When it comes to the time-honored form of the chapbook, the power of literacy comes in small packages.

Such power was on display in the archive last week, when we laid out an array of these bite-sized books for a visit from Karin Gottshall’s Structure of Poetry class. Students in this class compile hand-bound chapbooks of their own work for a final project, so by bringing them into Special Collections, Karin and I hoped to situate their creations in the surprisingly long and storied history of this short form.

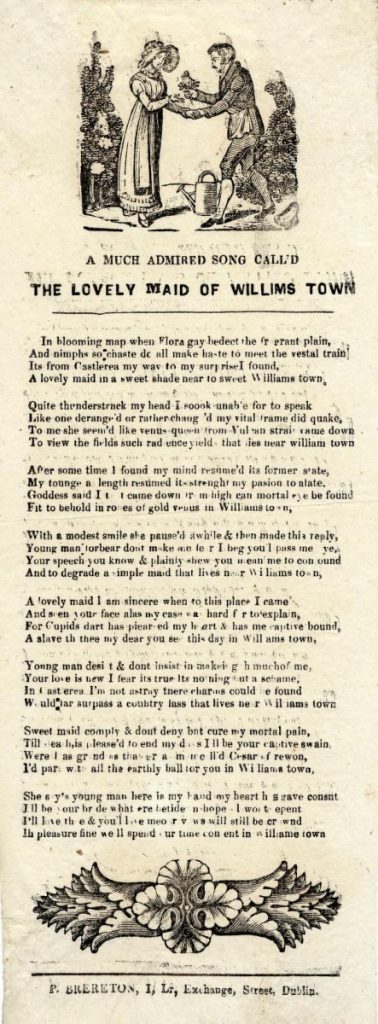

The roots of chapbooks go back to 16th century Europe, when printing technology began to democratize. Books had long been the preserve of the wealthy, who possessed both the education and means necessary to read them. This changed, however, when the increasing accessibility of paper and printing presses made it feasible for unbound books of eight or twelve pages to be sold for a penny or less: in those days, not as negligible a price as it might seem, but still within the reach of a laborer’s wages. Itinerant peddlers called ‘chap-men’ rose to meet this demand, carrying printed matter from presses in the cities to an eager audience of the rural working classes. These early readers thrilled to tales of adventure and roguery. Even those who couldn’t read were able to participate, thanks to the chapbook’s fluid relationship with orality: many early examples came in the form of folk songs, so they were meant to be performed publicly as well as read in private. Early chapbooks also tended to be profusely illustrated, but this wasn’t always an aid to comprehension — because woodcut engravings were so cheap to reproduce, they were often recycled throughout many different texts with little regard for the subject matter.

Chapbooks’ wide accessibility also made them a political force to be reckoned with. Literacy rates burgeoned among the European public in the late 17th century, abetted by the institution of charity schools for educating the poor, but also likely owing to the simple fact that written materials were cheaper and more plentiful than ever before. In any case, whether they merely responded to the demands of an increasingly literate public, or played a part in producing it, the rise of chapbooks accompanied an unprecedented state of affairs: reading was no longer the sole domain of the upper classes.

