Following the departure of Tony Lupien, then Middlebury’s most successful coach in program history, the team endured a decade of futility, failing to win more than five games in any season under its enthusiastic, but over-matched coach, Stub Mackey. After eight years and a total of 21 wins, Mackey moved on and was succeeded by Gerry Alaimo, a young, energetic coach who had dominated the Ivy Leagues as a player. Due in part to a revamped schedule and a developing recruiting process, Alaimo’s teams fared little better than Mackey’s over his first four years, in which he totaled just 11 wins. Like Mackey, Alaimo coached some talented players who chose to attend Middlebury for it’s location, academics, or the promise of competing at the varsity level multiple sports. But like Mackey, while Alaimo’s teams had a handful of talented players, they lacked the depth necessary to effectively come off the bench and spell starters or play extended minutes in case of injury. Middlebury basketball hit its nadir during 1966-67 and 1967-68 seasons with consecutive 1-22 finishes. During that stretch the Panthers not only set the NCAA record for consecutive losses, they obliterated it, more than doubling the previous mark of 18 with 44 straight defeats.

And yet, in spite of the mounting losses — and perhaps in part because of them (one could argue that losing to top teams made Middlebury more competitive) — the nucleus of a successful run to close out the decade was being formed. While Alaimo’s tenure was ultimately short-lived, his intensity, exacting style and tireless recruiting formed the foundation of a decade of success.

Part I: “I played basketball at Horace Mann and we were fortunate enough to have an undefeated basketball team my senior year. We’re going to go from 17-0 to 0-17.”

Wally Lucas: As a kid I would spend the summers in Burchard, Vermont with a family, and I became very close with that family and very close with Vermont. Then I won a scholarship to Horace Mann school, a preparatory, private school in New York City. I played basketball [there] and we were fortunate enough to have an undefeated basketball team my senior year. We’re going to go from 17-0 to 0-17.

Craig Stewart: The wife of my football coach in high school was a Middlebury graduate and she and her husband said, “If you go to Middlebury you’ll be able to play three sports.” So I went early my freshman year, fully with the intent of playing football, basketball and baseball. I reported to football camp in August and met a lot of guys there who were also going to play basketball. Stub Mackey was the line coach [of the team] and I was a running back and quarterback, so I got to meet him. And Stub said, “As soon as the season is over we’ll change that uniform.” And I said, “Yes sir.”

Stub was a football coach who was asked to coach basketball because there wasn’t great interest and there certainly wasn’t great success in the late ‘50s [and] early ‘60s.

Joe McLaughlin: Stub was primarily a football and track coach, and I don’t think anyone was under the impression that his first sport at Middlebury was basketball. He put in a fairly simple offense that probably was well-suited to our limited talent. I think players liked him — he was very philosophical about the talent that he had. Middlebury basketball at that time was kind of a stepchild. Hockey and skiing were the dominant winter sports. We had maybe 20 people at games down at the field house. So it was not a sport that held much interest among the rest of the campus.

Stewart: [Stub] used to joke that the only time we got a crowd was in between periods when the hockey fans would come over to get warm in the basketball arena.

Karl Lindholm: We’d have games where there were 200 or 300 fans … for a minute or two. They would come into the gym to get warm at the period breaks in hockey. We had one game, it was right near the end — the score was tied with a minute to go, or something — and there were a lot of fans standing at the doorway to the gym watching the game, and somebody yelled, “The hockey game started up!” and they all left. And we all thought “You could stay a minute and see what happened!”

McLaughlin: Stub was kind, he was long-suffering and he didn’t know a great deal about the game. But having said that, even if he did he didn’t have the players to really execute at the kind of level [to win]. But he was a great guy, he was fun to be with and he was a character; he was just one of those memorable human beings.

I think he made this comment on a bus, coming home from UVM or St. Michaels — two schools that I never beat [when I was at Middlebury]. He said something like, “We may not be big, but we sure are slow.” He had a very wry sense of humor.

Forster: We lost our share of games as a Middlebury basketball player. It humbled me; it made me realize, as good as I thought I was, that losing was part of my life experience.

McLaughlin: I remember Dick Maine who [eventually] was the captain. Dick was the year ahead of me and he was interviewing for jobs and he encountered one interview where the interviewer asked him about the basketball team and Dick said, “We won 17 moral victories.” I think that was the year we didn’t win any games at all.

Lucas: We were about to set the NCAA record for most consecutive losses and we screwed that up. Everyone came out to watch the game and we won — we beat Norwich at home.

Stewart: All of the good players got frustrated with Stub and the program and found their greatest joy and greatest success playing in the intramural program. I got to play almost every minute of every game because there wasn’t anyone else. We were lucky to have 10-12 guys on the team.

