The Middlebury basketball program that we know today looks very different from years past. Yet despite the differences, there remains a bond between former and current student-athletes that has endured over the decades, stretching back as far as World War II. With the creation of an athletics museum in the new fieldhouse commemorating athletes, teams and events both present and past, investigating that bond, and why it still exists appeared prudent. What follows is the first series of many, in which former members of the Middlebury men’s basketball team reflect and recall what it meant to play basketball at Middlebury.

Kyle Prescott ’49: Basketball in the 40s wasn’t quite at the level that hockey was. Our home “court” was the high school court. We didn’t have the extension on the new athletics facilities — they were only built the year I graduated, in 1949. During my days at Middlebury, all our games were at the high school gym.

I was one of the trainers — water boys, whatever you call them — I was always on the bench of the basketball team. So that’s how I got to know the basketball guys well.

I was always interested in Middlebury basketball and watching the team, but they never won enough games while I was there — it was always a losing season.

Donald “Dee” Rowe ’52: I started school at the University of Rhode Island, which was then Rhode Island State College. The coach at RISC was named Frank Heany and I had wanted to play for him, and went there for school.

After my freshman year — and at that time everyone had to play freshman basketball — he retired, and a new coach took over. So I decided I wanted to transfer. I had a very dear friend, Ken Nurse, and he said that Middlebury was looking to build their basketball program. I knew nothing of Middlebury, went and visited, and fell in love with it and then transferred there.

I had to sit out a year and then prior to the first year [I could play] I broke my ankle and didn’t play for the year. That was a heartbreak. And then at the end of that year, coach [Richard] Cicollella left.

And then Middlebury hired Tony Lupien.

Part I: “[Tony] was very democratic, in the Greek sense of demos — the people. He knew the people and the people knew him.”

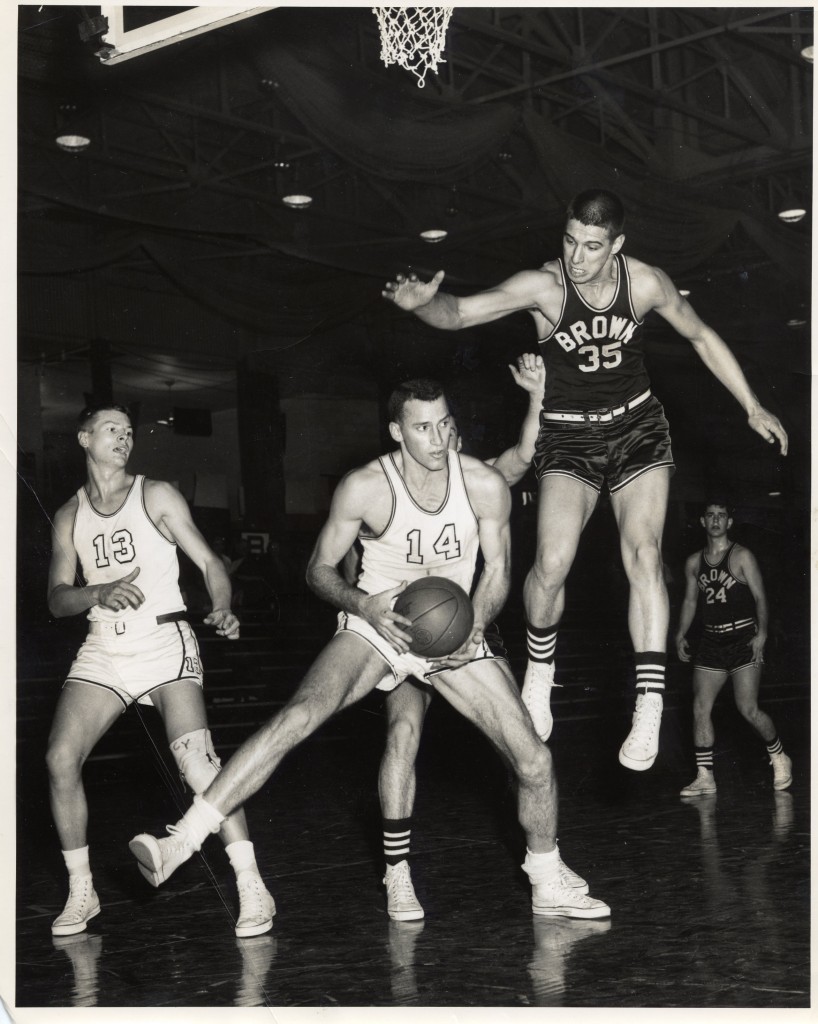

Tom Hart ’56: [Head coach Tony Lupien] was a tremendous seller of the program and a master of getting the most out of every athlete he had. He instilled a sense of pride in the team and in the school. He was just a great motivator.

