Rachel Roseman is an AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer (2017- 2018) at the Center for Community Engagement at Middlebury College. Literatures & Cultures Librarian Katrina Spencer poses some questions and has Rachel share on the Privilege & Poverty Academic Cluster and balancing core duties with creative projects.

Rachel, we first met over email when you shared a thematic Spotify playlist centered on economic inequality. Tell me how this idea came about.

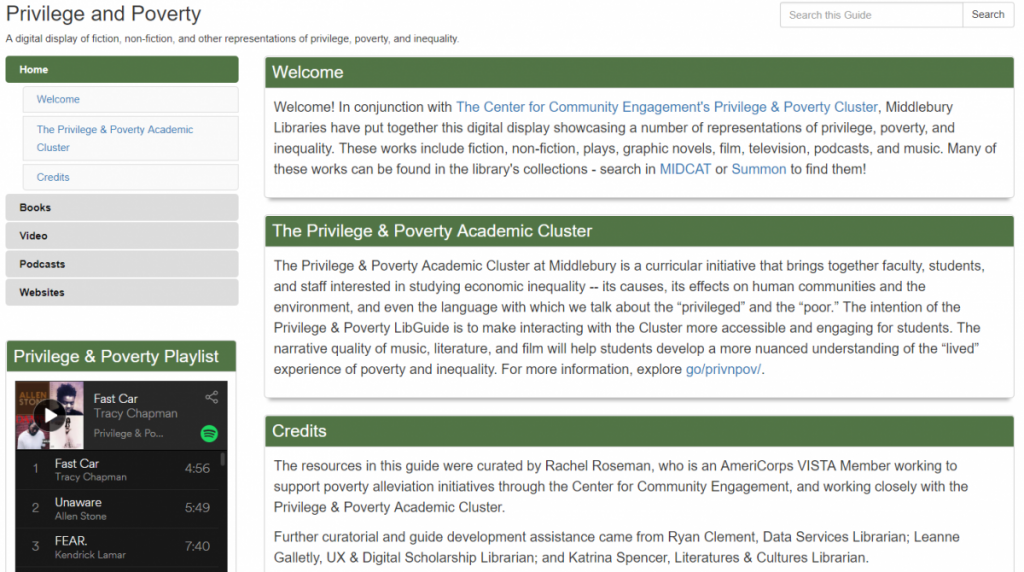

Let me begin by stating what the Privilege & Poverty Academic Cluster (P&P) is–

The Privilege & Poverty Academic Cluster at Middlebury is a curricular initiative that brings together faculty, students, and staff interested in studying economic inequality — its causes, its effects on human communities and the environment, and even the language with which we talk about the “privileged” and the “poor.”

The Cluster is not a formal major or minor, but rather a program with coherence, relevance, and intellectual depth that complements any other major course of study. Participating students also have opportunities to combine theory and practice, insofar as their work with collaborating organizations, which directly address poverty-related issues in the community. Taking advantage of an abundance of resources and expertise, at the College and in our community relationships, we are cultivating skills, knowledge, capacities, and moral sensitivities essential to the address of this social problem. For more information, explore go.middlebury.edu/privnpov.

… Now that I have concluded the elevator pitch, let us dive in.

There are two primary ways in which students can interact with the Cluster–the flagship course, Privilege and Poverty: The Ethics of Economic Inequality, and the summer internship programs, one national and one local. The Center for Community Engagement supplements these opportunities with additional programming throughout the academic year, such as a monthly discussion series, where we unpack poverty-related topics over lunch. Past topics have included hurricane gentrification, access to healthcare, and equity in education. I also facilitated the P&P Book Club, a 2018 Winter Term Workshop for which 26 students registered. Throughout the workshop, we read Linda Tirado’s Hand to Mouth: Living in Bootstrap America and explored different multimedia depictions of poverty, such as the pilot episode of Shameless and PBS Frontline documentary: Two American Families. You can consult the workshop materials at go.middlebury.edu/povertybookclub.

As we discussed Hand to Mouth, students commented about how Tirado brings to life her experience of poverty in a way that isn’t necessarily taught in courses. I began to consider how we could bridge the gap between the theoretical understanding of economic inequality with the “lived” experience of poverty. How could the Cluster help students develop a more nuanced understanding of the day-to-day experience of poverty? As Tirado writes in Hand to Mouth, “Poverty, or poor, or working class–whatever level of not enough you’re at–you feel it a million tiny ways. Sometimes it’s the condescension; sometimes it’s that you’re itchy” (79). Thus, the idea for a Privilege & Poverty playlist was born, which is featured here.

A musical playlist seemed like the natural medium to explore issues of economic inequality, since there’s an existing model of reciprocity between music and social justice—the Civil Rights Movement and Vietnam War are the first images that come to mind. Ray Pratt observes in Rhythm and Resistance, “No music alone can organize one’s ability to invest affectively in the world, [but] one can note powerful contributions of music to temporary emotional states” (39). This emotional connection between artist and listener is exactly what I attempted to facilitate with the Privilege & Poverty playlist.

