by Andriiana Ilkiv, Fall 2021

Interspersed with “nothing really happened,” “what was the point?”, and “it could’ve been shorter,” the soundtrack beneath my walk out of the local movie theater in September 2019 consisted of groaning and yawning noises. We had just spent an underwhelming three hours motionless in a dark room, disappointing given we’d just watched a new Tarantino film! It was not supposed to be a European arthouse feature or an enigmatic A24 experiment, with their underlying expectation that the masses will not understand. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood forgot to be the piece of art that pleases the crowds. It forgot to really entertain. Commonly described as a tribute to the art of cinema, its history, and the Golden Age of Hollywood, Tarantino’s highly beloved film era, OUATIH captures its director’s wish to encapsulate the iconic image of the epicenter of movie making and its blooming energy in the transitional state as a result of big shifts in American culture coming along with the end of Vietnam war, the women’s movement, and countercultural phenomena. But, paradoxically enough, along with functioning as a “love letter” to cinema, the film, at first sight, seems to forget to do exactly what turned Hollywood into the modern-world marvel and the most profitable industry in the world. Does OUATIH really capture the essence of Hollywood and filmmaking, if a lot of its viewers are left confused, frustrated, and angry (in some cases, at themselves)? Most definitely. It understands it so well that it can afford to boast and revel in its cinematic excellence, by fascinating others and even making them feel special for having that sentiment.

OUATIH’s higher purpose, self-conscious style, and a unique story make me associate it with the decade of “impure cinema” (Horwath), the 1970s films concerned with all those things. It makes sense considering that without the 1970s influence, Tarantino “could not have come into being” (Elsaesser). Globally grossing more than 200 million dollars and hailed as “one of the most successful films of all time about Hollywood” (McClintock), OUATIH also has some of the most mixed reviews in Tarantino’s filmography. And the film seems to intentionally create this divide in our responses by appealing only to a select audience. As an entranced high-schooler with big ambitions and lack of real cinematic knowledge, I naively anticipated the mystery of Hollywood to be untangled and its world exposed throughout the movie. To my disappointment, OUATIH refused to fulfill my expectations, as it seemed to intentionally distance itself from those like me – at that time, a novice to the world of cinema. The film’s high caliber is something for artists to reach for, but one’s understanding why it is so will really make them feel special. I definitely cannot claim to be in the film’s favor yet but, at least, I can see why I could not fully enjoy it two years ago.

Similarly to the illusory image of Hollywood, Tarantino’s ninth film is like a world to be observed through a golden colored window. Brimming with glamor and radiance, the movie capital dazzles with its sunshine and city lights, glitter and shimmer of swimming pools. It is not open to everybody, though. Its world, presumably filled with fame, wealth, silk and martini, is shiny, elegant, and exclusive. But both the image of Hollywood and OUATIH draw a clear line between the aura of their own brilliance and those who do not deserve it (yet?) much like upscale nightclub bouncers treat the crowd. In OUATIH’s case, an average citizen would exit the theater dissatisfied with what they just watched, but a cinephile wouldn’t. Almost like observing the land of the Wizard of Oz through emerald glasses, the world of OUATIH compels us to look at it through the golden lens. If Dorothy, however, had the chance to participate, we are only observers, watching the Hollywood glory and art of cinema unravel on their own, feeling like an outsider because the scenes of our reality are not necessarily color-coded. “Occasionally tedious” but “constantly awe-inspiring,” (Hooton), OUATIH has done a fantastic job at favoring some audiences over others. With this selectivity being a possible major cause for the mixed responses, it requires one to be more than part of the ordinary crowd to be able to appreciate all of its magnificence.

Set in the year of 1969, the almost three-hour-long OUATIH presents a collection of moments in the lives of an aged western actor Rick Dalton, his best friend and stunt double with questionable past Cliff Booth, and the rising movie star Sharon Tate, all of whom, on one fatal night, are brought together by an experience beyond a Hollywood set. The obvious appeals –Leonardo DiCaprio, Brad Pitt, Margot Robbie, and, of the same if not higher significance, Tarantino’s big name immediately associated with truly unique work, almost a genre of its own, immediately sets high dramatic expectations. The film, however, early on teaches us to move from one anticlimactic scene to another free from anticipation. To put it in perspective, one major plotline’s inciting incident – Cliff discovering that the hippie hitchhiker lives at the Spahn ranch – occurs at the 1:21:49 mark of the three-hour-long film.

