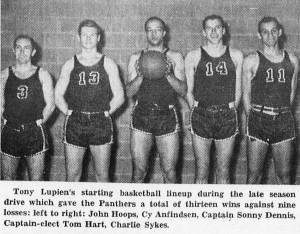

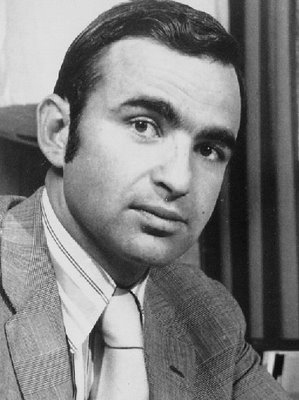

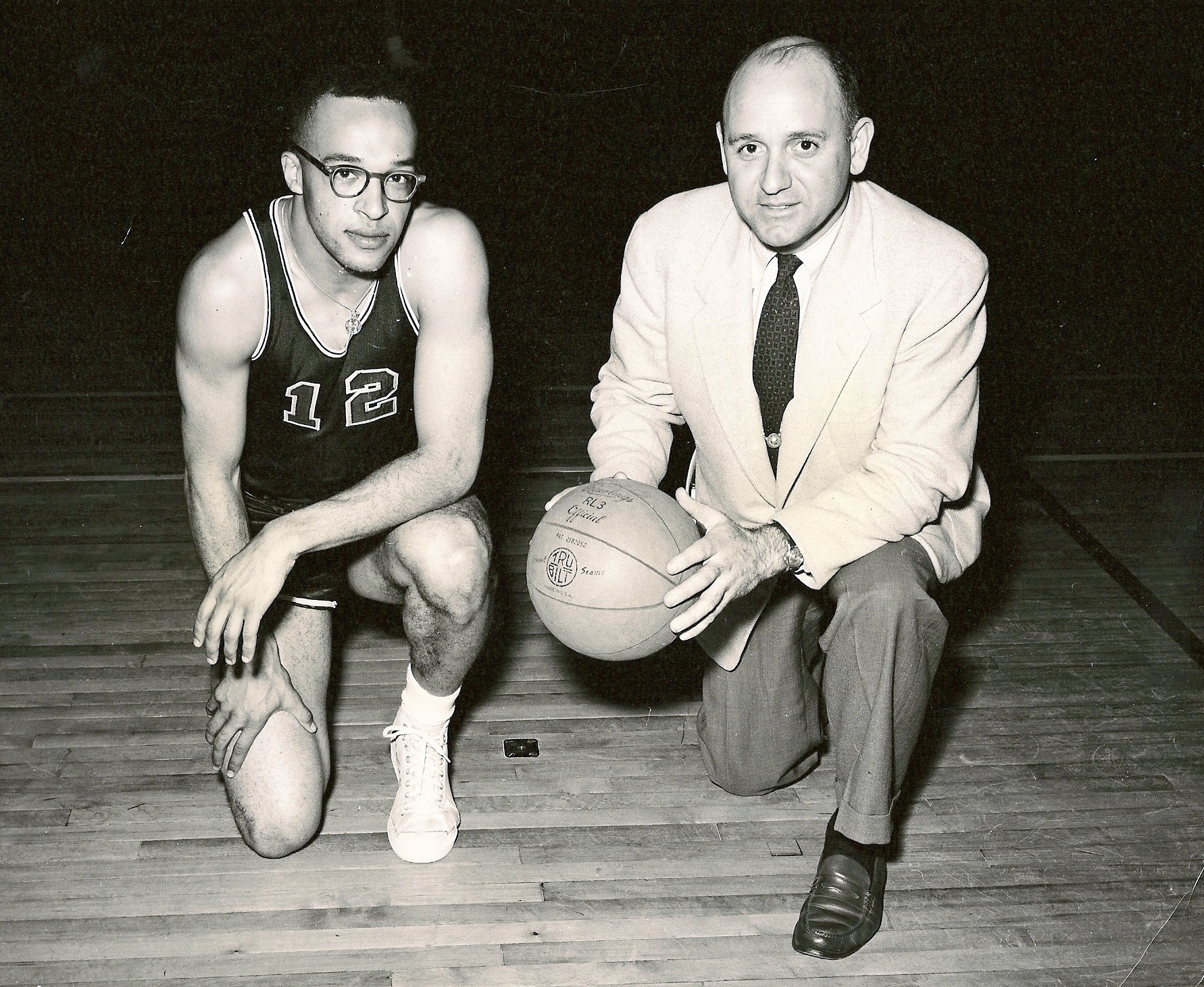

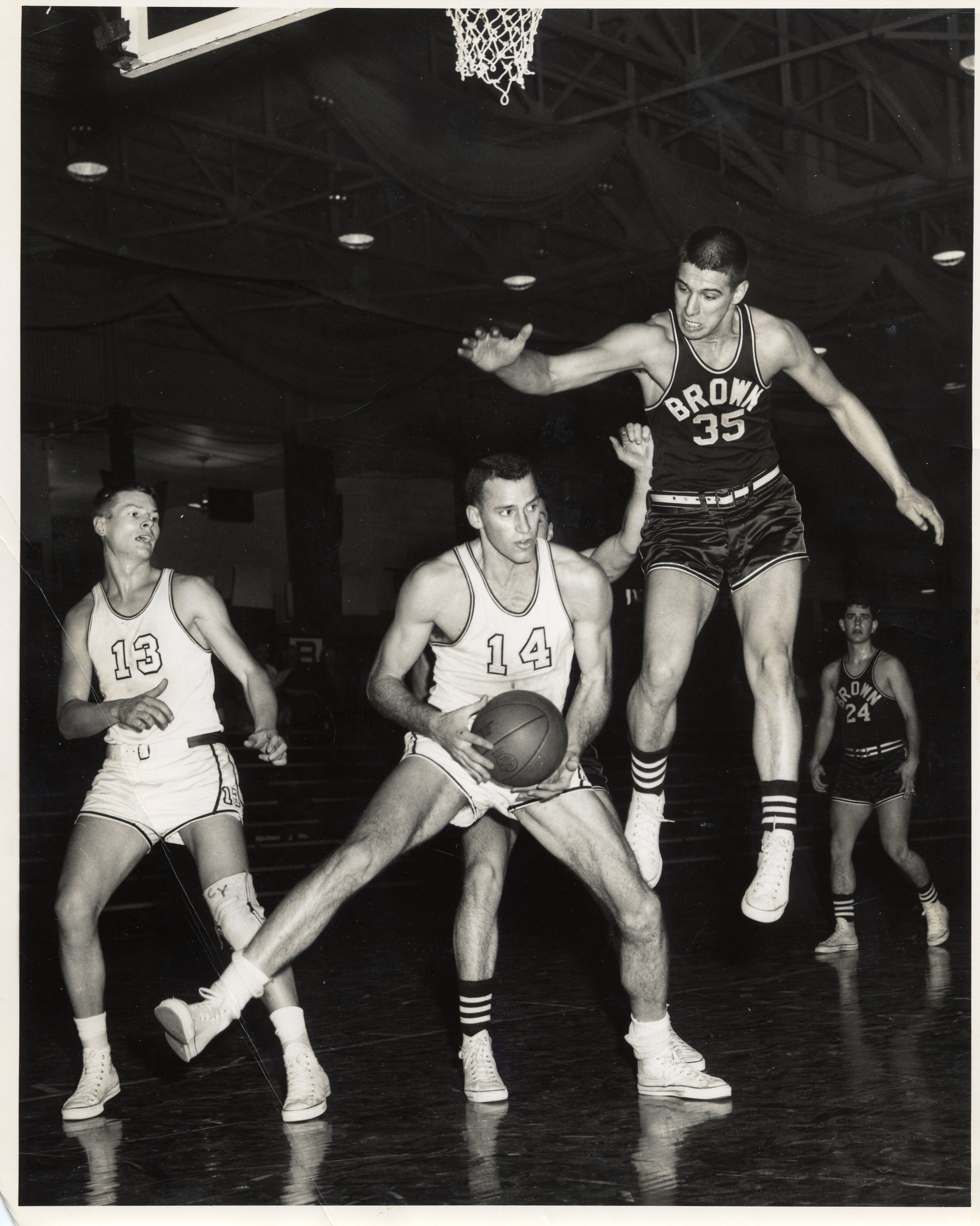

Gerry Alaimo was a breath of fresh air; he was under 30 and he had been a great basketball player at Brown. I think he was about 28 years old, big guy — about 6’4’’ or 6’5’’ — very animated, Italian. He just had such an overwhelming personality and was such a contrast to the guy who he succeeded, Stub Mackey who was a very likable guy, but his teams had been really unsuccessful.

