The Bread Loaf School of English students in Gwyneth Lewis’s Poetry Detective Workshop visited Special Collections on July 26th to study manuscript and printed poetry of several important American poets. Expecting to, as the course description delineates, “use the tools of the sleuth to gain entry into the poetic mind behind individual poems,” the students instead gave the course title a literal meaning when they discovered an exciting and curious paradox…

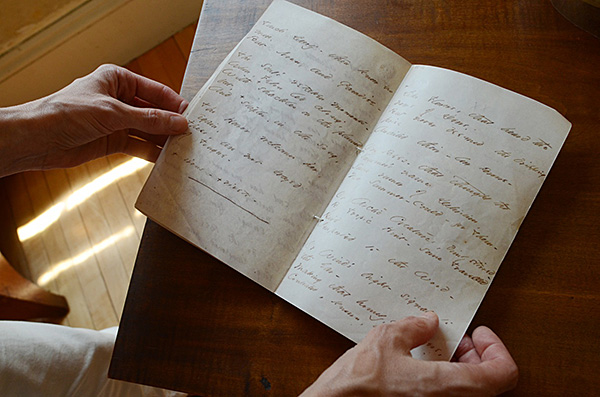

Manuscripts (along with a couple of manuscript facsimiles) and printed editions of American poetry by Robert Frost, Walt Whitman, Langston, Hughes, Julia Dorr, Anne Sexton, and Emily Dickinson were arranged on tables to show the journey from the poet’s mind to the printed page.

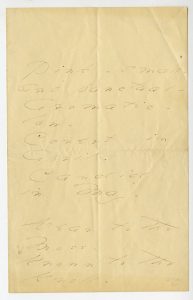

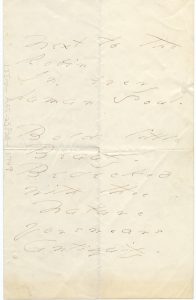

For Emily Dickinson in particular, this transformation warrants investigation. Often described as a recluse, Dickinson was very private with her poetry and altogether averse to having her poems published. Despite spending much time at home in Amherst, Massachusetts, Dickinson was not intellectually or emotionally cloistered. She disseminated her poetry among her friends, sharing her poems in letters, constantly updating and rewriting her poems before collating and binding them in her fascicle booklets – her alternative to publishing them.

After her death, her friends and family set out to publish her works so that her genius might be known to the world. However, determining which variation of her many works best reflected her authorial intent proved a challenge. Dickinson’s first publishers, sister-in-law Susan Dickinson and mentor Thomas Wentworth Higginson, unbound her fascicle booklets and mixed them with the other drafts of her poems in the editing and publishing process. For decades, editions of Dickinson’s poetry hit the shelves with varying structure, both in the poems’ organization in the edition and in poetic structure: editors took liberties naming her poems (Dickinson herself only titled nine), updating her punctuation, and ordering them based on perceived theme or assumed chronology (she did not date her poems).