Zip Rausa ’57: [Lupien] had a very positive impact all the way. He had been a professional baseball player — he was with the Boston Red Sox and a couple of other teams. So he knew all about sports and he knew the mentality of athletes. And of course he had a couple of ringers when I got there: we had Tom Hart and Sonny Dennis and then of course Charlie [Sykes].

Tony lived three hours away [from campus] and he would spend nights sleeping in the Field House. He would go home on weekends or during vacations. He was well-liked on campus and he wanted to win. Winning wasn’t everything for Tony, but it was the best thing. He was able to take those three talented guys, Sonny Dennis, Tom Hart and Charlie Sykes, and he blended it in with a couple of guards who were pretty good — Johnny Hoops was excellent — and we finally turned it around and had a winning season. Tony let those of us who were on the JV to sit on the bench during some of these games and we went down to play Dartmouth, and that to us was big time basketball. And Middlebury almost pulled off the upset of the year. I think we lost by two or three points in the last minute or so. Charlie Sykes was kind of a hero in that game.

Charles Sykes ’57: It was my freshman year and we went up to Dartmouth to play Dartmouth and we lost in overtime. It was the first away game I ever played, and it was a great game. I was matched [up] with a guy named Pete Geitner, who’s the father of the former Secretary of the Treasury, [Timothy Geitmer]. I later met [Pete] in New Dehli when I was the CARE Director in India in the early 70’s. And I didn’t let him forget that I held him to six points in that game and outscored him! It was a great game — I wish we had won it — but they were awfully good.

Rausa: [Tony made some coaching] innovations that I [haven’t] seen anywhere before or since, but that I thought they were very successful. Playing against a zone defense was kind of difficult, but Tony came up with [a new offense]. Imagine the 2-2-1 setup on the court. You’re going against the zone, you’ve got two guards [at the top], two forwards on the [wing] and the center roaming underneath [on] the baseline. So the way the play was started is the guard on the left-hand side would hit the ball hard, pass it to his other guard on the right, which was a signal for one of the forwards to dash immediately into the foul line. And then the [guard] that tossed the ball in, hurried down to become the guard on the left-hand side, so now you have a 1-3-1 setup. You would stay with that until it didn’t work for a while, and then go back to the other innovation. But that way of going from a 2-2-1 to 1-3-1 did a lot to confuse the defenses and it also gave Tom Hart and Sonny Dennis a little more operability, and of course Charlie as well. The other innovation was — and this I did get to play with the varsity in the later years… Tony would designate four guards to be chasers and he would say to us on the bench, “Go in there and give me a good two minutes.” And that’s all it was. When you went in there, your job was to run all over the backcourt trying to steal the ball and give every ounce of your energy toward that effort. He didn’t want us to handle the ball or score anything — just to harass the other team. That worked pretty well for a while.

Sykes: Lupien was a very, very interesting person. I always liked to describe him as the “Dean of Life Sciences” because he was constantly engaged and talking with the team and with individuals on the team. He himself had had a very illustrious life, having graduated from Harvard and been captain of two sports [there]. Then he joined the Boston Red Sox in 1941, I believe, and had a couple of good years with the Red Sox before he went to the Navy. But he was a very interesting person to be around because he had a sense of humor and he had these interesting tales [that] he would tell, which usually revolved around sports and stories that are passed on from generation to generation amongst those in the locker room.

Carl Scheer ’58: Tony was professional, expected you to act as a professional in terms of how you acted on and off the court, but he never pushed you beyond what was reasonable.

Sykes: He was also sort of a celebrity in New England. Everywhere we visited and had games people would recognize him — there would be shouts “Hi, Tony!” Tony knew all these people in every corner of New England, including northern New York state. Everywhere we went they would great him very warmly and vice versa. These were people who were not often professionals — [it was] the bellman at the Hartford Hotel or a gas station attendant or a locker room attendant. And we always wondered how he knew all these people. We all conjectured as to where he might have met these people and finally one day he told us, as we met a gas station attendant, we asked, “Where did you know him from, Tony?” He said, “Harvard Thirty-Four (’34).

