In its fourth year, JSSL incorporates a new reflection resource and deepens a powerful oral history component. In this first of two JSSL posts, students share what they learned from their immersive four weeks that recently wrapped up in Japan.

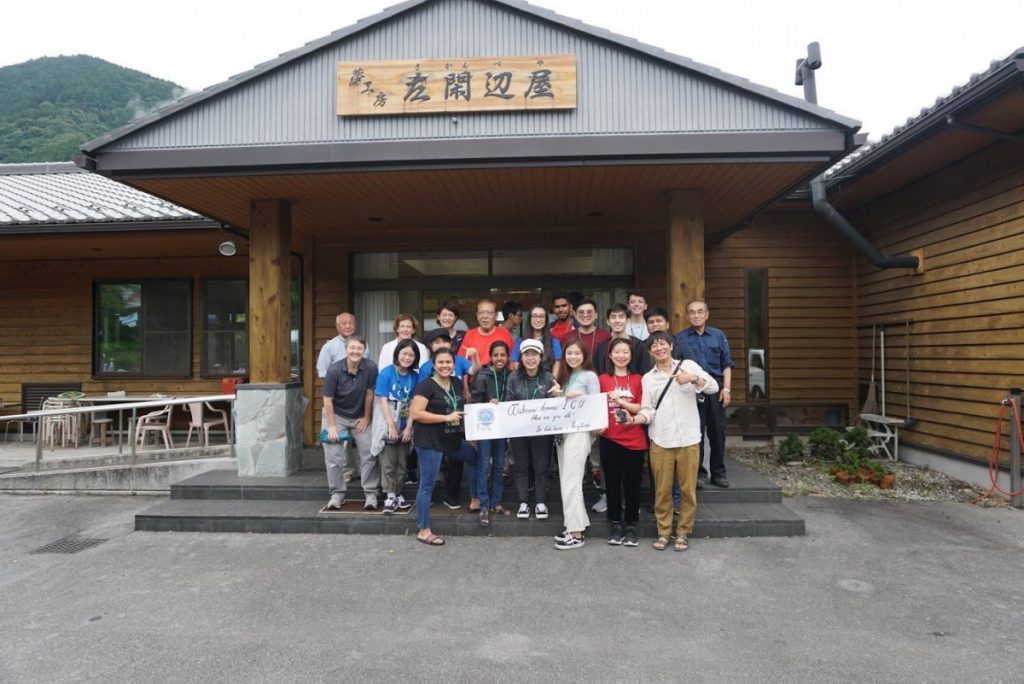

The Japan Summer Service Learning Program allows students from Middlebury, International Christian University (ICU), and member universities of the Service-Learning Asia Network to work and learn collaboratively with residents in the Tokyo area and in the rural Tenryumura. This year’s cohort spent July in Japan participating in four phases of the program: orientation, service and learning in Mitaka, service and learning in Tenryumura, and wrap-up and evaluation. Middlebury’s Center for Community Engagement (CCE) serves as one of the co-administrators of the program—Kristen Mullins, a CCE staff member, works directly with the students each summer. The Middlebury School in Japan and the Service Learning Center at International Christian University (ICU) in Mitaka, Japan also co-administer the program alongside the CCE.

Reflection is woven into the program, to help illuminate meaning in the many hands-on experiences gained during the four weeks. This year, students reflected on how the intercultural experience impacted them as participants in this program using the new Middlebury Experiential Learning Life Cycle (ELLC) hub website. This is a new reflection resource that educators across Middlebury College created together to support students across different immersive learning experiences to reflect on their learning.

Below are three reflections from JSSL participants Xiaoyu Wu ’22, Brenda Martinez ’22, and Sam Hernandez ’22 about the oral history component of the JSSL experience, a part of the program deepened by partnerships with Middlebury College’s Japanese Studies faculty.

Xiaoyu Wu ’22:

My name is Xiaoyu, and I am a participant in a summer program called JSSL (Japan Summer Service Learning). This program lasts for one month and provides participants the opportunity to experience urban and rural life of Japan. I enjoyed every minute of this program, but the thing that gave me the strongest impact was the monument of Chinese soldiers, which I saw in a rural village (Tenryu Village) in Japan.