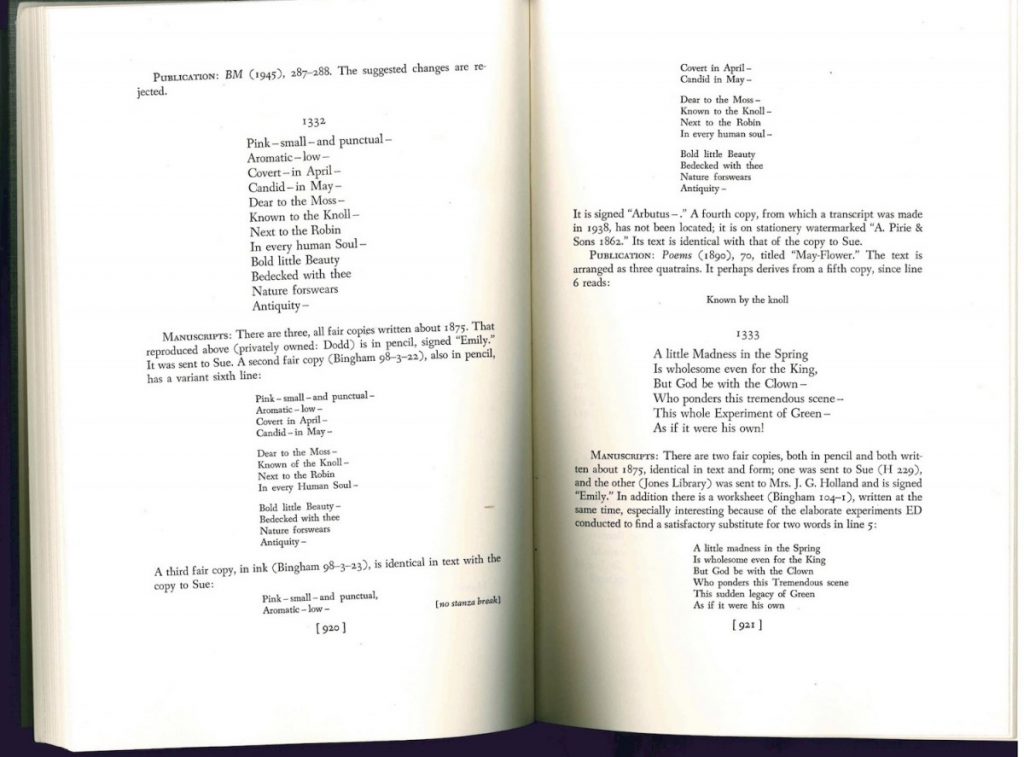

Because Dickinson did not publish her own poems, her manuscripts are paramount in understanding her works. And because she produced so many drafts without a clear final version, comparing the written copies of her poems is the best way to determine her intended meaning. The first to do so was Thomas H. Johnson, who published the first single edition containing all of Dickinson’s poems in 1955. Working from the original manuscripts rather than the dozen published editions of Dickinson’s poems, Johnson described the manuscripts he consulted to provide a more complete view of the poet’s process.

This very edition, the 1955 Johnson variorum, was open next to a manuscript poem for the Bread Loaf “Poetry Detective” students to study.

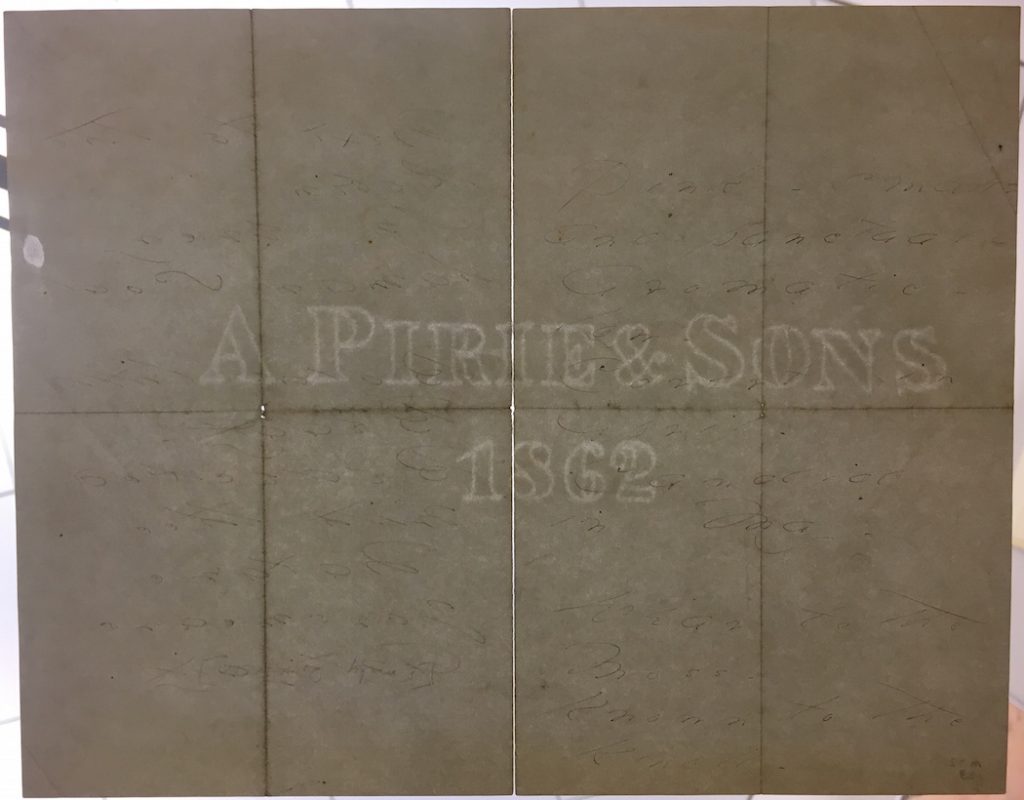

In their investigation, the students turned to the entry which corresponds with the manuscript in question (pictured above) to read Johnson’s description and made a startling discovery. The handwritten poem before them matched a copy that Johnson wrote, “has not been located,” written “on stationery watermarked ‘A. Pirie & Sons 1862.’” They lifted the poem to the light, revealing the very watermark described on the unlocated copy. Was the world unaware that Middlebury held this literary treasure? Could these poetry detectives have solved the case of the missing manuscript?