And this would go on over and over and over again. One season we went down to Cambridge to play Harvard in a very low-scoring game. We beat Harvard that evening, and as we were leaving we heard someone say, “Hi, Tony.” And Tony turned around and said, “Hi, Jake.” And we all looked at each other and said, “Harvard, Thirty-Four!” In a way it told a story about Tony. He was very democratic, in the Greek sense of demos — the people. He knew the people and the people knew him. This was part of his character and part of his moniker, this recognition. And it might have reflected the fact that not everyone who went to Harvard, in a way he was saying, was a successful person in the corporate world, or in the government, or making their name in a variety of other fields. I guess that was the underlying message that he was sending to us. Anyway that’s what we drew [from it] — maybe we didn’t reach the right conclusion, but that’s what we thought after knowing him for several years.

Hart: One of my most outstanding remembrances was that it didn’t make any difference where we were driving to a game, we’d stop at a gas station or a convenience store and everybody knew Tony, no matter where we were. Even in the arctic tundra of extreme northern New York state we would stop at some little gas station and the owner would come out and give him a hug and say, “How ya been, Tony?” It was unbelievable.

Sykes: There are so many [great stories about Tony]! I think one of the funniest ones [was] he had invited us all to his house and had prepared a great big meal — spaghetti and meatballs. He had been working on the spaghetti and meatballs all day and we were enjoying it, and he was telling us this story. He said, “I like all of you guys, but I’ll tell you one thing: you know I have four daughters, but I would never think of any of you if you walked down the street with your sports bag and your tennis shoes over you shoulder. You wouldn’t be eligible to go out with one of my daughters — I just don’t trust you athletes.” [He said this] with a big smile on his face, of course, afterwards. And we did meet his daughters and they were delightful and very much loved their father and held him in great esteem. As we did.

Rausa: Tony was easy to get along with. He knew he had a couple of major stars in Charlie, Sonny and Tom Hart. And the only one who really gave Tony any trouble — and it wasn’t any real trouble — was Tom Hart. Tom Hart was the nation’s leading rebounder. I’ll never forget the game … I was sitting at the end of the bench. Tony wanted Tom Hart to rebound and put the ball back in or just rebound — he didn’t want Tom to shoot from anywhere other than close in. I could tell that [Tom] was itching to shoot some one-hander from, oh, about the 15-foot mark from the basket. It was almost like watching a slow-motion movie: you could see Tom — he got a rebound and he dribbled it back out, just outside the top of the key, and Tony, who had a very deep, baritone voice, could sense that Hart was going to throw up a long, one-hander. So he started repeatedly saying, “Don’t do it, Tom. Don’t do it.” Well Hart threw it up, and it swished through the basket. Tony was irritated and looked at us down the bench and said, “I don’t care if that ball went in or not, he was not to take that shot.” Well we got a pretty good laugh out of that, and it didn’t happen more than once. He was a great organizer, very smart guy and I don’t think I ever saw him lose his temper genuinely.

Hart: I was all geared up to take a 15-foot hook shot, and I hear from the bench, “Don’t do it, Tom!” [Laughs] I just remember worrying about getting pulled from the game because I took the shot.

Rowe: Sonny Dennis came back to speak at a function that we had for Tony, and made some comment about Tony that was as great a compliment to a coach as I’ve ever heard. I’ll just never forget it — there was a tremendous amount of love.

Part II: “I wish they had some movies of the old games, just to watch Sonny Dennis run.”