Gerry was very charismatic but he always played up his blue-collar roots — he was an Italian kid from Torrington, Connecticut. Whenever you went and said, “I have to miss practice, Gerry, I have a test tomorrow,” he would say, “What you can’t give me an hour, you can’t give me two hours? I went to Brown and all I did was play bridge and I got through Brown.” He just wouldn’t hear it. But he really liked his players, and when he would come back later on [after he left], he would talk very fondly about everybody and how much he wished he hadn’t left after his modest success at Middlebury to go back to his Alma Mater, [which] was inevitable.

But he also treated some players terribly — he ran them off the team. He did some things that were, truth be told, unforgivable. But we really liked him.

[Gerry] had no staff and he liked us. I remember my senior year, he drove me in his car and we would go over and scout Norwich.

He lived in the dormitory in Painter Hall. He spent a lot of time at the Legion [a bar in town] drinking bear with townspeople. He had a big, enormous, powerful personality.

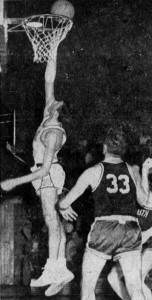

He knew we weren’t very good, so he said that we would be the best-conditioned team in the league, and I think we probably were. One day our tongues were hanging out after we had practiced for a long time and Gerry thought — and we called him Gerry — that our effort had begun to flag and somebody had been slow to dive on a lose ball. I had the ball and he said, “Roll that ball on the floor, I’ll show you how it’s done.” And he dived on the loose ball and broke his wrist. Practice was over. And you can look at one of the [old] pictures, you’ll see him with a big cast on his wrist.

We used to travel places in cars, sometimes in vans. I remember this vividly: Gerry was always quitting smoking. He hated the fact that he smoked. And so you’d be driving behind Gerry in a car or a van and you’d see this package of cigarettes flying out of the window. He quit smoking a thousand times.

He had a license plate that said NIT 73. He came here in ’64, so we were going to go to the NIT, which was even bigger than the NCAA Tournament then, in ’73. It was a joke, because teams like Middlebury didn’t go [to the NIT], but that was our goal.

He was such an impulsive guy, he was always jumping into his car and then backing into people. He got into about 10 accidents — his car was always crumpled in the rear.

I think he prepared us terrifically. It’s too bad our records were so poor, because I think he worked hard to put us in the best possible place to win.

I heard that his players called him the fruit vendor.

I don’t know why that is, that’s probably Rick [Minton]’s class. [Gerry]’s the guy who gave Rick Minton his nickname, Clubbo. He said one day that [Rick] was so slow he ran like he had a clubfoot. That got shortened to clubbo.

The freshman coach was the soccer coach, Joe Marrone. He left Middlebury and won national championships at Middlebury. But he was not a guy who was beloved by players. He didn’t know anything about basketball. We had eight or nine games and it was a real letdown from what we had experienced in high school.

[Gerry] was all alone as the varsity coach. I remember I wasn’t playing much my senior year and our record was so poor. So I went to Gerry and told him that I could beat the guy playing in front of me in one-on-one, nine times out of 10. And he said, “I believe you, Karl, but he’s a sophomore and you’re a senior, and we’re 0-11.” So I was kind of the de facto assistant coach. He knew I didn’t like not playing, so he’d say, “Come sit next to me. You’re in charge of finding out how many timeouts I have left.” He used to stand at the end of the bench when there was a problem and say, “My staff! Where’s my staff? That’s something my staff should have for me,” when he needed to know something about a game.

