Curt and I, as the Co-Directors of the Middlebury School of the Environment, are hosting monthly webinars to discuss about the transitions and transformations of environmental challenges. The first was done on Ocboter 31, 2018, in which I opened with a short presentation about China’s environmental challenges and some efforts that have been made by the government, local and international NGOs, and other practitioners. Curt followed with a walkthrough of the Adobe Spark page he created (see the post below, and here: https://spark.adobe.com/page/lCJCm3sXRAFaL/) to share our experience last summer. Hope you enjoy watch/read them:

Author: Liou Xie

Author: Liou Xie

A tip-to-toe summary of MSoE in 2018

Utilizing Adobe Spark, an interactive multimedia tool, we summarized on our summer 2018 in China and would love to share with you about this colorful experience. Click the link below, and scroll down to read our story.

A quick peek of MSoE in action in summer 2018

[vimeo 298413846 w=640 h=360]

Middlebury School of the Environment from Middlebury College on Vimeo.

三道茶 (three-course tea): This is life.

After experiencing tie-dye, we went to a local Bai people’s house for lunch, who also served us their traditional three-course tea that represents different stages of life. In other words, “Bitterness, sweetness, and the aftertaste.”

The first course: bitterness. The tea server heats a small clay jar on charcoal, puts some tea leaves in and roasts them by turning the jar. Then she pours in boiled water and serves about half a cup of the tea to the guests. In the color of amber, the tea has a special burned smell and tastes bitter. It represents that you have to endure the bitterness of the first part of your life to achieve personal growth and a successful career that usually involves hard work and growing pains.

The second course: sweetness. After a similar process of heating the jar, roasting the tea leaves and serving with boiling water, the tea server adds brown sugar, diced Bai cheese, cinnamon, and sesame, etc. in the cup before pouring the tea. This aromatic sweetness is our reward for the hard work and achievements during the second stage of our life.

The third course: the aftertaste. The same procedure as the second course, but the ingredients in the cup is changed to honey, roast rice, numbing pepper, red pepper, and ginger. It’s served 60-70% full. Obviously, it offers all tastes for your tasting buds. It represents that during the last stage of your life, when you think back, all that life had for you come back with mixed long-lasting aftertaste and emotions.

Distilled from the wisdom of life that passed from generation to generation among the Bai people, three courses of tea cover all the stages of your life. It encourages you to be brave, to work harder, to embrace failure and disappointment, and to look forward to a brighter future. I feel that I could use some of this wisdom and encouragement from time to time in my life.

Apparently, there is a lot to think about when drinking this tea:

Sustainability Practicum Weekly Reflection 3

This is the last week we are spending in lovely Xizhou. Aren’t you feeling a little bit sad, having to leave behind all the connections you’ve made and not being able to see the amazing sunset on the mountain again after transitioning to Kunming?

For this week’s reflection, please think of your favorite place/person/phenomenon in Dali that you consider having some strong sustainability implications. Discuss why in specifics. And look into the future weeks in Kunming, what are your expectations for whether you will be able to find something similar, or comparable, in the big city?

Post your essay as a comment to this post by Thursday, July 5th, at 11:55 pm (Beijing time).

Above the clouds

Before yesterday, I would never have thought that I could have made it to a high elevation hike. Don’t get me wrong. I love hiking. The high elevation is what intimidates me. For months I’ve been saying no to hiking excursions unless I could carry oxygen tanks (plural) with me. Yak herders village deep in the mountains sounds cool. But oxygen sounds cooler.

Then yesterday came when I had to lead a group of students to hike the Jizu Mountain, of which I had no idea of the elevation. As a famous Buddhist sacred mountain, there are over 100 big or small temples dotted in it. There are also Taoist and local Benzhu temples. I thought it was just a short hike that even Eloise could handle and then a cable car ride to Jinding Temple at the top of the mountain. Easy peasy. So I didn’t even bring much snacks or water. After we got there after a two-hour drive, guess what, the cable car was closed for maintenance. Fine, we are on foot.

At first, it didn’t seem bad at all. 4720m (distance) seemed totally doable. We chatted and laughed while walking up, and said no to people who tried to convince us to get on a horse ride upward. Passed through some monkeys’ territory who seemed to have got used to tourists around. Even friendly.