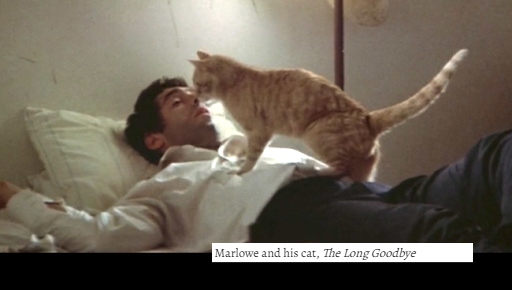

Thus, the movie’s visual style and mise-en-scène often end up drawing more attention to themselves than the plot, implying that, perhaps, the true narrative is developing someplace else, beneath our level of sensory or intellectual perception. In the world of OUATIH, the lack of dramatic tensions in the plot that more so resembles a collection of scenes with little causality and few climactic points is compensated with allusions that might contribute to one’s enjoyment of the film when the surface-level story gets too monotonous to watch. Thus, the prolonged scenes of Cliff’s meticulous feeding and petting of his dog could not only be attributed to how this loyalty gets rewarded in the end, when Brandy, on her owner’s slightest signal, gives rise to a ferocious battle with the house intruders. Functioning as a possible reference to The Long Goodbye, a 1973 neo-noir which shares many thematic parallels with OUATIH, the emphasis on the nature of Cliff’s relationship with his dog (especially that when the owner is too high to properly feed his pet) mimics in many ways the way in which the protagonist of Robert Altman’s film interacts with his cat.

The dizzying abundance of more straightforward visual cues (mostly film posters) as part of the mise-en-scène undoubtedly adds to the sense of nostalgia nurtured by Tarantino throughout the film, but our lack of understanding of what those movies might mean in the context of a scene only expands the film-viewer distance. One article dedicated to references in OUATIH on The Quentin Tarantino Archives page, a Tarantino Wiki Internet community, lists more than 70 TV and film intertextual references, as well as a decent number of allusions to venues, people, books and magazines. If we knew, like Vulture, that the poster of The Mercenary, which Sharon passes in the film theater, is an homage to its composer Ennio Morricone who also wrote the Oscar-winning soundtrack for Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight, would our overall sense of the narrative development be enriched in the same way that the posters in Robert Altman’s The Player guide the plot? Is there a higher purpose to the parallel between the bookstore Sharon visits and The Big Sleep other than Tarantino’s extreme dedication to details as a way to pay tribute to great filmmakers of the past? Will the levels of dramatic intensity drastically shift if we recognize that, as Den of Geek points out, the scene of Rick and Jay walking into Sharon’s house is comparable to the ending of an all-time classic Casablanca? Probably not. But would we gain a deeper insight into the director’s psyche? Definitely. By being able to decode the elements of mise-en-scène and dialogue we would not only understand how they tie into the bigger picture of Hollywood history, its most prominent filmmakers, and Tarantino’s evocation of nostalgia for the lost Golden Age of Hollywood; we would, first and foremost, be able to feel singled out by the film, feel like a truly savvy viewer, and be more satisfied with the act of watching itself even when the plot seems to enter its most passive points. Because these allusions do not have an outstanding impact on the surface narrative, an audience member capable of catching those references, gets to experience a deeper connection with the film as opposed to getting confused and, perhaps, eventually bored.

The film cleverly chooses who to grant its special access to, and it is not a mass audience member. Apart from being a true cinephile, it is also important to be familiar with Tarantino’s art to nourish some connection with the film. The flashback of Rick burning Nazis with a flamethrower on a film set, later vaguely recreated in the pool scene as a final strike against hippies, is evocative of the iconic Inglourious Basterds sequence of the Nazis burning in the theatre (also starring Brad Pitt). Comparing the shots will really ring the bell for someone who has seen both movies. The Red Apple cigarettes, an essential prop in Kill Bill Vol. 1, and a frequent point of dialogue in From Dusk Till Dawn, Pulp Fiction and The Hateful Eight, are branded as a sponsor for the Westerns Rick starred in, once again immediately suggesting Tarantino’s celebratory tone towards his own filmography (Crow). It seems like he is placing his films in the same plane as the period- and genre-defining pieces (Casablanca, The Maltese Falcon, and 2001: A Space Odyssey, to name a few of those referenced in OUATIH) of the last century. The author’s persona, known in the film and showbiz world for his conceit, shines through when Tarantino places the references to his works alongside the canons of American cinema, thus implying their similar level of grandeur and important future or present implications in the context of film history in general.