I used to help him with his basketball newsletters. I would proofread them and make some contributions and he showed me his letter one year. He described the different players on the team and then when he got to me he said, “Attempting to gain one of the other spots in the starting lineup is Karl Lindholm, who also plays baseball.” And I said, “That’s it? That’s the best thing you can say about me?” And he said, “Yeah, that’s a compliment. You play baseball, too!”

Four years out of college I started teaching and coaching in Cleveland. And I had been somewhat imbued by the counterculture spirit and the sports revolution of Jack Scott. So I was thinking a lot about sports and values and why kids play. And at our annual sports banquet at the school where I was teaching I got to give a little talk about sports. And then it got published in the school magazine, and it was very idealistic. I was teaching English at the time and cited different guys as sources. So I sent a copy of it off to Gerry who was coaching at Brown and I never heard anything. But he used to send me his Brown newsletters, just so I could see what he was doing. And the next year after I gave this talk I noticed in the Brown newsletter [that] my whole talk had been exempted with no acknowledgement, no credit — it was as if he had written it! And we had a boy named Michael Frasier, who eventually went to Georgetown, who was seven feet tall. And Gerry called me after he committed to Georgetown and he took me to task. He said, “What the hell are you doing? You have a seven-foot kid and you don’t call your old coach? What’s wrong with you?” So we chatted for a while, and then I said, “By the way, Gerry, I’m still a little upset about your taking this talk that I gave and using it in your newsletter and not giving me any credit!” And he didn’t back off for a minute. He said, “You should consider that a compliment; that’s flattering! I used to run an offense with you guys with three guards out. At the beginning of the game at North Carolina Dean Smith doesn’t get up and say ‘This three guard offense that I’m running and winning a national championship with … I stole it from Gerry Alaimo!’” That was his analogy for taking my piece and throwing it in his newsletter. But you couldn’t ever stay mad at him. As you can see the players from that era are very loyal to him … except for the one [or two] who hated him, and he ran them off the team.

Of all your teammates, who will you remember playing with from those days most?

Dave Nicholson.

Why?

He was ferocious. He was about 5’8’’, he was an All-American soccer player, he ran the mile in track, and he was not a blue-collar kid. But he just played so hard. I believe he invented the charge — the offensive foul — as a defensive weapon. He told me in one game they called 20 charges against the other team. On the break he would stand in front of the guy and [the refs] called it. He cared nothing about his body, he was hell-bent. He wasn’t a very good shooter but he was a fierce competitor and a very complicated, interesting guy. Ultimately he went to Vietnam and he was wounded twice in Vietnam. And he wrote a book called Tales from the ‘Nam. It talks about his life walking the point in Vietnam. He was a real risk-taker — very unusual for a place like Middlebury.

We were up playing Norwich and he took a [charge] against this big Norwich guy, their biggest player, probably a foot taller than [Nicholson] was. And the refs made no call. And as they untangled the guy got up and stepped right on Nicholson. So Nicholson, a head shorter than this guy — at Norwich, the whole cadet corps is in the building — runs down the court, turns this guy around and decks him — hits him right in the jaw with a punch and knocks him down. And there was a lot of dancing around with the benches and so forth and I thought, “We’re going to do this at Norwich?”

We had a game at Wesleyan my senior year and Gerry had already changed our schedule to improve it so that the modest number of wins we had earlier when he was here were gone. The Canadian schools we could meet were gone and replaced by powerhouses — Northeastern, AIC, Springfield and so on. We went to Wesleyan and Gerry asked all of his players for their complimentary tickets. (People used to charge for games at most schools). Because Gerry was recruiting heavily in the Hartford area cause that was his home and he had a dozen or so high school kids [coming to the game]. Well the Wesleyan coach found out about this and was unhappy that [Gerry] was using, in essence, Wesleyan money to recruit kids to Middlebury. So he said, “I’ll show them.” And Wesleyan was better than we were, but not like this. Wesleyan pressed the whole game and played only their starters and maybe a couple of subs and they beat us by 60 points, 111-51! Gerry played the end of the bench. We were probably 30 points behind at half and lost by 30 more points in the second half. And Nicholson couldn’t tolerate this so he fouled out. And there was a group of very abusive Wesleyan fans behind us. So Nicholson comes off the floor after he fouling out and these guys start really getting on him. So he gives them the finger and out of the stands comes a rubber chicken and hits him right in the chest. That was a pretty humiliating defeat. That was Gerry, he was trying to improve the program.

