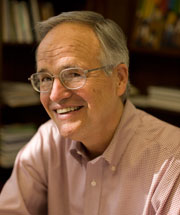

I’m very pleased to be announce that Gus Speth will join the School of the Environment as a Fellow this summer, both talking informally to the students about his life as an environmental leader and giving a formal lecture, which will be open to the public. Throughout his career, James Gustave “Gus” Speth has provided leadership and entrepreneurial initiatives to many task forces and committees whose roles have been to combat environmental degradation and promote sustainable development, including the President’s Task Force on Global Resources and Environment; the Western Hemisphere Dialogue on Environment and Development; and the National Commission on the Environment. Among his awards are the National Wildlife Federation’s Resources Defense Award, the Natural Resources Council of America’s Barbara Swain Award of Honor, a 1997 Special Recognition Award from the Society for International Development, Lifetime Achievement Awards from the Environmental Law Institute and the League of Conservation Voters, the Blue Planet Prize, and the Thomas Berry Great Work Award of the Environmental Consortium of Colleges and Universities.

I’m very pleased to be announce that Gus Speth will join the School of the Environment as a Fellow this summer, both talking informally to the students about his life as an environmental leader and giving a formal lecture, which will be open to the public. Throughout his career, James Gustave “Gus” Speth has provided leadership and entrepreneurial initiatives to many task forces and committees whose roles have been to combat environmental degradation and promote sustainable development, including the President’s Task Force on Global Resources and Environment; the Western Hemisphere Dialogue on Environment and Development; and the National Commission on the Environment. Among his awards are the National Wildlife Federation’s Resources Defense Award, the Natural Resources Council of America’s Barbara Swain Award of Honor, a 1997 Special Recognition Award from the Society for International Development, Lifetime Achievement Awards from the Environmental Law Institute and the League of Conservation Voters, the Blue Planet Prize, and the Thomas Berry Great Work Award of the Environmental Consortium of Colleges and Universities.

In short, there are few people who can speak more authoritatively or with more breadth of experience about what it will take for students to become effective agents of environmental change than Gus Speth.

He is the author, co-author or editor of seven books including the award-winning The Bridge at the Edge of the World: Capitalism, the Environment, and Crossing from Crisis to Sustainability and Red Sky at Morning: America and the Crisis of the Global Environment. His latest book is America the Possible: Manifesto for a New Economy, published by Yale Press in September 2012.

He is currently on the faculty of the Vermont Law School as Professor of Law. He serves also as Distinguished Senior Fellow at Demos, Senior Fellow at The Democracy Collaborative, and Associate Fellow at the Tellus Institute. In 2009 he completed his decade-long tenure as Dean, Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. From 1993 to 1999, Gus Speth was Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme and chair of the UN Development Group. Prior to his service at the UN, he was founder and president of the World Resources Institute; professor of law at Georgetown University; chairman of the U.S. Council on Environmental Quality (Carter Administration); and senior attorney and cofounder, Natural Resources Defense Council.

Stay tuned for more information about the title, timing, and location of his public lecture. If you are in the area, it will be well worth attending!