The strong presence of the author extends far beyond that. Tarantino’s signature enlivening of historical events, figures, and even entire periods with an ultimate purpose of revising them (e.g. Django Unchained, Inglourious Basterds), plays a huge part in OUATIH’s narrative, and adds to the further proclamation of its “otherness” from the regular audience members’ tastes. This time, Tarantino chooses to bring to life and inevitably re-imagine the transitional times between the Classic Hollywood period, also known as its Golden Age, and the New Hollywood era that went hand in hand with the big cultural changes. In the midst of the Vietnam war, the late 60s California was marked by the rapid establishment and spread of the hippie communes. Some “young people began to build new enterprises, new institutions…and new practices” (Farber, 409), which, apart from being a powerful positive force in promoting progressive social changes, have also gained notoriety as the myriads of dubious cults took over what was first a revolutionary scene. One of the multiple murders in the area of Los Angeles committed by the Manson Family cult members was that of pregnant Sharon Tate and four others in her house. Luckily, Tarantino’s universe spares Sharon the horror of that fatal night of August 1969. The terrifying post-fight views of the defeated characters (highly satirized Mansons led by “Tex” in this case), characteristic of Tarantino’s fight sequences, are a result of a successful and extra violent counterattack, orchestrated by Cliff on LSD, his loyal but merciless dog, and the combination of Rick, eight whiskey sours and his flamethrower. All of this happens in the final twenty minutes of the three-hour-long movie. The characters in opposition are forced to face each other, connected spatially and sharing appropriate motivations, to help Tarantino revise the horrible fate of Sharon, Polanski, and their friends. After two hours of leaping from one anticlimactic event to another, we are finally treated with a dynamic, hilarious sequence which, with its quick cuts and frenetic energy, contrasts with the lengthy, relaxed scenes of Sharon enjoying her time at a Playboy’s mansion party and the movie theater or Rick reminiscing his glorious acting past.

Once the voice-over narration and the graphics as time markers appear, we enter the familiar “Tarantinoverse” and “away we go,” to quote Cliff as he lights up his acid-dipped cigarette, thus foreshadowing the long-anticipated dramatic movement. Cliff’s line, originally delivered in Tarantino’s own film Jackie Brown, labeled by many amateur reviewers as the most straightforward, slow-paced, and “simply boring” (McGrath) one of his works, marks the shift in the similarly passive mood within the diegesis of OUATIH. This quote is more than just another intertextual reference – it is Tarantino’s way of saying: “get ready.” We end up gratified, taking odd comfort in Cliff bashing the ginger hippie’s head into different surfaces exactly twelve times in a row, ludicrous amounts of shrieks and cursing, and the iconic beer can toss that can be watched on repeat forever. Absurd as it is in its monstrosity, the scene provides everything we have been waiting for – fast action, hilarious dialogue, and brilliant acting, which comprise layers and layers of comedy. Tarantino finally treats us with what would entertain an average audience member – the “familiar” – although it comes at the expense of probably checking our phones for the first two hours of the film. This behavior, however, can be justified – the film’s main goal never seemed to please someone unable to enjoy an unconventional storytelling formula.

In order to grasp all of the film’s grandeur, one should love the entirety of it, including the lengthy Spahn ranch scene, through which the film fully affirms its contemptuous tone towards hippies as a whole. The main villain in Rick’s and Cliff’s lives seems to be time, the irresistible power which favors the impending industrial change rather than Rick’s dying acting abilities and an undiagnosed bipolar disorder (Vanity Fair, 12:55-13:07) or Cliff’s dubious past. But by positioning the hippie commune as a fully antagonistic force in the film, Tarantino can both express resentment at Sharon’s murder by the Manson family members, and further cultivate the nostalgia for the dying glory of Hollywood’s Golden Age, which blossomed in the times before big cultural, social, economic shifts began affecting the industry in an irreversible way. The filthy invasion of the hippies into the ranch, a typical setting of a Western, is now nothing more than “the ruins of old Hollywood” (Guinn). The good Western hero, Cliff, arrives only to discover the ranch’s old owner in an almost vegetative state, blind in both literal and metaphoric senses to the filthy systems around him. Reduced in their lifestyle to animals, the new ranch inhabitants are similar to the New Hollywood executives that completely lost themselves in the materialistic mindset of the entertainment industry.

