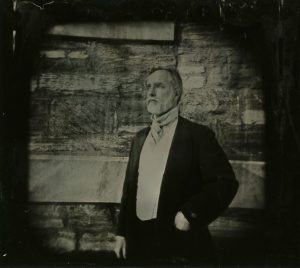

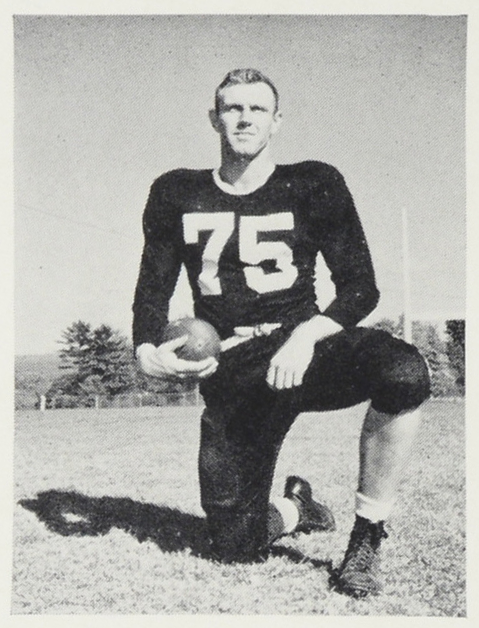

Imagine being the subject of a nationally broadcast television special that profiled your life as a star college athlete. Now imagine that the first time you saw that program was over 60 years after it first aired. That’s what happened to Carey Smith, ’54 when he recently viewed this clip from a newly digitized 16mm film reel in the College archives. Part of an hour-long program originally produced by NBC as an overview of the 1953 season of NCAA football (and in particular, the introduction of the newly instituted one-platoon system), the clip captures Smith’s reflections on the Middlebury experience in a dramatic fashion that only mid-century network television can deliver.

The clip opens with an easygoing overview of the program given by famed NBC personality Dave Garroway who then introduces us to Smith, the captain of the 1953 Middlebury football team, as he arrives early on campus for his senior year. After chatting with coach Duke Nelson, Smith walks across the empty football field and up windswept bleachers where he daydreams about the year ahead: football season, keeping up with classes, and skiing at the Snow Bowl. Finally, in a move that may be familiar to many seniors (this author included), Smith takes a pensive walk up the hill to the Chapel, all the while ruminating on his time at Middlebury and what might come next after that time runs out.

In the end, Garroway asks, “Thirty years from now, what will have happened to Carey Smith?” Unlike viewers in 1953, we know the answer to that question. Smith joined the military after graduation and served in Japan and Korea, eventually finding a career as a school superintendent. College archivist Danielle Rougeau recently spoke with Smith who revealed that because the segment was filmed before the semester started, townspeople filled in to play the other college students (including his supposed love interest, Jean Walters). Although it was screened in his hometown theater, Smith hadn’t seen the film until it was posted on Vimeo and neither had his five children, all of whom were unaware that he had ever played collegiate football.