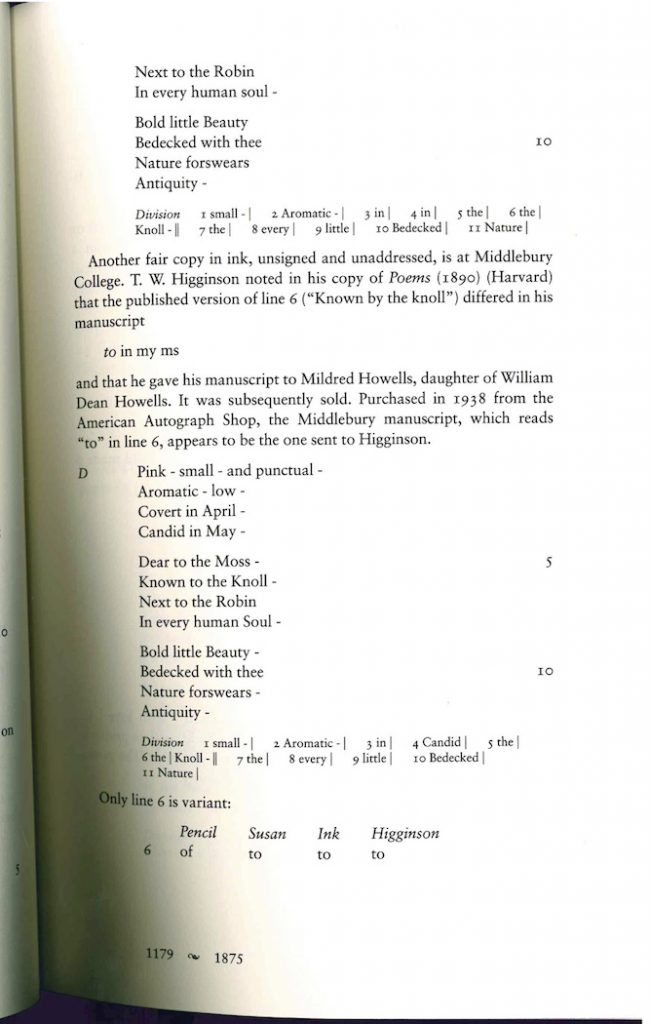

Upon further research, we found that the location of the poem had been discovered at some point after Johnson’s 1955 publication (a second edition in 1979 has the same information) and before another popular edition of Dickinson’s poems by Ralph Franklin in 1998. At some point between these two publications, the manuscript’s location was identified as Middlebury College’s Abernethy Collection. Franklin describes the custodial history of the manuscript, unknown to Johnson in 1955: This “fair copy in ink, unsigned and unaddressed, is at Middlebury College” (Franklin). He goes on to identify the poem as likely belonging to Dickinson’s mentor, T.W. Higginson, as the copy in his possession also contained the phrasing “known to the knoll.” In the first published edition, editors chose the variation “known by the knoll.” Franklin writes, “Higginson gave his manuscript to Mildred Howells, daughter of William Dean Howells, [and] it was subsequently sold. Purchased in 1938 from the American Autograph Shop, the Middlebury manuscript, which reads “to” in line 6, appears to be the one sent to Higginson” (Ibid).