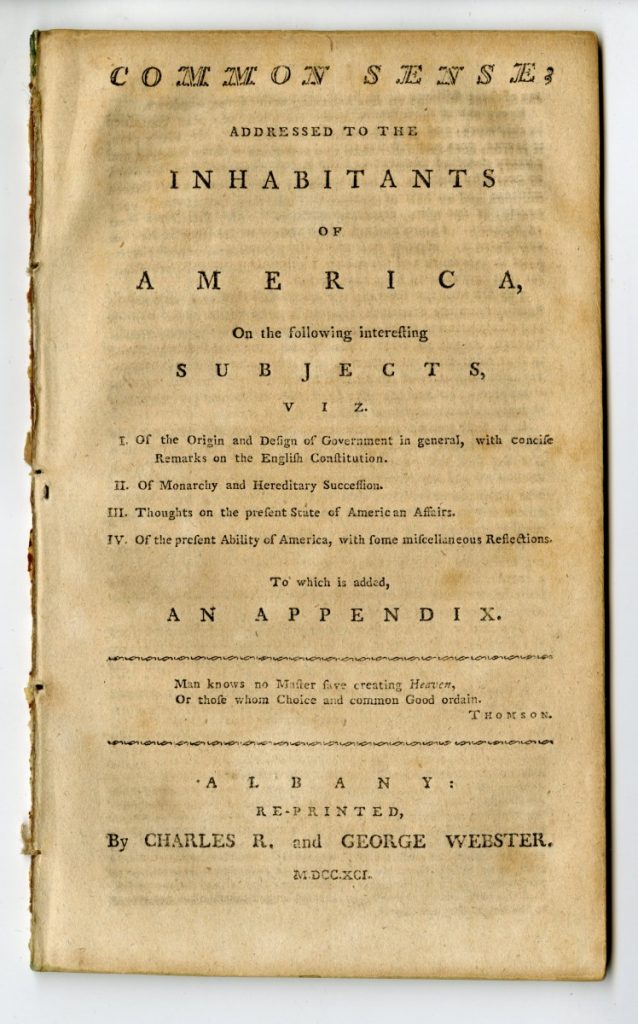

This might not have been so disruptive if the form were restricted to folk tales and ballads, but by the 18th century, some chapbooks began to reflect the Enlightenment mores that were taking society by storm. Examples include Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man, which was copiously reprinted in chapbook form for years after its publication in 1791. The insurrectionary potential of pamphlets like Paine’s, and other radical thinkers, inspired a backlash. While chapbooks had originally sprung up to appeal to their audience’s unstudied interests, relating their stories in an amoral and non-didactic tone, publishers in the 19th century began to prescribe certain interests to their readers for their own good. This led to a proliferation of religious chapbooks, often called ‘Sunday schools’ or ‘godlinesses’, which aimed to bolster the moral fiber of the plebeian masses whom the racier strand of chapbooks had previously entertained.

This sanctimonious turn ushered in a long period of dormancy. Along the way, chapbooks lost their monopoly on the dissemination of cheap print: industrialization reduced the costs of printing once again, allowing lower class readers to lift their sights from the compact octavo or duodecimo bindings of the traditional chapbook towards the sprawling forms of newspapers and novels. By the time the chapbook returned, in the early 20th century, it was to bear the evidence of these radical changes.

