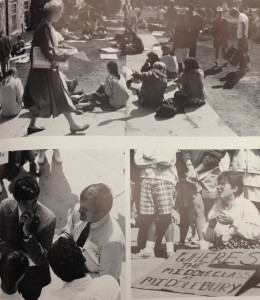

Students form STARTUP (Students Against the Rise in Tuition and Unjust Policies) and half the student body boycott classes and stage a sit-in on Old Chapel steps.

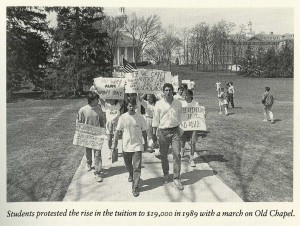

Students protested the tuition rise in 1989, where half the student body boycotted classes on May 4th AND there was a sit-in on Old Chapel steps! “What began as a murmur of dissent crescendoed into a resounding call for addressing the definite adjustments in Middlebury attitudes. Campus attitudes have transformed from a pervasive political apathy to a new awareness and a determination to challenge Middlebury norms. This new awareness demands more student involvement in campus affairs and a reclaiming of the student voice.” From 1988-1989 the annual comprehensive tuition fee increased from $17,000 to $19,000. Source: Kaleidoscope 1989; Stameshkin p.214

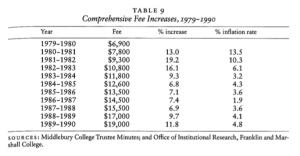

“By the 1960s the great majority of Middlebury students – in sharp contrast to the profile in 1915 – could be classified as upper-middle or upper-class…Only the desire to improve quality and keep pace with rival schools finally shaped the decision to attract wealthier students and more income” (Stameshkin, 187). When President Robison took office in 1975, a mere 18% of the student body was on financial aid, and there was an increasingly prevalent sentiment that Middlebury College was an “upper-class preppy” college and that less affluent students ought not bother to apply. Finally, in 1980, Robison proposed a need-blind policy to the board of trustees, and in the spring of 1982, after aid-blind admissions had been set, the number of admitted students on financial aid increased to 30%. The implementation of this policy – in addition to renovations, new programs, and additional faculty and staff hires – was, argued Robison, the driving force behind significant comprehensive fee increases from the years of 1979-1990 (Stameshkin, 212-213). During the three years prior to 1990, the Robison administration had tried raising fees to match the ever-increasing costs of long-term expenditures – such as added laboratory/office space and maintenance fees – which had seen an average annual increase of 19.3% (Stameshkin, 178). In the years after 1983, when the national inflation rate averaged around 4.65% for each year, the annual rise in the Middlebury comprehensive fee was approximately 7.4% (Stameshkin, 212-213). Things changed in 1989 after comprehensive fees increased from $17,000 to $19,000, an increase in 11.8% in one year. In a Letter to the Editor in the March 24, 1989, issue of The Middlebury Campus, entitled “Is tuition the only evidence of consistent growth?” one student named Michael B. Campbell ’90 wrote, “I have silently sat back and watched the comprehensive fee at Middlebury increase from $14,500 during my freshman year to $19,000 during my last year at ‘Clubb Midd.’ I am thankful that this is the last tuition increase I will have shoved down my throat.”

By mid-April of that year, a group called STARTUP (Students Against the Rise in Tuition and Unjust Policies), consisting of sixteen juniors and seniors, had formed on campus. STARTUP leaders David Milner ‘90 and Rob Gray ’90 called for a boycott of classes on May 4, 1989. Half the student body boycotted classes on this day and several staged a march and sit-in on Old Chapel, bearing signs that read words such as “WE CAN”T AFFORD OUR BIG FAT SCHOLARSHIPS”, “11.7% PROMOTES HOMOGENEITY NOT DIVERSITY,” “INFORM YOURSELF,” “11.7% PROMOTES ECONOMIC DISCRIMINATION,” and “AFFORDABILITY BEFORE PRESTIGE.” Other students hung towels over their dorm windows in solidarity with the protest movement, as if to say they were not “throwing in the towel” just yet. Others still signed a petition with 700 signatures protesting the tuition hike and promised not to donate to the college after graduation. Faculty members in solidarity with the movement wrote letters of support to the group heads. The Middlebury Campus front-page story from September 15, 1989, entitled “Student strike leads to limited discussion,” discusses the event and a series of meetings that occurred between Milner, Gray, Robison, and other administrators in the weeks following the boycott.

In the initial meeting on May 8th, Milner and Gray voiced STARTUP’s four demands to Robison: a reduction in the comprehensive fee increase to 7%, the implementation of a student as a voting member of the Board of Trustees and its budget committee, an itemized account of tuition dollar spending, and a tuition guarantee specifying tuition hikes over a student’s time at Middlebury. On May 27th, Milner and Gray presented these demands to the Undergraduate Life Committee of the Board of Trustees. Nothing concrete was set, and the Board admitted it was too late in the year to reduce the comprehensive fee increase as it was, but they were willing to discuss the latter four of STARTUP’s demands. Of the meeting with Robison, Milner says that it was very much “no, no, no, and no, and that took three hours to accomplish.” They were, however, able to establish a committee – comprised of Milner, Gray, Director of Residential Life, and College Treasurer – to look into cost cutting. Overall, Milner and Gray expressed disappointment with the two meetings. Still, other students seemed satisfied with STARTUP’s ability to mobilize students during the strike. Kristin Ness ’89 said, “students should keep up the effort to keep tuition increases reasonable, so the movement does not fade into one of those ‘trendy’ issues.” The Campus article concludes with the promise that STARTUP would remain active during the 1989-1990 school year, with Milner and Gray especially interested in the Justice Department investigation into possible anti-trust violations involved in setting tuition rates at Middlebury and several other “prestigious” colleges and universities.