“A time of plenty and a time of protest” (Duncan), the 1960s are marked as the first years of extensive use and general acceptance of the truly mind-altering drugs such as LSD and marijuana (Gerald, 127), and this part of the period’s aesthetic was brilliantly employed by Tarantino as an important narrative element, which further juxtaposes Cliff and the hippies. The film gives two distinctly different undertones to the drug use of two opposing forces. Cliff’s wobbling naivety while smoking the LSD cigarette contrasts with the drug-induced psychopathic tendencies and manic intentions of the Mansons. The dark ideologies of the Mansons’ cult among others are placed in opposition to Cliff and Sharon, much like the demanding, revolutionary film executives who accelerated Rick’s downfall. Consciously attempting to uncover the layers of symbolism present throughout the film is another way for a bored viewer to deal with its slow pace and straightforward nature of the narrative. Not everybody in the audience will be able to do it, though, even if they are familiar with Tarantino’s characteristic use of heavy subtext in dialogue or hidden metaphors in settings and actions. Nevertheless, it seems as if Tarantino is almost mad at the cultural shift that occurred on the brink of the new era, closely associated with the evolution of television and the blockbusters’ takeover of the majority of film production. And, whilst unable to bring back the past Hollywood glory, the director decides to rewrite the story of one rising star in the myriad of others.

The film’s, and dare I say Tarantino’s, warm tone towards Sharon’s character shines through the youthful scenes in which she is the center of attention. She revels in the rays of sunshine during the day and the neon lights at night, so high-spirited and alive. Not only are Sharon’s exuberance, talent, and ambition are revived when Tarantino gives the young actress another chance, a chance to experience Hollywood in all its magnificence. He, once again, reminds us of his authorial presence by revising history. This time, though, the twisted take on the past has a much narrower focus than, for instance, the story of slave empowerment in Django Unchained or an alternate WW2 finale in Inglourious Basterds. By giving Rick, Cliff, Francesca and Brandy the appropriate power to mercilessly slay the three Mansons who dared to disrupt their peaceful night, exemplary of that affluence and security that the Hollywood image presents, Tarantino prevents the assassination of a pregnant actress and her friends, let alone a series of homicides in one country’s cult chronicles. Perhaps, he even assumes a parallel between a tragic incident in Hollywood’s history and the big milestones of the past that shaped our contemporary world.

A viewer outside the United States, though, would have a hard time coming to such a conclusion. With his unconventional but still appealing style, and his dorky but incredibly talented persona, Tarantino has been able to develop a “film God”, “top director of all times” kind-of appeal both in the United States and internationally. Even if his films mostly deal with American history and culture, they are and will be watched by the audiences all around the world merely for the reason that he is, according to the great Peter Bogdanovich, “the single most influential director of his generation” (Copeland). As a non-American viewer, I felt, however, that with his ninth feature, Tarantino wants his audiences to be American. Moreover, if his generally enjoyable films require an average level of intellect, this one is hard to appreciate without a refined cinema taste. He admits himself, “sophisticated audiences are not a problem. Dumb audiences are a problem” (Brown). Am I, then, part of the issue because I lack everyday knowledge of late 1960s American crime history, or because I should have grown up here to know?