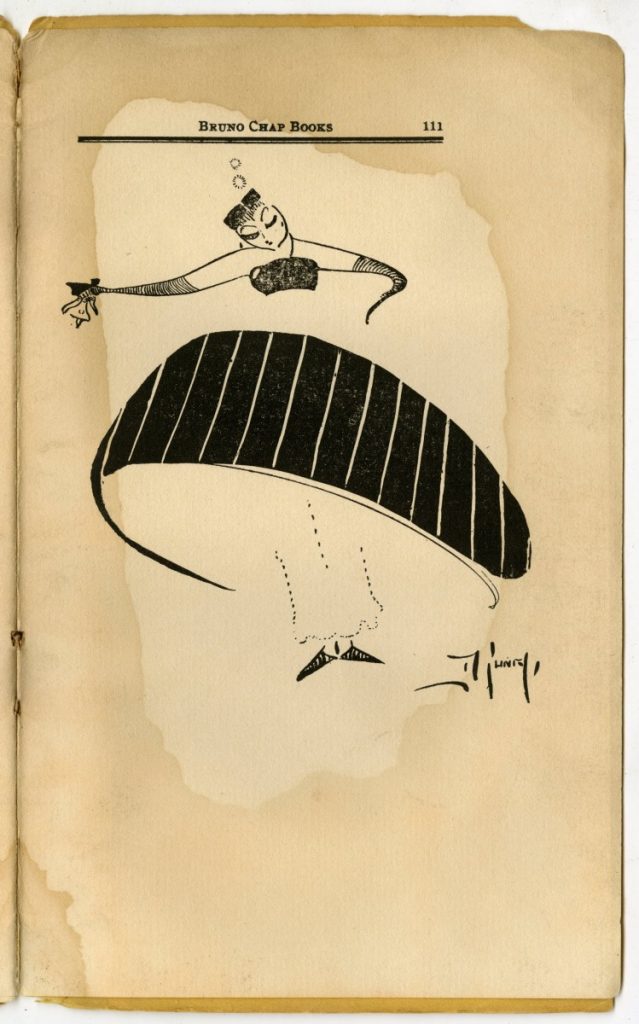

By the time of its resurgence, ‘chapbook’ may have been a conscious archaism hearkening back to a preindustrial past. The printing press enjoyed a rush of renewed interest beginning in the late 19th century, thanks to the Arts and Crafts movement — a group of artists and designers who reacted to what they saw as the garish aesthetic standards of the day by advocating a return to traditional methods of handicraft. Chapbooks, which began their history spurred by the early forerunners of industrial technologies, now arose in protest to the alienation thought to be inherent in mass production. Along with this stylistic shift came a major reorientation in genre: where the chapbooks of yore focused on the episodic and the epic, tales of daring and debauchery, the new artisanal chapbook adopted a lyric mode. Its primary genre was poetry.