Lucas: I was also captain of the track team of which Stub Mackey was also the coach. I had a very nasty hamstring tear [my senior year] the week before my comprehensive [exams]. The comps were very important — if you didn’t pass that, you didn’t graduate. And there was no way I could run in the track meet before my comps. And he was disappointed, but I know that disappointment went farther — there was definitely an attitude throughout the field house. [The trainers] would tell me about how certain football players would play hurt … they were really getting into a thing, as if athletics were ruling the campus life. And I said, “Wait a minute guys, I didn’t come to Middlebury to risk my health and flunk out of here. These were my priorities, my comprehensives, so I didn’t go … I couldn’t run anyway.” So it became such a big deal that I quit [the track team].

[And then one day] I was jogging around the track and I bumped into Stub and I walked over to him and said, “Hey Stub, I just want to let you know this isn’t personal between you and me.” And we had a chat and he gave me a philosophical view that if I were to go through life with the attitude that I had, I would end up being a quitter in life. And that was the last conversation I had with Stub and it disappointed me because I was the one that overlooked whatever shortcomings he may have had as a coach and it seemed like he was closing ranks with the athletics department. So I said, “OK I’m still not going to take this personally, Stub, I’ll keep in mind the things that you’ve told me.” I’ve tried not to be a quitter in life, and I don’t think I have been. I still feel close to Stub, [I feel] no animosity towards him.

Part II: “Ted gets on the bus and all of a sudden this woman comes running out of his motel room yelling, ‘Ted! Ted! Where are you going?’”

Stewart: I’ll always remember Ted Mooney. Ted was a classic Vermonter. He was a pretty good basketball player, but Ted was a storyteller. [He] basically got all of us into trouble and tried to keep all of us out of trouble at the same time. Ted seemed to have a girlfriend at every school we traveled to, whether it was Plattsburgh or Williamstown or Middletown or Hartford or Burlington.

Forster: My freshman year — the fall of 1960 — we played in a tournament in St. Lawrence in up-state New York and we stayed in a motel for the two or three nights that we were playing. And Ted met some woman while we were playing in this tournament and she was staying with him at this motel while we were playing. And the day came when the tournament was over and we get on the bus to drive back to Middlebury, and Ted gets on the bus and all of a sudden this woman comes running out of his motel room yelling, “Ted! Ted! Where are you going?” [Laughs]

Stewart: We all gravitated towards Ted because he kept things in perspective and he helped us keep things in perspective. A lot of us had come from successful [basketball] programs in high school and one could have gotten easily discouraged and Ted kept us up and kept us always laughing. [I] still have dreams about [those guys] … I still have dreams about Middlebury basketball, oh my god.

McLaughlin: One of my best friends at college, Dick Ide was an extremely good soccer player and tennis player and a very good basketball player although he was only about 5’7’’ or 5’8’’. We created a memorial to him in the English department at the University of Southern California that memorializes his years at Middlebury. One of the stories that’s told had to do with a game at Williams where, in the second half, Dick got the tip [from the jump ball] and drove the length of the court, through two Williams defenders, and put the ball in the wrong basket. Of course the Williams crowd went wild with laughter, but Dick actually played a very good game, and scored a fair number of points in the second half after he realized what he’d done wrong. And after the game, the President of Williams College, who was at the game, came out on the court and shook his hand and said, “You showed a lot of poise.”

Forster: Being in a program where we were not terribly successful probably made me a better person. It made me understand that you have to find ways to take something out of the situation. And my senior year, while we didn’t win a lot of games, I remember with pride playing with Peter Karlsson and Billy Dyson and Dick Ide. It was almost like being a prizefighter: the other guy knew he was in a fight. When my friends who played at Notre Dame or Iowa or other big-time schools say, “You went to Middlebury?” I don’t flinch at all because I know I did good.

Lucas: Without sounding too trite, there are things called reality checks. Clint Eastwood in a movie once said, “A man’s gotta know his limitations.” [Laughs]. The reality check was coming from my high school environment — the glory days — where you had seven good players and you could think about winning as the only goal in each of those games. But up at Middlebury, there was something more to it. I’m sure if Craig and I got together over drinks we would talk what it was like representing the school, something bigger than we were, and being loyal to it, knowing that we probably wouldn’t win, but that we would play our best game. That’s not easy to put into words. I’m proud of it personally.

