Sound in video games is a subject that has always fascinated me, even from the early stages of my gaming experience. Soundtracks and music in particular have always been a crucial factor in my opinions of games, especially at an emotional level. Like visual aesthetics and landscape, I think there is something in music that really moves me in ways that gameplay, story, or competition never have. When I think back on what I would describe as the most beautiful video game scenes I have ever experienced, in almost all cases there is music involved.

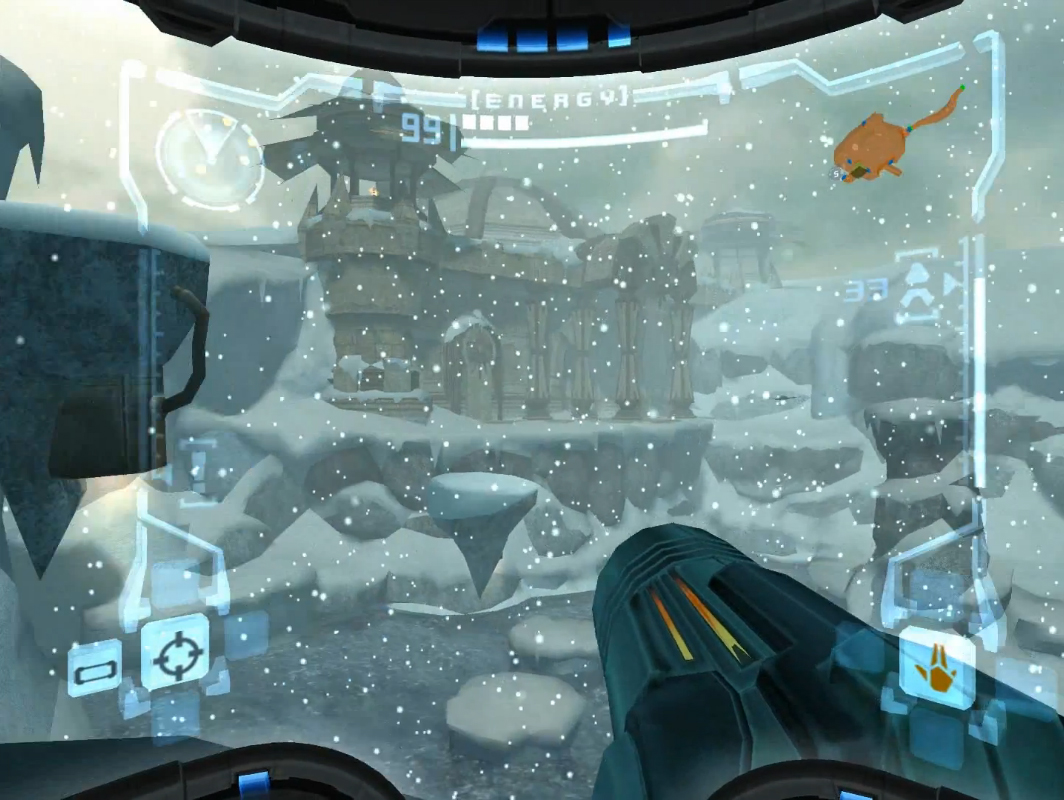

The Phendrana Drifts landscape from Metroid Prime always resonates with me, due in large part to the music and atmospheric ambience.

The Phendrana Drifts landscape from Metroid Prime always resonates with me, due in large part to the music and atmospheric ambience.

I have found that in most games, the potential of music depends greatly on the type of gameplay experience that it accompanies. For example, our playing this week of League of Legends has demonstrated to me that if the play style is focused entirely on in-game tactics and combat, the music almost inevitably takes on a background, ambient role rather than a central one. In other words, the gameplay itself is so engaging and distracting that little attention remains to appreciate things like music and ambient sound. Besides, the sound of combat far outweighs anything else.

At the other end of the spectrum, a game like Rock Band is entirely devoted to sound and music. The gameplay is the sound, so music acts not as a complement to the game, but as its foundation. For me, though, the best sound experiences in gaming are passive, in the sense that there is ambient noise and music that you can totally immerse yourself in, without having the feeling that you have to work to produce the sound. As is the case in Rock Band, the constant reminder that missing any notes ruins the song acts as a stressor that in many ways detracts from the sound experience.

