This guest post is by Sam Cartwright, ’18, student employee of Special Collections & Archives.

The early history of photography is filled with laborious, finicky processes as idiosyncratic as the tinkerers who blended art and science to invent them. There’s the daguerreotype, the first and most otherworldly of the bunch which requires viewing its mirrored metal surface at an angle — and developing it with poisonous mercury fumes. There’s the calotype, a painterly reflection of reality imprinted directly onto paper not unlike the cyanotype, a dreamy blue-tinted print. And then there’s wet-plate collodion.

By making a thin layer of collodion (the syrupy result of dissolving guncotton in ether and alcohol) light sensitive then exposing and developing it before it dries, an image can be made onto metal or glass. Early metal plates used in the process were made out of tin, begetting the fitting “tintype” moniker that quickly became a misnomer once iron plates were adopted as a superior substrate.

The wet-plate collodion process was introduced to the world in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer. At the time, Middlebury had just celebrated its semicentennial but was troubled by dire finances, worrisome faculty turnover, and a burnt-out president. One hundred and sixty-five years later (a time with a notably brighter institutional outlook), I began an ongoing project to explore the technical intricacies and unique beauty of the tintype process while here at Middlebury.

Photography was a major part of my creative upbringing and sense of family history; my great-grandmother’s stunning panoramas of the American West adorned the walls of my childhood home and film photography has been one of my main creative outlets since middle school. At the tail end of my first summer away from Middlebury, I took a workshop on the tintype process at the Kimball Art Center in Park City, Utah — a fitting echo of my mother’s experience in that same darkroom learning how to make cyanotypes in her early twenties.

I was immediately hooked and began to plan a wet-plate developing setup here at Middlebury. Thankfully, there was already a student-run darkroom in the Forest Hall basement that was supportive of the endeavor and after a few months of gathering materials, I was able to start putting collodion to plate during my February Break.

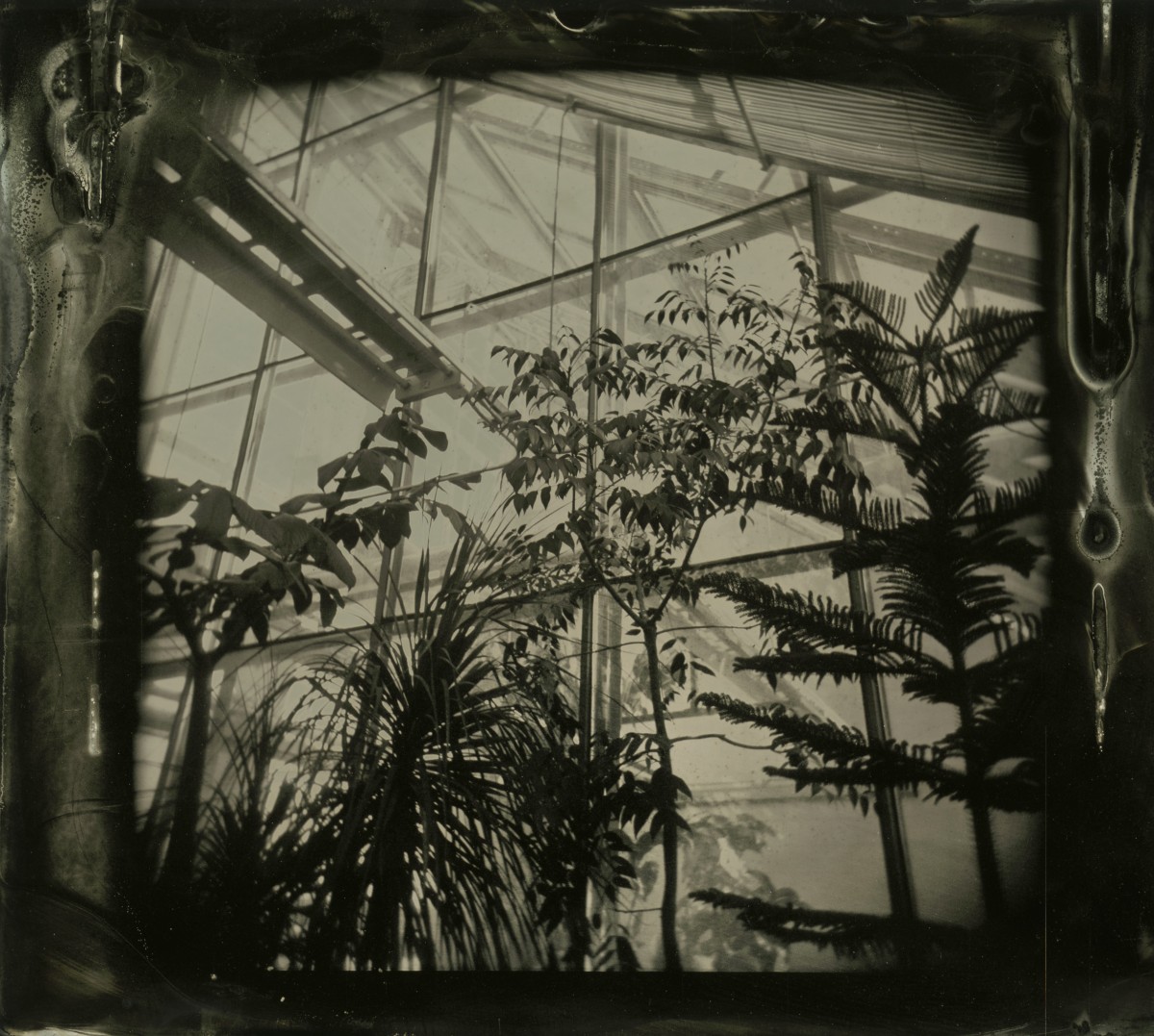

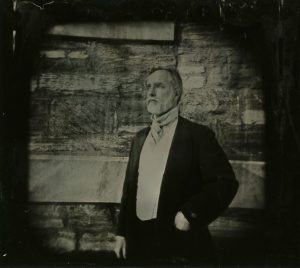

Over the course of that week and a few ensuing weekends, I shot a total of 73 plates with my Holga, a simple plastic-lensed camera. Each plate measures 3.5 by 2.5 inches and is made of aluminum trophy metal with a black coating, which is the more affordable modern version of Japan-lacquered iron plates used in the 1800s.

After carefully flowing a mixture of collodion and bromo-iodide salts onto the plates, they were sensitized in silver nitrate. I then had about 15 minutes before the collodion dried, giving me just enough time to fast-walk across the freezing-cold campus to make a 5-15 second exposure. After developing and drying, the final step in the process was to coat each plate with a lavender oil-infused sandarac varnish; warming the plates and varnish over our electric range made my Gifford suite smell like lavender for days — to either the delight or chagrin of my suitemates.

About half the plates depict scenes across campus, my favorite of which are those taken in the Bicentennial Hall greenhouse. The other half are portraits of friends who had just the right amount of curiosity and patience to bear with me as I got used to the process. In the end, my exploration of the tintype proved to be just what I’d hoped: a humbling technical and artistic challenge and a tangible connection to the history of photography. Once armed with a better camera and larger plates, I hope to continue the project.