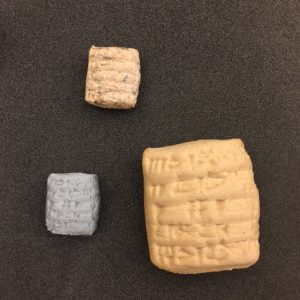

Ancient clay artifact meets the Future

Today in Special Collections, our oldest text faced the library’s newest technology.

Our cuneiform tablet, a beer token from 2,000 BCE, took a new form when DLA postdoctoral fellow Kristy Golubiewski-Davis captured it in a 3D scan.

To see 3D scanning in action – along with the tablet and other important Special Collections objects – come to Davis Family Library this Friday! Kristy will by demonstrating 3D scanning in the library atrium from 10am-2pm, and Special Collections will host our annual Fall Family Weekend Open House from 1pm-4pm.

And stay tuned for a 3D printout made from the scan coming soon, a plastic facsimile students and researchers can inspect in their own hands!

Update 10/7/16: The 3D printouts are here!

Stacks & Tracks, on the radio. Tune in.

Stacks & Tracks.

The Special Collections & Archives radio show.

We’re back.

From the bowels of the library basement come wonders like you’ve never seen. (And still can’t, because it’s radio.)

Wednesdays, 12p-1p

91.1FM | iTunes radio | listen online | on your phoned

Visit us. Monday-Friday, 1-5p. You never need an appointment, or an excuse, to stop by.

Endless Summer in a 1930s Snapshot

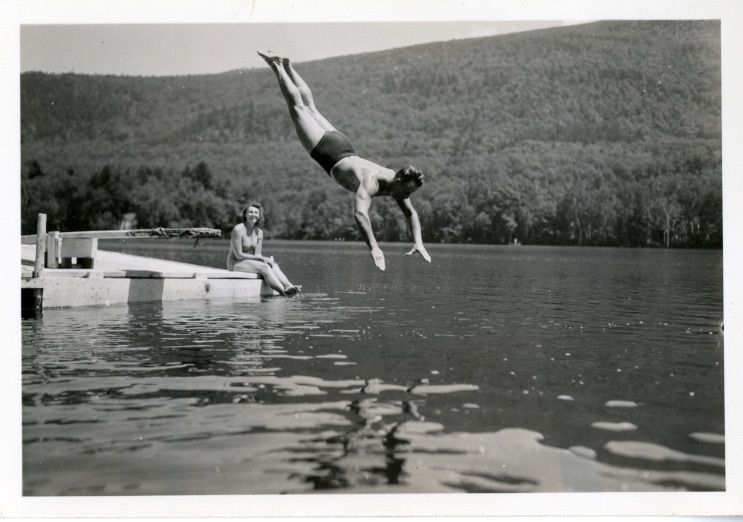

Every day in the archives, we encounter pieces of history that remind us how our world has evolved over the years, and how some things remain the same through the cycle of seasons. For example, this Middlebury College News Bureau photograph from the summer of 1934 could just have easily been shot yesterday on sunny Lake Dunmore.

The idyllic scene is a timeless representation of Vermont summer, and as we bid farewell to another August – welcoming September’s cool mornings and return of students – we dive into autumn, fighting the urge to cling onto the beauty of summer, for we know it will be back again next year.

Get out and vote like it’s 1924!

In honor of the Vermont primary on August 9th, we remember that every vote counts – even in a small town.

The tiny Vermont town of Somerset (which still exists!) could not be silenced despite losing 50% of their voting population in 1924. In one fell swoop, the town clerk, treasurer, tax collector, constable, and school director departed, leaving the other two legal voters the only residents eligible to cast their ballots.

Though the town currently boasts a similarly small population, we hope they, and all voting Vermonters, make it to the polls tomorrow!