Sometimes I wonder why I am doing volunteer services in Japan while my own country needs help. The answer became clear after my journey to Tenryu Village. There were a lot of tragic stories in this village during WWII— Families broke apart because of the war; foreign soldiers and prisoners of war were forced to participate in the construction of the dam. When Kawakami san was giving this speech about the local history, I felt a mix of conflicted feelings— Anger, unfamiliarity, frustration… Why do we have to uncover the scars of the past again? The purpose is not to re-trigger the hatred but to remember the war, just as Kawakami san mentioned in his speech, “悲劇を忘れないように語り継、この事実を後世に伝えるのも我々の役目かなと思っています (I think we should not forget the tragedy, and it is our role to convey the story to the future generations).”

There are indeed a lot of stereotypes exist between China and Japan, and it is our mission, the younger generations’ responsibility, to rediscover the good in humanity and break down these stereotypes. Because many people do not know that when forced labors were suffering, villagers shared their limited resources with them. Even after the war, there is a Japanese lady who places flowers in front of the monument every day for over 50 years.

Brenda Martinez ’22:

My name is Brenda Martinez and I am a rising sophomore at Middlebury College. Through the Japanese Summer Service Learning Program, I have learned about the Mitaka and Tenryūmura community and they have learned about Mexican-American culture through volunteer service. However, one challenge that presented itself every time I interacted with either the Mitaka or Tenryumura community was the language and cultural barrier.

Since arriving in Japan, I was alert to everything and everyone around me during the day. I had to adjust to the social norms in Japan because I do not want to stand out. I sometimes felt the pressure of having to do things “normally” because I feel like I may be representing Americans/Mexicans to them and would not like them to form stereotypes based on my actions. I realized that I even exhibited the symptoms of culture shock. I felt the exhaustion from being alert and observant anytime I was outside my room. When I was at a place where people only spoke Japanese, I left exhausted after listening attentively to what they said in order to try to understand. I feel like I shouldn’t have been as hard on myself because it was my first time being in Japan. I shouldn’t have felt forced to adjust perfectly to the environment over the course of a week.

Although I can understand and speak some Japanese, my Japanese can sometimes be hard to understand and I have had to repeat myself or ask for a translator when I do not know how to say something in Japanese. However, there were not always bilingual people around me and the process of translating can be problematic for communicating because the time in between interpretations can make the flow of a conversation less natural. Despite these barriers, the children at ちQ人, an elementary school, were so nice and understood that we were not familiar with the language or culture. When I was playing games with them, they would go easy on me or try to change the game in order for me to better understand. I am also grateful that my host parents in Tenryūmura were patient with me as I tried to communicate with them in Japanese and would use hand motions to help me understand. I am honestly thankful to everyone I have worked with because they were willing to teach and learn from me despite our language and cultural barrier.

Sam Hernandez ’22:

Hello, I’m Sam Hernandez and I am a participant in the Japanese Summer Service Learning program. During the month of July, me and an international team of students set out to participate in various service projects throughout the city of Mitaka and the rural Tenryū village. Something that has pleasantly surprised me about this experience was how easy it has been to work with people from various different cultures in a country where we are foreigners to make a difference in people’s lives.

While I say it has been easy, that means relatively. We have worked incredibly hard as a group and put in a lot of effort. But the reward we get, the memories, the experiences, the connections, they’re all so incredibly valuable that having to put in some effort is nothing. The benefits to this program will be lifelong. Not only that, but we have done meaningful service as well. The benefits for those we served are hopefully even more meaningful. Essentially, I learned that it doesn’t take much to make a difference. Whether it be helping your members make paper at a service center or pulling up ragweed in a park. Even just listening to an elderly citizen recount their youth and most valuable memories. We made an impact together as a team of various people from different backgrounds, beliefs, ideals, and goals. In only a month, we became friends. Our differences were embraced and welcomed. It was a most pleasant surprise.