How about other guys who stand out?

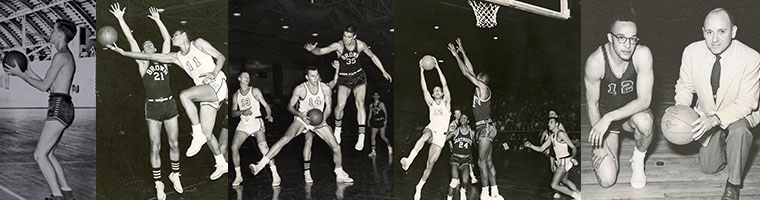

In ’66 we had a 6’7’’ kid named Charlie Ladd who was an unusual personality. He played well some nights and some nights we said, “We were all on channel 3 and he was on channel 22.” Some nights he just didn’t show up; he loved to sit in his room at the fraternity and play his clarinet. He had a couple of 30-point games, but he was a bit of a character. We called him Chaz, Chaz The Real Tall Lad.

How did Alaimo take a team that was consistently winning one game a season to winning 10 games in 1970.

I think the freshman team my senior year had some really good players. So even though we had back-to-back one-victory seasons, we were getting better. I tell people all the time, the team I played on with one win was the best talent I [ever played with]. And then [Gerry] had a couple of strong classes. Some guys came in ’67 — Jim Keyes, who’s now working at the College, was a good big guy, John Flannagan, a good guard — just good players. And if you look at the scores from ’67, we scored 90 points against St. Michaels in a loss — they scored 110 or something. We averaged 77 points my senior year. We could play with teams … we just couldn’t beat them. Our best player in my class, Peter Roby, led the nation in fouls per game. He fouled out of almost every game but maybe two or three. I was his substitute and if he fouled out when we were ahead, we lost because I went in the game most of the time — it was a real step down. Ironically, they often say “it’s darkest before the dawn.” The kids who Gerry recruited who came in ’66, ’67 and ’68 were good players. And after Gerry left the team had a number of winning seasons. So we got competitive pretty quickly after those one-victory seasons.

How did you come to choose Middlebury?

I played football, basketball and baseball in high school. And sports were not a factor in my choosing colleges. I knew wherever I went — I was going to go to a school like Bates, where my dad went — I was going to tryout for the teams. I thought in baseball and basketball I’d probably be good enough to make the team. But I don’t think I thought about it beyond that. I certainly wasn’t going to be good enough to make a difference. I came to Middlebury because I liked the whole scene. I don’t think I even knew how weak the team was.

It was a different era — I think a lot of coaches at places like Middlebury didn’t recruit at all. They just coached the kids who showed up.

It would have been nice if Gerry had spent a couple more years here because he would have seen some real benefits. Can you imagine 10-14 and that was good enough for Brown to say, “Come on home.”

What games, accolades or moments stand out from your career?

The most points I ever scored in a game in college was 14.

When did that happen?

That was against a Canadian school, St. Mary’s of Montreal. Sophomore year.

Where were you scoring from?

I could shoot. I was slow, but I could shoot.

So you would have benefited from the three-point line if it had been there?

I think so — that’s what I tell my kids. I was six feet tall, which, in those days was tall enough to be a swingman. I tell people I was too short to be a forward and too slow to be a guard. I was physical; I weighed 185 pounds and was fairly fit.

The game I actually remember the best, it was my senior year — the one-victory year — and the second or third to last game was against the University of Vermont in our gym. And we had them beat; we were ahead by five points with a minute to go. And the way I like to tell the story, I lost the game all by myself. My man scored a basket to make it three points. I took the ball out and I threw a bad pass inbounding the ball … threw it to a UVM guy who drove to the basket. I fouled him, he made the basket and the foul shot, and our five-point lead was cut out in about four seconds, all by me. But we lost to them by two points. And a win against UVM in that miserable year would have really helped salve the wounds.

