![]() Just a decade before Marilyn Bridges first began photographing from the air, artist Robert Smithson published an essay titled “Aerial Art,” in which he wrote: “The old landscape of naturalism and realism is being replaced by the new landscape of abstraction and artifice.” As Smithson argued, the aerial view bypassed traditional pastoral views of the agricultural landscape, since from the sky “the landscape begins to look more like a three-dimensional map rather than a rustic garden.”[footnote]Joshua Schuster, “Between Manufacturing and Landscapes: Edward Burtynsky and the Photography of Ecology,” Photography & Culture 6(July 2013), p. 207.[/footnote]

Just a decade before Marilyn Bridges first began photographing from the air, artist Robert Smithson published an essay titled “Aerial Art,” in which he wrote: “The old landscape of naturalism and realism is being replaced by the new landscape of abstraction and artifice.” As Smithson argued, the aerial view bypassed traditional pastoral views of the agricultural landscape, since from the sky “the landscape begins to look more like a three-dimensional map rather than a rustic garden.”[footnote]Joshua Schuster, “Between Manufacturing and Landscapes: Edward Burtynsky and the Photography of Ecology,” Photography & Culture 6(July 2013), p. 207.[/footnote]

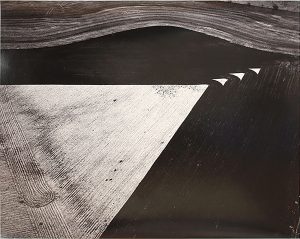

This is certainly the case in her photograph, Geometries, Lone Wolf, Oklahoma, where farmland is translated into pattern, and details succumb to a study in shape and contrast. Still, Bridges sees her subjects as more than formal designs. As she wrote in an essay published in 1997, “I hope to alter the old steadfast view that the land is simply something we live on. I want the viewers to feel they are looking down over the edge of a precipice, and that the discomfort and disorientation they feel is part of the discovery.”[footnote]Marilyn Bridges, “Afterword,” in This Land is Your Land: Photographs by Marilyn Bridges (New York: Aperture, 1997), p. 106.[/footnote]

Bridges photographs what she calls the “calligraphy” of humanity’s attitudes toward the earth, as visible from the sky. Lacking horizons and ground-view spatial relationships, and oscillating between geometric abstractions and topographical documents, her compositions urge us to consider the implications of our relationship with the surface of the earth.