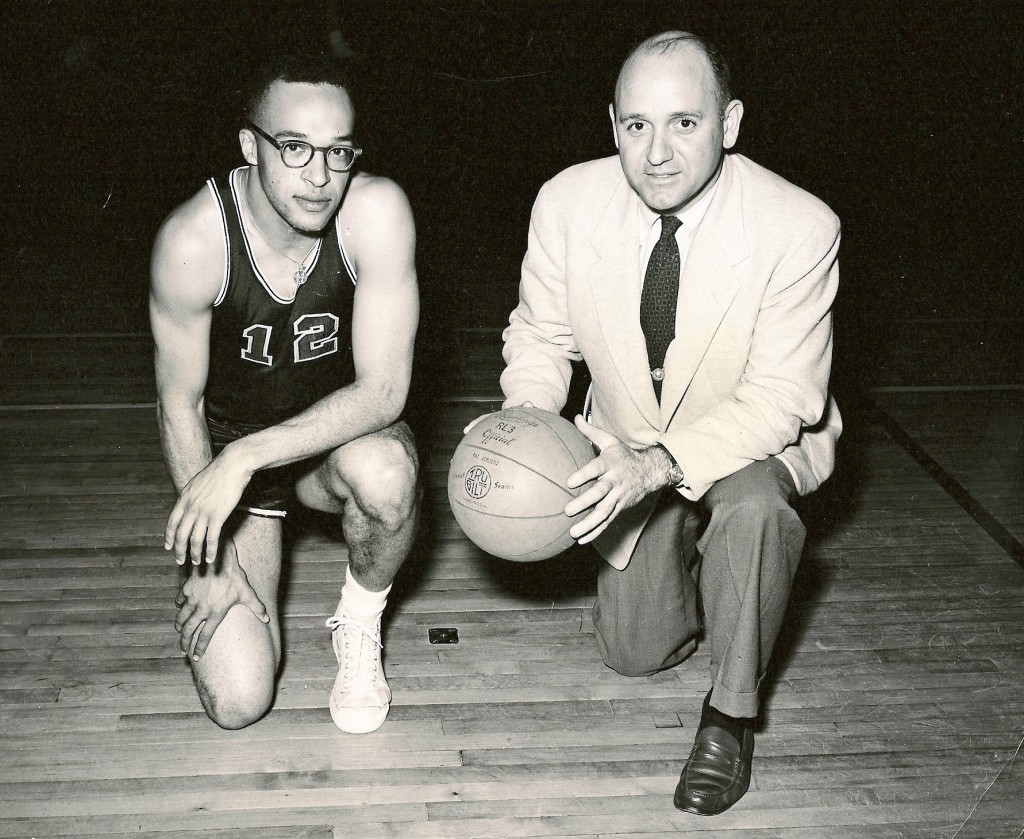

Rowe: Maybe the best athlete of our time was a kid named Alfred “Sonny” Dennis ’55. He played football, basketball and track. He was African-American. There weren’t many African-Americans at that time.

Hart: Sonny was there a year before me [in 1951], and his presence his freshman year brought a lot more interest than Middlebury ever paid to the basketball [team]. So through him they developed a following, I got there a year later, and had a fair amount of success my freshman year. All of a sudden the stands were getting filled and the cheering was almost raucous — it was quite a transformation.

Sykes: [During my freshman year] we would go out on the court and there wouldn’t be anyone in the stands at all, maybe 30 or 40 people. But it was interesting, in successive years there were more students, more towns people and faculty coming to watch the [basketball] games than the hockey games, which was unusual, because we could never compete with hockey in terms of attendance during [my] first year. But we started a winning streak and you could see the people ducking out of the hockey game and come over and watch the basketball!

Rausa: I wish they had some movies of the old games, just to watch Sonny Dennis run. He ran like a deer — he had huge, muscular thighs, but his calves were narrow — I never could understand that. He could drive, he could break some tackles, but if you got him in the open field you were never going to catch him. He was a marvel to watch.

Rowe: Tom was a great player; he was an even better player than Sonny.

Skyes: Tom was a spectacular jumper. In track and field he high-jumped and also broad-jumped. He had this remarkable ability to get up above the rim at a time when dunking was discouraged, in fact I think Tony would have pulled anybody out of the game if they had tried to dunk the ball. But Tom was able to set such spectacular statistics in the rebounding game that I think are just incredible.

Rausa: I think Tom was only 6’4’’, but he had enormous arms. You know when you go to Marineland and the attendant holds out a piece of fish for the dolphin and it jumps up and grabs it? That’s what it looked like whenever [Tom Hart] went up for a rebound: he just went way up high and came back down.

Scheer: I sat out a year [after transferring] and in the year I sat out Middlebury had a very good team. Tom Hart played center and was the leading rebounder in the country at the time.

Sykes: Unfortunately Tom missed a season in which he and Sonny would have played together again. And unquestionably when they were together it was just magical what they could do in terms of scoring and rebounding and how superior there play was to anyone else. In many ways the record seasons that they assisted at that time were attributable to their being together. When they were together it was spectacular.