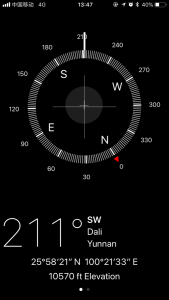

Then flights and flights of steps showed up, I started to have a hard time getting enough air in my chest. Quickly I fell behind. And curiously, I checked the elevation – just under 7,000 feet. Not too bad – I kept telling myself while taking a break every now and then. UNTIL some seemingly forbidding steps came into sight. “How high is this thing?” The more I went up, the more I doubted if I could make it. But the more I climbed, the more I felt I’d regret if I didn’t go all the way up. While torn between this overwhelming self-doubt and a tiny hope for a personal breakthrough, I went up slowly but steady. At a certain point, I had to take a break every 50 steps. Along the way, I noticed the changes in vegetation. Part of it was almost like a rainforest. Everything was wet and slippery. It was a little hard to hold my feet on the stone passage. I felt I was completely surrounded by water.

I had to take a long break and get some snacks at one of the food tents along the way. This man makes THE BEST potatoes ever! It was so good that one of my students ate FOUR of them! We sat down and had a conversation with him, and learned that he lives at the foot of the mountain, and makes a 14km round trip everyday high up here to support two monks by cooking two meals for them. To be able to support them, he brings up and sells water and food to tourists like us. THIS, is what I call dedication. While we were enjoying the potatoes, an allegedly famous Taoist stopped by and said hi to everyone. Seeing so many people under the tent, he sat down, took out his 箫 and played some super refreshing music for us.

After the break at the tent, we were told that it would take another 50 minutes to get to Jinding temple. I was very close to giving up. But I saw everyone trying their best to keep going. Strangers say 加油!to me while passing by. Everyone was exhausted but with big smiles. Somehow, that kept me going and going. For maybe the last 10 minutes of the hike, I felt much better with my breaths and the hike actually started to become easier. I wonder if that was because my lungs got a little used to the oxygen level. I have to say that I looked miserable when I finally made it to the top. The trip took me 4 hours.

There at the top, the elevation was almost 11,000 feet. I was shocked when I saw the number. 4720m compounded by 4,000 feet elevation rise is actually pretty significant. I would never have done it if I knew it from the beginning because my mind would have given up already. In a certain sense, not knowing was actually helpful.

It was an amazing view at the top, standing above the clouds. Everything looked small, so was the world. Every bit of thoughts that bothered me didn’t seem to matter at that moment. The all white pagoda was quite different from all other pagodas I’ve seen before elsewhere. It felt quiet and tranquil. When I stood on the flat ground in the temple and looked around, there was not much but the clouds. At that moment I realized why the temples are always built on the top of the highest mountain and the monks seek seclusion for self-cultivation/meditation. When all you see is nothingness, the only way to look is inward.

Although today my legs felt like two chopsticks that don’t bend, this was the best experience I’ve ever had. Being above the clouds is an experience that won’t be forgotten.

Lastly, look at this kid who is totally obsessed with the lichens – what a reward after a long day of tough hike. Bravo, kids.

Sustainability Practicum Weekly Reflection 2

As a group, we have learned about the history of China since the mid-1800s. We have also been exploring the town and nearby areas in our classes and during our free time. Please reflect on your experiences so far, find an incident, be it an object or a place or a phenomenon or anything, that you think connects with one part of the Chinese history, and discuss it.

Be specific, be inspiring, be insightful.

Post your essay as a comment to this post by Thursday, June 28th, at 11:55 pm (Beijing time).

Sustainability Practicum Weekly Reflection 1

The first week of Sustainability Practicum focuses on Mike Kiernan’s workshops on Leadership skills, Storytelling and Persuasive speaking, your observation and activities in town and with local people.

For your first essay, we would like you to reflect on what you have learned from the workshops, and summarize your personal experiences so far.

Post your essay as a comment to this post by Thursday, June 21st, at 11:55 pm (Beijing time).

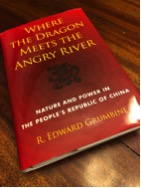

A Book Review

A book review by Dr. Curt Gervich, of R. Edward Grumbine’s Where the Dragon Meets the Angry River: nature and power in the People’s Republic of China (Island Press, 2010).

“When an untamed river encounters a dragon, what happens next?”

Caption: Dragons and Rivers in Yunnan Province, China.