One game that stands out in my mind as one in which sound and music are crucial is The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask. This is probably the game I have have played that has the most innovative soundscape, both musical and ambient. The theme of this game is the imminent running-out of time, with the omnipresent falling moon looming over the entire game, literally. As the three days progress, the music gets faster and faster, moving over time from a leisurely atmosphere to one of intense stress and chaos as the moon nears its apocalyptic collision with the planet’s surface. With the ever-increasing number of earth-shaking rumbles and the din of falling debris, sound adds a suspenseful dimension to the game that makes it remarkably realistic. Even the individual worlds within the game have their own soundscapes to offer; from the distorted underwater sounds of the ocean, to the dolorous and dissonant canyon, to the dank, drippy swamp ambience, to the cold, lonely mountains, this game has a uniquely characteristic sound environment for every region within the game. All of this, on top of the somber music in-game that casts a depressing (yet remarkably beautiful) pall over the entire experience.

Technically a musical tribute, but I think it captures the essence of the game well.

Technically a musical tribute, but I think it captures the essence of the game well.

Additionally, the game Slender is an exemplar of how important sound can be in a game. With the spooky background music and the crescendo of grinding ambient noise as the game progresses (broken sporadically by the slamming noise associated with encountering your terrifying foe), this game’s effect on the player is built almost entirely around sound. I can evidence this notion by saying that when I tried playing the game without the sound on – because I couldn’t handle the stress of it all – it seemed to lose almost all of the suspenseful intrigue that it previously had. Even though it was less stressful without sound, the gameplay experience was highly diminished nonetheless.

A few more examples of music that I see as definitive in games:

The hauntingly memorable “dancers on a string” sequence from Bioshock.

The hauntingly memorable “dancers on a string” sequence from Bioshock.

This recurring melody from the Legend of Zelda series is a great example of the combination of music and ambient sound effects (reminiscent of a forest, right?).

This recurring melody from the Legend of Zelda series is a great example of the combination of music and ambient sound effects (reminiscent of a forest, right?).

I know this one in particular evokes very strong emotions in a lot of people who grew up with Kingdom Hearts.

I know this one in particular evokes very strong emotions in a lot of people who grew up with Kingdom Hearts.

game franchises as Pajama Sam and Freddie Fish, I eventually graduated up to “big kid games” like The Sims and Rollercoaster Tycoon. I received my first gaming console, a GameCube, when I was 11 years old. My first game was Luigi’s Mansion. From the beginning I could tell that video games would continue to be a source of endless inspiration and amusement for years to come, because I found the experience of immersing myself in another world to be irresistible.

game franchises as Pajama Sam and Freddie Fish, I eventually graduated up to “big kid games” like The Sims and Rollercoaster Tycoon. I received my first gaming console, a GameCube, when I was 11 years old. My first game was Luigi’s Mansion. From the beginning I could tell that video games would continue to be a source of endless inspiration and amusement for years to come, because I found the experience of immersing myself in another world to be irresistible. (but are not limited to) Super Smash Bros., Okami, Pikmin, Metroid Prime, and some Mario platformers like Super Mario Sunshine and Super Mario Galaxy.

(but are not limited to) Super Smash Bros., Okami, Pikmin, Metroid Prime, and some Mario platformers like Super Mario Sunshine and Super Mario Galaxy. fashioned Super Smash Bros. ass-whooping as much as anybody. In spite of (or maybe because of…) my aforementioned individualistic gaming tendencies, I am actually insanely competitive. I often have trouble dealing with losing even the most trivial of games, to the point where they can sometimes become another stress in my life rather than an escape (I think many of my closest friends can attest to that). Hence, in some situations I find it best to avoid games like Mario Party for the sake of my personal relationships.

fashioned Super Smash Bros. ass-whooping as much as anybody. In spite of (or maybe because of…) my aforementioned individualistic gaming tendencies, I am actually insanely competitive. I often have trouble dealing with losing even the most trivial of games, to the point where they can sometimes become another stress in my life rather than an escape (I think many of my closest friends can attest to that). Hence, in some situations I find it best to avoid games like Mario Party for the sake of my personal relationships. iPhone games in general) will never achieve a comparable level for me. To demonstrate my point, I would contrast Bioshock with another shooter such as Call of Duty. In the latter, it seems to me that the sole purpose of the game is simply to destroy the opposition at all costs, a style of gaming that has always struck me as somewhat mundane. In Bioshock, though, I find that there is so much more substance – the art-deco, underwater-city setting is one of the most incredible scenes I could ever imagine, the story is addictingly immersive, and attention to details such as music and voice acting make its imaginary world even more awe-inspiring.

iPhone games in general) will never achieve a comparable level for me. To demonstrate my point, I would contrast Bioshock with another shooter such as Call of Duty. In the latter, it seems to me that the sole purpose of the game is simply to destroy the opposition at all costs, a style of gaming that has always struck me as somewhat mundane. In Bioshock, though, I find that there is so much more substance – the art-deco, underwater-city setting is one of the most incredible scenes I could ever imagine, the story is addictingly immersive, and attention to details such as music and voice acting make its imaginary world even more awe-inspiring.