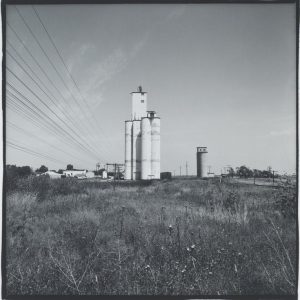

In 1971, Frank Gohlke began photographing a huge depot of grain elevators seen from his home in Minneapolis, transforming the buildings into, in the words of John Rohrbach, “dreamscapes of gigantism and hidden power.”[footnote]John Rohrbach, “Who’s In Control Here?” in Accommodating Nature: The Photographs of Frank Gohlke (Chicago: Center for American Places in associations with the Amon Carter Museum, 2007), 129.[/footnote] This led to a sustained project of photographing grain elevators throughout the Midwest. The resulting photographs, including Grain Elevator, Hutchinson, Kansas, show agricultural landscapes punctuated by massive buildings that rise far into the sky from the flat fields surrounding them.

In 1971, Frank Gohlke began photographing a huge depot of grain elevators seen from his home in Minneapolis, transforming the buildings into, in the words of John Rohrbach, “dreamscapes of gigantism and hidden power.”[footnote]John Rohrbach, “Who’s In Control Here?” in Accommodating Nature: The Photographs of Frank Gohlke (Chicago: Center for American Places in associations with the Amon Carter Museum, 2007), 129.[/footnote] This led to a sustained project of photographing grain elevators throughout the Midwest. The resulting photographs, including Grain Elevator, Hutchinson, Kansas, show agricultural landscapes punctuated by massive buildings that rise far into the sky from the flat fields surrounding them.

Taking part in the important exhibition, “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape” in 1975 at the George Eastman House, Gohlke joined eight other photographers in producing dead-pan records of landscapes that acknowledged the place of human intervention in nature. Working counter to the idealized views of Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter, New Topographics photographers looked to the vernacular landscape and its architecture as a key to understanding contemporary culture.

Gohlke’s photographs stand out for their emphasis on the agricultural landscape and the symbols inherent in it. Rebecca Solnit writes of Gohlke’s grain elevator photographs, “grain elevators challenge the horizontality of the landscape, becoming watchtowers or church spires; but it only takes a moment to realize that those structures were made to hold grain and that they, stark against the sky, speak of the great expanses of level, arable land and the people who toil there. The grain that fills a grain elevator is, after all, the horizontal piled high.”[footnote]Rebecca Solnit, “Comfort and Debris,” in Accommodating Nature: The Photographs of Frank Gohlke (Chicago: Center for American Places in associations with the Amon Carter Museum, 2007), 156.[/footnote]