Data Services Librarian Ryan Clement helped me to navigate how to how to best showcase the playlist, which is how I began the process of developing the Privilege & Poverty Libguide. Modeling the Privilege & Poverty Libguide after the Black History Month lib guide, I started searching MIDCAT for resources in multiple formats. I wanted to curate a robust list of resources and found works of fiction, non-fiction, plays, graphic novels, film, television, podcasts, and other web content that would be popular with students.

Collecting information on a theme and presenting it in an accessible way is very much a skill practiced by librarians. Did you realize that when you started?

This interview is really the first time I have contextualized my project beyond the realm of the Privilege & Poverty Academic Cluster. The entire process was very organic—I noticed a point for improvement and sought to address it creatively. Did I realize at the time that I was strategically planning and exercising curriculum development skills? Nope! However, I’m at the point in my career where I should begin to address how to best balance the creative process with the strategic planning process.

Although I’ve never considered pursuing library science as a profession, I did work at Albright College’s Gingrich Library throughout my undergrad career. One of my favorite aspects of that job was curating library displays. One of them featured “banned” books, so other staff and I wrapped crime scene tape around the bookshelf.

Libraries actually play an important Privilege & Poverty role in society, because they are — or should be — as Amanda Killian tweeted, one of the few safe havens for individuals to exist without the expectation of spending money. Libraries should be open institutions where all are welcome. They can also provide educational materials and technical equipment, such as reference books, computers, and printers, to which individuals may otherwise only have limited access. Of course, we cannot discuss equity and inequality without recognizing that certain communities, primarily those of color, do not receive adequate funding — if they receive funding at all — for public libraries. Class, race, and gender are all interlocking systems, so in order to address one, you have to address them all.

In all transparency, I experienced poverty growing up in rural Pennsylvania, but my parents always budgeted for books. If that budget ran out, then we always visited the local library. If I, as a Fulbright grant recipient and AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer, have had any semblance of success, then it is because my family ensured access to books was a priority.

As an AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer, tell me how your work is different from and similar to other staff members’.

As an AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer, my service is both similar and different from the work of other staff members at the Center for Community Engagement. It’s similar in that I am just as committed to my projects, students, and institutional goals as any other employee. I, like my colleagues, strive continually to assess my privilege and implicit biases in order to view things through a lens of equity and inclusion, which I believe is necessary of any nonprofit work. It’s different in that I am not technically an employee of the college. I don’t receive an hourly pay or salary, but rather the Corporation for National and Community Service provides me with a meager living stipend which is calibrated around the federal poverty line for Addison County, Vermont. This means that while I liaise between the college and poverty-related organizations in the area, I also depend on their services. In many ways, I embody Privilege & Poverty by serving at such an elite and well-endowed institution and understanding the perspective of the College, while simultaneously understanding the perspective of the town and those experiencing poverty in Addison County.

My service term is one year, so I’ll be at the Center for Community Engagement until mid- to late August 2018. VISTA volunteers have assignment descriptions, which outline objectives and expectations. I like to think of my assignment description as the baseline of what I’m expected to accomplish and try to think of creative projects to supplement it, such as the Book Club, Libguide and more. In my opinion, VISTA volunteers are vital to their host sites because they provide a set of fresh eyes and the ability to shake things up. Along with Christina Grier, Services Director at WomenSafe, I’m currently in the process of coordinating a pre-service training for the Privilege & Poverty national and local interns focused on trauma-informed approaches to working with vulnerable populations.

How do you and the Center for Community Engagement interact with the libraries?

The Center for Community Engagement coordinates a few library displays throughout the year, but the possibilities are endless. I’d really like to see a Privilege & Poverty library display or one on migrant farm workers in Vermont. Open Door Clinic, a health care clinic for uninsured and underinsured individuals, actually spearheaded a comic book project that collected stories from migrant farm workers in Addison County and enlisted local artists to illustrate their stories. The title of the comic book series is, “El viaje más caro/The Mostly Costly Journey.” [Ed. note: Twelve titles in this series are available to read in the library’s Special Collections & Archives.] The project was a way to both give voice and authority to migrant workers in the area and educate the broader Addison County community about these issues.

I also wonder what it would look like to curate an interactive display that somehow assists students in checking their own privilege and offers suggestions on how to use their privilege to help uplift others with different/less privilege.

What do you anticipate following your service?

I enrolled as a VISTA volunteer because I was strongly considering pursuing public interest law. Because law school is such an awesome expense and commitment, I wanted to gain valuable, real-world experience with public-interest work as a way to dip my toes in the water, so to speak. Now that my service is over half-complete, I’m considering a second service term in a legal setting. Among other things. I intend to sit for the LSAT (Law School Admission Test) this September.

Rachel, thank you so much for your time!

Thank you for reaching out to me and featuring my project in your newsletter!