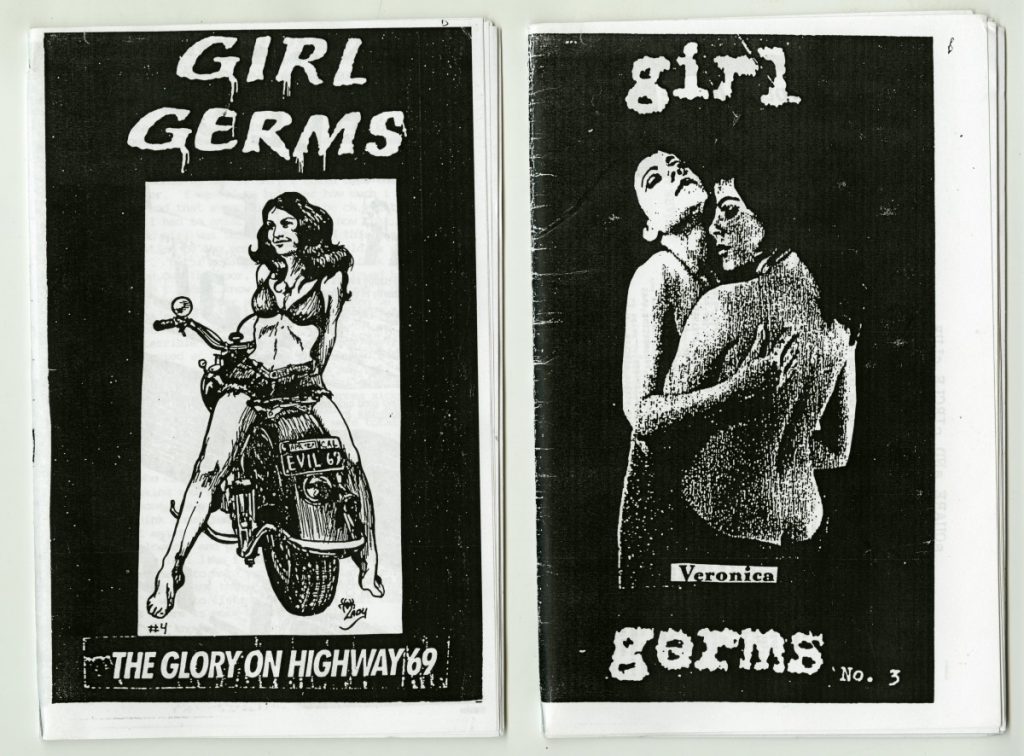

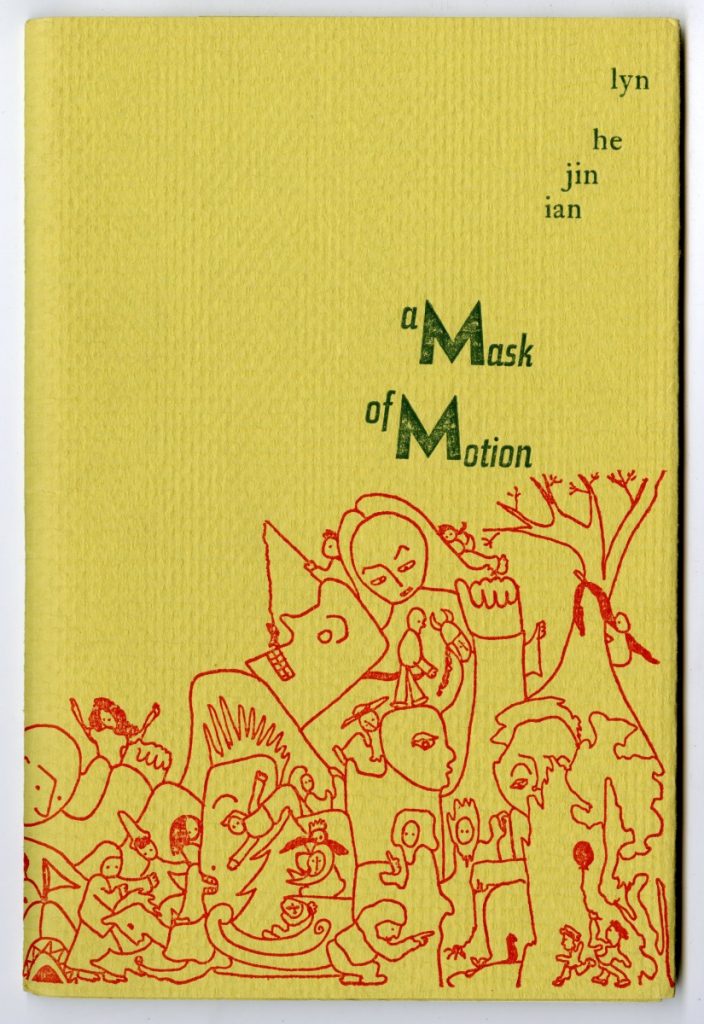

At first this meant the poetry of the early Modernists — writers like Ezra Pound, H.D., T.S. Eliot, and Djuna Barnes — who published short-form leaflets of their work, as well as placing it in collections and literary magazines. It also saw currency with Dadaists in Europe, and in the tracts of the Russian avant-garde. But the chapbook continued to have an ambivalent relationship with the aesthetics and distribution methods of high and low culture. Soon the 20th century brought its own technological changes, in the form of typewriters and mimeograph machines that put the power of textual reproduction more directly in the hands of writers than ever before. These tools were eagerly seized upon by Beat poets of the 1950s. The utilitarian manuscripts they hacked out of their typewriters may seem like a far cry from the nostalgic designs of Arts and Crafts printers like William Morris, but there is some political coherence to this unlikely pedigree. The creators of chapbooks have always been concerned with circumventing the official channels by which writing is allowed to make itself available to a public. Over the course of the 20th century, this labor was to unite authors as disparate as feminist consciousness raising groups and Star Trek fans, as the chapbook morphed into the zine.

But some chapbooks stayed chapbooks, particularly within the domain of small press publishing. Short, artfully designed books remained an appealing form for poets and writers who wanted to reach niche audiences and sidestep corporate publishers. This is the crop of chapbook most abundant in our archive, and it made up the bulk of what Karin’s students saw last week.

Of course, you don’t have to have a press to make a chapbook. The students in CRWR 175 will approach the task armed with nothing more than a word processor and some sewing expertise (and let’s be clear, there’s also no shame in staples). We hope that some of their creations might find their way into our archive to rest alongside their fellows. If you have a little book of your own that’s been hanging out in a drawer for months or years, consider re-homing it in Special Collections!

For further reading, see:

A Pleasant History of the Chapbook

McGill Library’s Chapbook Collection

A Short History of the Short Book