We had a ton of really close games that we lost. We always played an ambitious Christmas tournament but we were always seeded number eight. We would play the first seed, the home team, for an easy win for them.

Before Gerry could change the schedule we played in Montreal. We played in the finals of that tournament and beat Sir George Williams. I remember we played the Canadian Military Royale (CMR), the Canadian military academy. They had no stands in the bleachers, guys just wandered into the gym like [it was] a pick-up game, half of them were smoking cigarettes. We beat them pretty good.

We had a lot of tough losses. I used to ask myself: was it a weakness on our part that we tried so hard to win and we couldn’t. Were we just pitiful? Should we have just taken it easier? The guys in ’65, Paul Witterman and Joe McLaughlin, joked a lot about the season and all the ways they didn’t train. We couldn’t get away with that with Gerry; we trained pretty hard — we tried hard — we just lost all the time.

Our one win was memorable — we played Brandeis at home and won by 13. They were coached by KC Jones who played for the Celtics and coached for the Celtics.

It’s probably easier to romanticize losing now than it was then. What was the culture like to be on a team that kept coming up just short?

People weren’t cruel — nobody came to the games. We’d have games where there were 200 or 300 fans … for a minute or two. They would come into the gym to get warm at the period breaks in hockey. We had one game it was right near the end — the score was tied with a minute to go, or something — and there were a lot of fans standing at the doorway to the gym watching the game, and somebody yelled, “The hockey game started up!” and they all left, and we all thought “You could stay a minute and see what happened!”

In ’64 and ’65 there was a sense that there were good players in the school not playing basketball. When I was here I didn’t think there were. I thought the best basketball players in the school were on the team. I think it was met mostly with uninterest rather than contempt or ridicule.

In the ‘60s how did athletics, and particularly basketball, fit within the academic mission of the College. And speak further about the relationship between the team and the student body.

I don’t think there was a real separation between the jocks and the non-jocks. The school was quite a bit smaller, I think we were down between 1200 and 1500 students. I know athletes were probably favored in admissions. Grades were a whole letter grade lower [and] the male enrollment was much weaker than the female enrollment academically. The average grade was between a 76 and a 78. So if the average grade was a C there were as many Fs as As, so it wasn’t hard to flunk out. I think it was a pretty integrated social atmosphere. Even though the teams were bad, playing sports at Middlebury brought you distinction and honors.

We had training rules — we didn’t drink at all during the season. And even a team like ours, we didn’t have a beer during the season, or if we did it was a very quiet thing. I was suspended one game my senior year because I went down to the Pine Room, which was the college bar underneath the Middlebury Inn with [alumni] who were [visiting]. I went to the Pine Room, and didn’t drink. The next day [Gerry] calls me in and says, “I heard you were at the Pine Room last night.” And I said, “Yeah, but I didn’t drink.” And he said, “I can’t have you at a bar. We’re having a terrible season and people see you at a bar.” So I was in street clothes for the next game. So there were some significant differences between the [athletics] stereotype and the [reality].

How has Middlebury basketball changed over the years? What’s the biggest difference today from your era?

I never imagined this level of success. It was unimaginable. I knew Russ Reilly when he was at Bates: we had mutual friends; played on the same intramural team. And then he came over to Middlebury and coached the team for 19 years. And he had overall a losing record — I contend that he played a very difficult schedule — and we were mediocre. And I thought that was about as good as it would ever get. He was 14-10 on year, and I thought I’d died and gone to heaven.

But it has just changed enormously in terms of the seriousness of the structure and the recruiting. Now we use Division I terms like “walk-on” and “recruit.” Nolan Thompson is a walk-on. We were all walk-ons! The conventional wisdom was that Middlebury would never have good basketball teams, even consistent winning teams. Tom Lawson was here for seven or eight years and I think most of his teams had winning records. And then Russ was here for [19] years and then Jeff Brown replaced him. And the first eight years I think we had two winning seasons and five losing seasons and maybe a .500 season. But I just never expected that we would be one of the top teams in the country because it was Middlebury! Middlebury was all about skiing and ice hockey. So the whole thing is different.