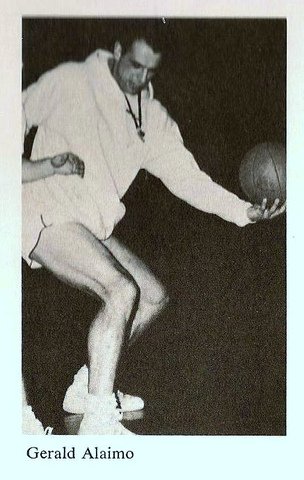

There was never a dull moment when Gerry Alaimo was your coach. Even during drills (as shown here) Alaimo managed to turn the routine into the eventful.

Part III: “I had the ball and Gerry said, ‘Roll that ball on the floor, I’ll show you how it’s done.’ And he dived on the loose ball and broke his wrist.”

McLaughlin: We all got a preview of what Gerry Alaimo was like during the first football game. There was a bad call out on the field and Gerry was standing down on the sidelines — and he’d been at Middlebury for a few weeks at this point — and he disagreed with the call, so he ran out on the field and started yelling at the ref. I don’t know what Duke Nelson thought about that, but it was pretty clear that he was driven.

Lindholm: Gerry was a breath of fresh air. I think he was about 28 years old, big guy — about 6’4’’ or 6’5’’, very animated. He just had such an overwhelming personality and was such a contrast to the guy who he succeeded, Stub Mackey who was a very likable guy, but his teams had been really unsuccessful.

McLaughlin: For him, basketball was his first love — basketball was his only love. As far as I know, Gerry never got married. Basketball was his life.

Rick “Clubbo” Minton: He was the all-time leading scorer at Brown. He was legendary in the Ivy League for how tough he was, and he was a tough guy. Not only did you have to go to class, you had to do well. He said you to go be in bed by 10 at night. There was no drinking during the season … people really didn’t even party on Saturdays.

Lindholm: Gerry always played up his blue-collar roots — he was an Italian kid from Torrington, Connecticut. Whenever you went and said, “I have to miss practice, Gerry, I have a test tomorrow,” he would say, “What you can’t give me an hour, you can’t give me two hours? I went to Brown and all I did was play bridge and I got through Brown.” He just wouldn’t hear it.

McLaughlin: There was a new energy level [when Gerry became coach]. Gerry was very high energy, very intense. He knew he was facing a challenge. He worked us real hard — his practices were brutal.

Lindholm: He knew we weren’t very good, so he said that we would be the best-conditioned team in the league, and I think we probably were.

Minton: Unless you had a lab that you had to take, you were supposed to be on the floor at 2:45. When practice started the doors got locked and if you weren’t in there or still in the trainer’s room, there was no practice. We just got on the line and ran suicides until the person showed up. And then when that person showed up they ran suicides for the rest of practice.

He had this drill, at the end of practice every day everybody would be on the free throw line with one-and-one [free throws] and if you bricked one you started running. There was one night when we must have run, I don’t know, 35 suicides. Jimmy Keyes was lying on the floor with his legs twisted with cramps. Guys were outside booting in the snow. And it was one of those practices — those brutal preseason practices or the holidays — when Kufta gave him the name The Fruit Vendor. We’re all on the line and huffing and puffing, going “make the fucking foul shots.” And Kufta just starts laughing like a hyena and says, “Doesn’t Gerry sound like a goddamn Italian fruit vendor?” And that was it, our loads were all lighter, we ran, we just kept running and that was it.

Lindholm: One day our tongues were hanging out after we had practiced for a long time and Gerry thought that our effort had begun to flag and somebody had been slow to dive on a lose ball. I had the ball and Gerry said, “Roll that ball on the floor, I’ll show you how it’s done.” And he dived on the loose ball and broke his wrist. Practice was over. You can look at one of the [old] pictures, you’ll see him with a big cast on his wrist.

But he really liked his players, and when he would come back later on [after he left], he would talk very fondly about everybody.

Keyes: When I was a freshman I lived in Stewart Hall and Gerry had an apartment in Stewart and he would, with some frequency, come cruising down the halls and see what was what. And if you weren’t studying he would get after you. When he was trying to teach me the hook shot he would say, “Let’s go down to the court.” And it might be eight o’clock on a Saturday night and we would go down and put the lights on and play one-on-one for an hour or two. And we did that a lot. He took a lot of personal interest in me, which I really appreciated.

McLaughlin: Gerry put in a new offensive system: something called the Yale Shuffle, which was popular in the Ivy League at that time and more complicated than what Stub ran, which was a simple rotation offesne. Gerry also spent a lot of time on individual defense. He was a very good coach in that respect; I learned a lot from him.

