![]() We know very little about Timothy O’Sullivan’s beginnings as a photographer, or, indeed, his life at all. He began his career working in the portrait studio of Mathew Brady, and then was one of Brady’s team of photographic “operators” on the battlefields of the Civil War. Although his work is greatly admired today as, in the words of photography historian Keith Davis, “the paradigmatic expression of American landscape or expeditionary photography in that era,” in his own lifetime O’Sullivan’s role was that of a workman who fulfilled his assignments of documenting utilitarian subjects.[footnote]Keith F. Davis, “Representing the West: From Lewis and Clark to the Great Surveys of 1867-79,” in Keith F. Davis and Jane L. Aspinwall eds., Timothy O’Sullivan: The King Survey Photographs (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), p. 14.[/footnote] Nevertheless, his mastery of his craft and his personal vision elevated his work above that of his contemporaries.

We know very little about Timothy O’Sullivan’s beginnings as a photographer, or, indeed, his life at all. He began his career working in the portrait studio of Mathew Brady, and then was one of Brady’s team of photographic “operators” on the battlefields of the Civil War. Although his work is greatly admired today as, in the words of photography historian Keith Davis, “the paradigmatic expression of American landscape or expeditionary photography in that era,” in his own lifetime O’Sullivan’s role was that of a workman who fulfilled his assignments of documenting utilitarian subjects.[footnote]Keith F. Davis, “Representing the West: From Lewis and Clark to the Great Surveys of 1867-79,” in Keith F. Davis and Jane L. Aspinwall eds., Timothy O’Sullivan: The King Survey Photographs (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), p. 14.[/footnote] Nevertheless, his mastery of his craft and his personal vision elevated his work above that of his contemporaries.

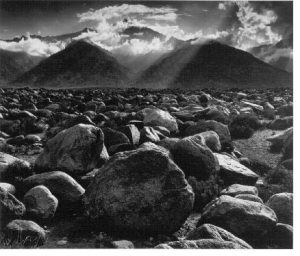

In 1867, O’Sullivan was selected for the Fortieth Parallel Survey led by Clarence King. Over the course of three years, O’Sullivan photographed landscapes and geological formations, factories and towns, mines, group portraits of the survey team, and strange views that Davis has called “sophisticated meditations on his own role as witness and recorder.”[footnote]Keith F. Davis, “Representing the West: From Lewis and Clark to the Great Surveys of 1867-79,” in Keith F. Davis and Jane L. Aspinwall eds., Timothy O’Sullivan: The King Survey Photographs (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), p. 73[/footnote] The results of the survey were published in seven text volumes and two atlases, with lithographs made after O’Sullivan’s photographs illustrating some of the texts; however, few photographic prints were made. A small number of photographs on official survey mounts was issued by the survey, and in 1876 a set of 180 prints was produced in an edition of six in conjunction with the Philadelphia Centennial exhibition. Miscellaneous prints and stereographs were made through the 1880s, but there is no evidence that these were available for purchase.

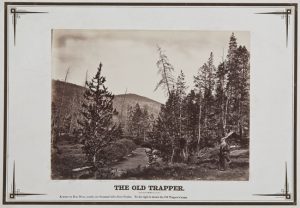

O’Sullivan’s The Old Trapper (also titled Upper Bear River, Utah) was made in 1869 as part of the King Survey. Unlike his views of mining towns and railroads, which look forward to expanding settlement in the region, The Old Trapper casts a nostalgic look back to the early days of the frontier, when fur trapping led intrepid mountain men to the West. After the fur trade peaked in the early 1830s, many former trappers became trail guides for settlers.

This photograph was probably staged, perhaps even as a joke. One copy has a pencil notation on the mount, “Munger as Squaw?”[footnote]Keith F. Davis, “Representing the West: From Lewis and Clark to the Great Surveys of 1867-79,” in Keith F. Davis and Jane L. Aspinwall eds.,Timothy O’Sullivan: The King Survey Photographs (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), catalogue raisonné no. 145.[/footnote] Painter Gilbert Munger joined the King survey as a guest artist in 1869, and he may have posed as the nearly illegible “trapper” figure on the right. Printed on the mount of the Middlebury College Museum’s copy of the photograph is the notation “to the right can be seen the Old Trapper’s home,” although this home is simply a rough tarp mounted on poles similar to one seen in other photographs of the survey team. As the frontier was quickly diminishing and the wilderness giving way to farms and towns, perhaps the old trapper photograph satirized the olden days that preceded the current era of progress.

I

I Eliot Porter took up color photography at a time when it was widely considered “too literal,” and thus unsuitable for artistic images. His book, In Wildness is the Preservation of the World, marked a turning point in the acceptance of fine art color photography. The book was the first of many color books that the Sierra Club would publish by a variety of artists, and the first of twenty-five monographs of color photos Porter would produce.

Eliot Porter took up color photography at a time when it was widely considered “too literal,” and thus unsuitable for artistic images. His book, In Wildness is the Preservation of the World, marked a turning point in the acceptance of fine art color photography. The book was the first of many color books that the Sierra Club would publish by a variety of artists, and the first of twenty-five monographs of color photos Porter would produce.