Apparently, the immersion into the culture would not help much – a decent part of American viewers did not understand what happened either, as these tweets embedded into a DailyDot article suggest. Here is when the film’s (this time, impossible to separate from its director’s) need to distance itself from an ordinary viewer vividly manifests itself again. Considering the centrality of the true story to the film, it is surprising that OUATIH provides us with virtually zero context on the Manson family murders. The key to understanding the murder scene’s real value—other than pure entertainment and Tarantino being truthful to his fascinating use of violent representations—would be the awareness of the Manson cult’s orchestration of multiple killings, the most famous one being that of pregnant Sharon Tate and four others in her house on Cielo Drive. Now, with this piece of knowledge only, @MarshallLeigh would have an easier time justifying, for example, the large amounts of screen time that is given to Sharon, disproportionate to the plotlines, like that of Rick’s downfall. At first, the average audiences were detached from the film based on their level of cinephilia. Are we now separated from both the movie and other, more lucky viewers, in accordance with our historical knowledge or nationality? Either way, OUATIH says, “if you aren’t knowledgeable, or at least American, I don’t want you to watch me. You’ll wonder why I’m giving so much attention to Margot Robbie watching herself act.” Or why a bunch of drugged teenagers play such an important role in the stories of a retiring cinema star and his sidekick. The film further spreading its superiority over very specific demographics might feel very frustrating because it does not try to justify itself. Some of us are just not qualified enough to enjoy the film: those without a sophisticated taste, a.k.a that of a “Tarantino movie” as a genre in itself, and specific contextual knowledge do not, therefore, deserve to know. Like a bad teacher, OUATIH prefers to stay detached from answering questions that it deems stupid. But, unlike a bad teacher, OUATIH makes this technique work to an enlightening effect – by finding out the answers on their own, a curious viewer will get closer to trespassing their “averageness” and nurturing a more intimate connection with the film.