Lindholm: [Gerry] was all alone as the varsity coach. I remember I wasn’t playing much my senior year and our record was poor. So I went to Gerry and told him that I could beat the guy playing in front of me in one-on-one, nine times out of 10. And he said, “I believe you, Karl, but he’s a sophomore and you’re a senior, and we’re 0-11.” So I was kind of the de facto assistant coach. He knew I didn’t like not playing, so he’d say, “Come sit next to me. You’re in charge of finding out how many timeouts I have left.” He used to stand at the end of the bench when there was a problem and say, “My staff! Where’s my staff? That’s something my staff should have for me,” when he needed to know something about a game.

Part IV: “We had UVM beat; we were ahead by five points with a minute to go. And the way I like to tell the story, I lost the game all by myself.”

Lindholm: We had a lot of tough losses. I used to ask myself: was it a weakness on our part that we tried so hard to win and we couldn’t. Were we just pitiful? Should we have just taken it easier? The guys in ’65, Paul Witterman and Joe McLaughlin, joked a lot about the season and all the ways they didn’t train. We couldn’t get away with that with Gerry; we trained pretty hard — we tried hard — we just lost all the time.

The game I actually remember the best, it was my senior year — the one-victory year — and the second or third to last game was against the University of Vermont in our gym. And we had them beat; we were ahead by five points with a minute to go. And the way I like to tell the story, I lost the game all by myself. My man scored a basket to make it three points. I took the ball out and I threw a bad pass inbounding the ball … threw it to a UVM guy who drove to the basket. I fouled him, he made the basket and the foul shot, and our five-point lead was cut out in about four seconds, all by me. But we lost to them by two points. And a win against UVM in that miserable year would have really helped salve the wounds.

Keyes: The year before I came to Middlebury the varsity team was 1-22. The next year they were 1-22 also. In the first year they won the first game, and in the second year they won the last game so we had 44 consecutive games losses. It set an NCAA record.

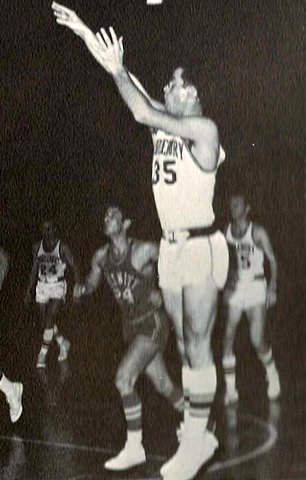

Peter Roby and his picture-perfect jump shot spent too much time on the bench in foul trouble. Roby led the country in fouls per game, depriving the camera, and his teammates, of more shots like this one.

Minton: Peter Roby, [one of our best players] led the nation in fouling. He [averaged] 4.78 fouls per game. So he sat a lot and I played. Roby would start, but he’d have two fouls with 16 minutes to go in the first half most games and I’d be in the game. And he never made it to the end. If we played 24 or 23 [games] he fouled out of 19 games.

Lindholm: I was his substitute and if he fouled out when we were ahead, we lost because I went in the game most of the time — it was a real step down.

Minton: [It was about] changing the culture from a culture of losing, to a culture of winning. When I was a senior year we won 10 games. Well, after [the varsity went] 4-18 when I was a freshman — there were no freshmen on the varsity in the late ‘60s because of the NCAA rules — and then 1-22, 1-22 … 10-14, you couldn’t believe it.

Lindholm: I think the freshman team my senior year had some really good players. So even though we had back-to-back one-victory seasons, we were getting better. I tell people all the time, the team I played on with one win was the best talent I [ever played with]. And then [Gerry] had a couple of strong classes. Some guys came in ’67 — Jim Keyes, who’s now working at the College, was a good big guy, John Flannagan, a good guard — just good players. And if you look at the scores from ’67, we scored 90 points against St. Michaels in a loss — they scored 110 or something. We averaged 77 points my senior year. We could play with teams … we just couldn’t beat them. And after Gerry left the team had a number of winning seasons. So we got competitive pretty quickly after those one-victory seasons.

Minton: When I was a sophomore we got four good guys: Gene Oliver, who could really rebound; Rich Browning who’s from the Jersey Shore — really tough, good player. Those two played as sophomores.

But that class that came in when I was a junior was Jimmy Keyes, John Flannagan, John Torrent, Barry Mathayer, Dave Kufta, John Olinowski and Lee Cartmill — all of them could play. We were clunking along my junior year and they started to play. They weren’t all basketball players but they were all good athletes. So now when we were seniors, Browning came back, Oliver was a year older, all of these guys are now sophomores and we’ve got players. We got a couple of good recruits that year and that turned the deal. That got us to 10 wins.

And then Alaimo left and Gary Walters, who’s now the AD at Princeton, came.