That’s my favorite quote from R. Edward Grumbine’s Where the Dragon Meets the Angry River: nature and power in the People’s Republic of China (Island Press, 2010). The Angry River digs deep into the central questions that haunt conservation efforts in China and that form the central themes of the Middlebury School of the Environment’s curriculum in China. With years of experience in Yunnan, Grumbine explores topics such as how Yunnan is balancing the need for conservation with energy development; how rural communities in Yunnan are keeping pace with economic development in China while retaining rural character and culture; and how conservation efforts and policies can be effective in China against the backdrop of a wickedly complex bureaucratic governance structure that prioritizes economic development and centralized decision making above all else.

“China has never had a Henry David Thoreau, John Muir or Terry Tempest Williams. The country was shut off by the party from most international influences during the formative decades of the U.S. wilderness movement. Nature protection in China is rooted in a different soil.”

(Ed Grumbine, Where the Dragon Meets the Angry River: nature and power in the People’s Republic of China. Page 34.)

Not only does The Angry Dragon offer an in-depth perspective on environmental conservation in Yunnan Province, China– it also features many places students aboard the Middlebury School of the Environment may have the opportunity to experience in summer 2018. For example, Grumbine examines the urban development strategies of several communities in Yunnan, including Dali, Liejang and Kunming.

The Linden Centre, where MSoE is based when in Dali, is a 20 minute taxi ride from Dali’s historic old town. Here are some pictures of Dali’s historic centre from our recent planning trip:

Caption: Day and night in Dali.

Liejang is about 120 minutes north west of Dali and also has a preserved old town, though it’s quite different from Dali. Kunming is about six hour south, and is home to six million people. It will be fun for students to experience the social-ecological systems of all three places.

In Angry River Grumbine details the role of The Nature Conservancy in biodiversity conservation in Yunnan. Middlebury School of the Environment is in the process of developing a multi-day conservation boot camp with The Nature Conservancy in Yunnan. This experience will take place at TNC’s migratory waterfowl and wetland conservation project at West Caohai. Our collaboration will focus on TNC’s conservation planning process from start to finish. It will include problem identification and scoping, data collection and analysis, education and policy development. Here’s the link to TNC’s China website.

And a few pictures of our trip to the West Caihai wetland site:

Caption: Middlebury and TNC staffers developing conservation boot camp at West Caohai.

Having returned from Yunnan in October and seen the sites and issues Grumbine details first hand, I have a few observations that I am excited to continue exploring with MSoE students in 2018. First, western China may be among the most under-appreciated and least well known biodiversity hotspots in the world. The eastern Himalayas contain an astounding array of ecosystems, rare and endemic species, and other gems. As Grumbine notes, the rivers that begin in this region drain an enormous percentage of Asia’s landmass, and are used by billions of people. That’s billions with a B. The geographic, social and economic scales of this place are of such a magnitude that they are difficult to comprehend. Second, Yunnan both reflects and rejects many of our assumptions about life in China, and the ways that social life is intertwined and dependent upon the environment. Finally, environmental professions and efforts in China are as varied and lively as anywhere. For example, environmental work in China is not only about biodiversity and energy– the functional areas we often hear about in the news. Environmental art, and sustainable food systems work are abundant and innovative. Here are some pics from a farm-to-table project we visited outside Dali:

Caption: Food systems innovations are as hot in Yunnan as in Middlebury Vermont. Farm-to-table experiments!

Environmental work is a grand experiment anywhere. It doesn’t matter if you’re in Vermont, on a college campus, or in China’s hinterlands. Yunnan province offers a new take on this experiment and is contributing to our growing body of knowledge in unique ways. Grumbine’s book has a lot to teach about conservation with Chinese characteristics.

R. Edward Grumbine is a professor of conservation biology at Prescott College. He also serves on the Middlebury School of the Environment advisory board.

No. This “shared space” won’t work. And well designed road signs don’t suck

1. There are many other ways to slow down cars than the stress from the presence of people and non-existence of signs/lights.

2. The decreased fatality data could be more contributed by fewer people/cars going through that shared space than the effectiveness of the design.

3. Believe me when I say I grew up in this kind of “shared space”. We called it “chaos” and I saw enough accidents. This is still true in many developing countries and they are striving to move towards less chaos. Why is Europe going backward?

4. I don’t have to repeat how dangerous it is for disabled or older/younger people.

5. Rather, widen the sidewalks, narrow the lanes, put up a reasonable amount of big signs and lights, the cars WILL slow down. And people will be safer.