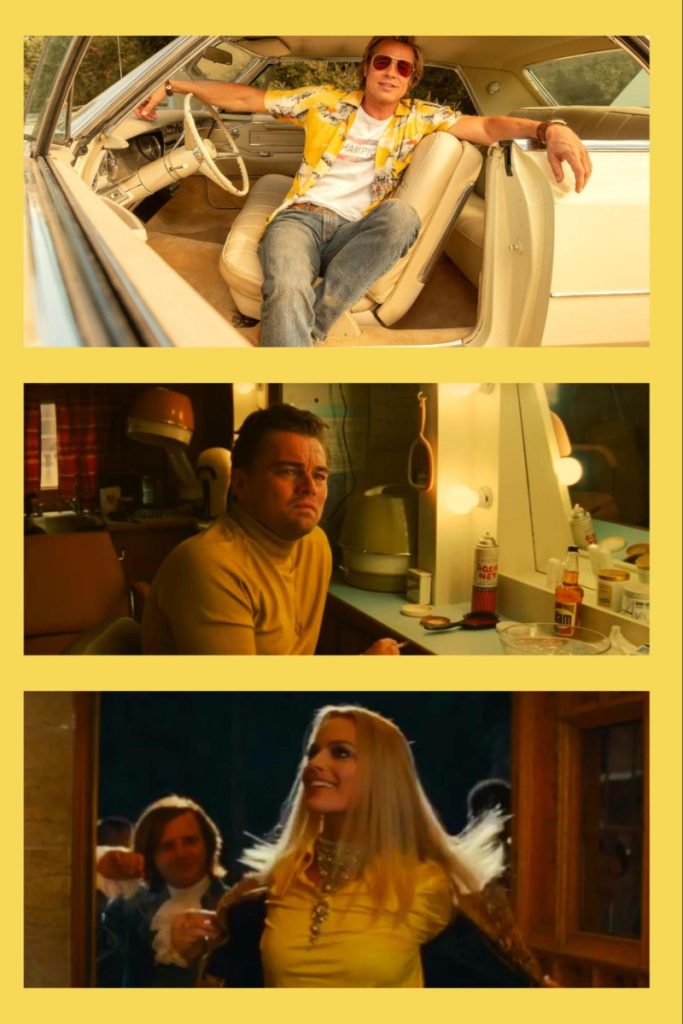

Its undeniable cinematic greatness is further projected through Tarantino’s use of the color palette, which consists of mostly yellow shades and golden tints, often associated with high class, elegance, prestige. Think of Leonardo DiCaprio in his iconic yellow turtleneck or Margo Robbie’s disco costume – all in the background of the sunny valleys of Los Angeles and sandy sets of the fictional westerns. Cliff’s memorable Hawaiian shirt is always an eye catcher, and a yellow spot will often appear even in an otherwise dark shot, like the hippies’ car in the pitch black alley. As if the assumed intellectual film-viewer separation was not enough, the film tries to distance itself visually, too. It is elevated on a golden platform as a winner of some imaginary competition, and, by creating this impenetrable wall of wealth and sparkle, it suggests its own prestige – it is set in Hollywood, it is about Hollywood, it is Hollywood. No surprise OUATIH is said to be a tribute to its Golden Age in particular – the time when it was truly majestic, blooming with life and opulence. Combined with the costume and set design, increased lighting brilliance used for the shots to look richer and more vibrant effectively reflects the glamor and glory of the movie’s temporal setting, but even more so the film’s excellence, high class, grandeur. Besides, Tarantino’s outstanding cinematic manifestations of his widely discussed foot fetish finally feel like a good fit here. They work amazingly well with the flower child barefoot lifestyle thriving in the cultural scene of the 1960’s America. But it is not just the hippies that walk barefoot in his movies. We need to peer through Margot Robbie’s toes before fixating on her face and simply make ourselves comfortable with watching scenes of Rick and Cliff beer nights with their feet foregrounding the action – another visual barrier that has easily found its way into the cinematic look that is already withdrawn from inviting the viewer into its exclusive world.

Whilst making sure it mirrors its author’s style, tastes, and convictions (which is not surprising considering the versatility of Tarantino’s talent and high degree of involvement with all stages of the film’s development), OUATIH is a self-reflexive piece of cinema that expresses appreciation of the beauty of filmmaking less so through behind-the-scenes of Rick Dalton’s fictional westerns than through employing traditional cinematic techniques in a very conscious, presentational manner. One example of this is the interaction between Cliff and the red-haired Squeaky on the porch of a decaying shack where the blind George is kept by the hippies. To add to the alarming atmosphere of the Spahn ranch, with Cliff left alone to the mercy of dozens of its inhabitants, Tarantino uses a Dutch angle to shoot the conversation between Cliff and George’s “captor.” To add to this unsettling situation, as suggested by Squeaky’s menacing tone and a slow build of an ominous soundtrack, Tarantino uses a foreboding camera tilt, traditionally associated with increased dramatic tension. Compare the angle of these shots, each separated by only one cut. The characters’ dialogue, exclusively captured in a shot-reverse shot technique, in broad daylight, is not entirely consistent with your classic chaotic rapid action or multiple realities scenes in which the Dutch angle is normally used. Yet, whilst very aware of itself, it does not feel out of place at all: a certain sense of intoxication is looming through Squeaky’s dilated pupils and demonic speech, and the overpowering chaos has been established since Cliff first stepped on the ranch. But through its very self-conscious presence, the Dutch angle serves a function other than just adding to the suspense of the situation. It stands out, and, thus, purposefully draws attention to itself as a cinematic technique that has just been used. It is the film’s wink to the viewers – look, this is a good place to use this device. The abundance of the perfectly color-coded shots and fascinating match cuts between scenes work in a similar way: they point at the inner aesthetic of filmmaking, and they can be easily noted and named by those of us familiar with film theory.

And yet, OUATIH left me and a lot of viewers feeling overpowered, incomplete even. If we leave the theater confused, the confusion turns into frustration. Nobody likes feeling less knowledgeable, less cool, or less, than others. Am I disappointed because my film major friends were able to spot more Hollywood history references than I could? Or because it was obvious to my American friends that the hippies led by Tex were the Mansons? There were viewers, on the other hand, who left the cinema flattered by the film they just watched, loving it not because it is what the cinephile community tells them to do, but because they truly enjoyed this nostalgic tale of the Hollywood’s glorious past that just happened to be part of Sharon Tate’s tragic story. Maybe the movie was only made for some of us to enjoy and it is extremely aware of it. I should not be disappointed because I felt inferior to other people in the audience, but because OUATIH was just really good at setting strict boundaries between itself and me. From the first minutes, it pulls us in with its beauty and classiness, this magnetizing look and spirit of Hollywood. It brings the illusion to life but makes sure early on that only the selected few will get a closer look into it. Do not get attached too easily.