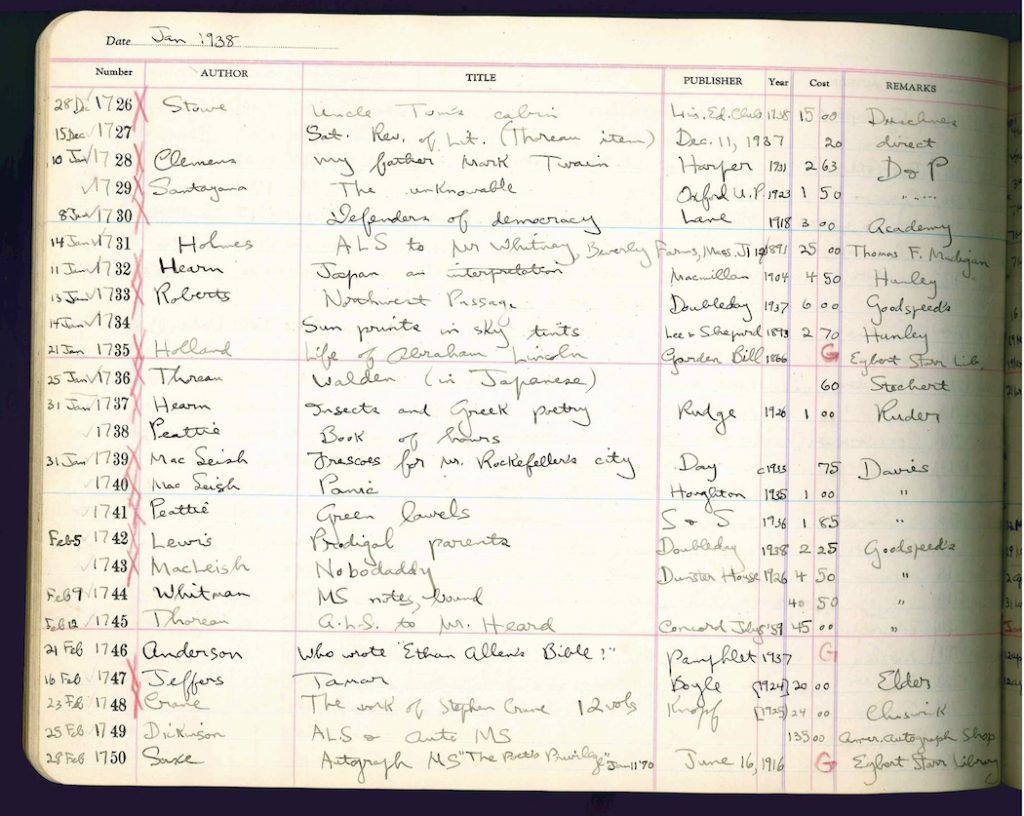

We corroborated this history by checking the library records kept by Middlebury curator Viola White, and indeed, she lists the purchase of Emily Dickinson manuscripts for $135 from the American Autograph Shop on February 25, 1938 (line 49).

Although the Poetry Detectives students’ discovery was not entirely new, it served as an exciting and important learning experience, which we hope it will lead to more interest in this manuscript and its inclusion in Harvard’s digital archive of Dickinson’s manuscripts. For more information about our Emily Dickinson manuscript and other little-known manuscripts in our collection, visit go/aspace.

Sources:

“About Emily Dickinson Archive.” Accessed September 22, 2017. http://www.edickinson.org/faq.

Dickinson, Emily, and R. W. Franklin. The Poems of Emily Dickinson. Variorum ed. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998.

Dickinson, Emily, and Thomas Herbert Johnson. Poems: Including Variant Readings Critically Compared with All Known Manuscripts. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1955.

Eberwein, J. D. “Corrective Vision: Franklin’s Dickinson Variorum.” Resources for American Literary Study, vol. 26 no. 2, 2000, pp. 260-267. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/rals.2000.0021

“I’m Nobody! Who Are You? The Life and Poetry of Emily Dickinson.” The Morgan Library & Museum, April 15, 2016. http://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/emily-dickinson.

“The Manuscripts | Emily Dickinson Museum.” Accessed September 22, 2017. https://www.emilydickinsonmuseum.org/emily_manuscripts.

“Manuscript View for Amherst – Amherst Manuscript # 329 – Pink – Small – and Punctual – asc:11465 – P. 1.” Accessed September 22, 2017. http://www.edickinson.org/editions/3/image_sets/95203.

“The Posthumous Discovery of Dickinson’s Poems | Emily Dickinson Museum.” Accessed September 22, 2017. https://www.emilydickinsonmuseum.org/posthumous_publication.

“Thomas Wentworth Higginson (1823-1911), Correspondent | Emily Dickinson Museum.” Accessed September 22, 2017. https://www.emilydickinsonmuseum.org/node/70.