Now, two years older and a film student in the United States, I might have transcended the average audience member status, but after each new viewing, I still felt like the film was hiding from me. I might be turning into a more informed viewer, but one thing will be left unchanged: I care about impressing OUATIH more than it cares about impressing me. I remember wanting to be that person who can understand all of this film’s brilliance, and be “enough” of an audience member to appreciate and admire it. And that is where the greatness of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood lies: by making us crave its attention so badly, it pushed me and many others to inquire, learn, and grow – as critics, fans, and, most importantly, viewers.

Works Cited

Brown, Lane. “In Conversation With Quentin Tarantino.” Vulture, 23 Aug. 2015, https://www.vulture.com/2015/08/quentin-tarantino-lane-brown-in-conversation.html.

Copeland, Dave. Hollywood’s Violent Visionary: How Controversy and Critical Acclaim Fueled Quentin Tarantino. https://www.workandmoney.com/s/quentin-tarantino-bio-b76618ab297447f5. Accessed 17 Dec. 2021.

Crow, David. “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood Easter Eggs and Reference Guide.” Den of Geek, 14 Dec. 2019, https://www.denofgeek.com/culture/once-upon-a-time-in-hollywood-easter-eggs-references/.

Duncan, Russell. “The Summer of Love and Protest: Transatlantic Counterculture in the 1960s.” The Transatlantic Sixties: Europe and the United States in the Counterculture Decade, edited by Grzegorz Kosc et al., Transcript Verlag, 2013, pp. 144–73.

Elsaesser, Thomas, et al., editors. The Last Great American Picture Show: New Hollywood Cinema in the 1970s. Amsterdam University Press, 2004.

Farber, David. “Self-Invention in the Realm of Production: Craft, Beauty, and Community in the American Counterculture, 1964–1978.” Pacific Historical Review, vol. 85, no. 3, University of California Press, 2016, pp. 408–42.

Gerald, Michael C. “Drugs and Alcohol Go to Hollywood.” Pharmacy in History, vol. 48, no. 3, American Institute of the History of Pharmacy, 2006, pp. 116–38.

Guinn, Jon. “The Brilliant Symbolism of Spahn’s Movie Ranch in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.” Truth of Media. https://medium.com/truthofmedia/the-brilliant-symbolism-of-once-upon-a-time-in-hollywoods-manson-family-and-spahn-s-movie-ranch-f1dae3e00931. Accessed 21 Oct. 2021.

Hooton, Christopher. “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood Isn’t a Love Letter, It’s an Obituary.” Little White Lies, https://lwlies.com/articles/once-upon-a-time-in-hollywood-quentin-tarantino-love-letter-obituary/. Accessed 17 Dec. 2021.

Horwath, Alexander. “The Impure Cinema: New Hollywood 1967-1976.” The Last Great American Picture Show: New Hollywood Cinema in the 1970s, edited by Thomas Elsaesser et al., Amsterdam University Press, 2004, pp. 9–18.

McClintock, Pamela. “Box Office Milestone: ‘Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’ Crosses $200M Globally.” The Hollywood Reporter, 24 Aug. 2019, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/once-a-time-hollywood-box-office-crosses-200m-globally-1234303/.

McGowan, Elisabeth. “Once Upon A Time In Hollywood: 10 Easter Eggs & References In Tarantino’s Movie.” ScreenRant, 24 Feb. 2021, https://screenrant.com/once-upon-a-time-in-hollywood-quentin-tarantino-best-easter-eggs-references/.

McGrath, Charles. “Quentin’s World.” The New York Times, 19 Dec. 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/23/movies/how-quentin-tarantino-concocted-a-genre-of-his-own.html.“

‘Once Upon a Time’ Divides Audiences on Its Historical Context.” The Daily Dot, 30 July 2019, https://www.dailydot.com/upstream/once-upon-a-time-manson-killings-context/.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood References Guide – The Quentin Tarantino Archives. https://wiki.tarantino.info/index.php/Once_Upon_a_Time_in_Hollywood_References_guide. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

Tallerico, Brian. “‘Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’ Easter Eggs & References.” Vulture, https://www.vulture.com/article/once-upon-a-time-in-hollywood-influences-references.html. Accessed 21 Oct. 2021.

Vanity Fair. “Leonardo DiCaprio & Quentin Tarantino Break Down Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’s Main Character.” 2019. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cF76gm9PdOs.