Symposium Report: Some Preliminary Reflections on Reconceptualizing Cultural Histories of the Atlantic World, Digitally and Interculturally

After our veritable feast of Atlantic World history scholarship, as well as our productive opening conversation and many informal discussions, where do we stand? Here are some initial (“sketchy,” as it were) reflections.

- How do we contribute new frameworks and conceptual approaches to Atlantic World, trans-oceanic, transnational, and global history?

Flows, Circulations, Hubs, Displacements, Reconfigurations, and…Portals?

With both the Transatlantic Cultures platform and the Atlantic World Forum, we return repeatedly to the question of conceptualizing the Atlantic World as a place of flows and circulations. To be sure, we do not wish to erase the power wielded by centers over peripheries, the continued legacies of various imperialisms, but we also want to become more aware of how those dynamics played out in less predictable ways in the empirical record of the Atlantic World. To do so, cultural history, broadly conceived, is productive because cultural forms and interactions offer spaces and practices of potent if decentralized processes of making—and especially of remaking.

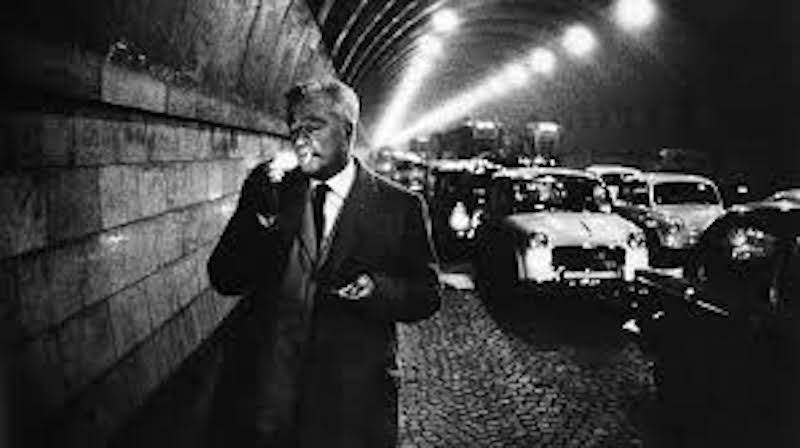

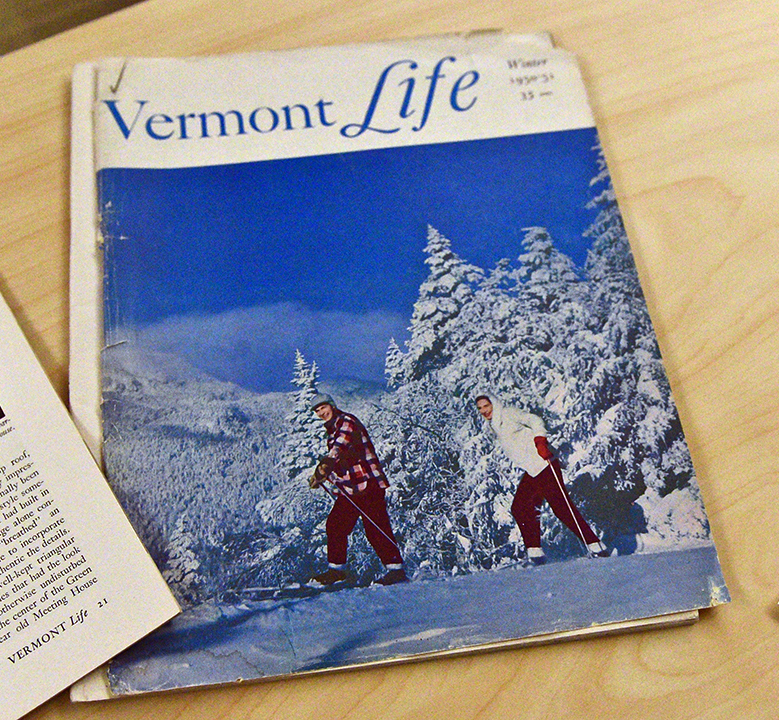

Indeed, building on a comment by Anaïs Flétchet, I too noticed that this remaking often appeared when one of our presenters tracked the movement of Atlantic World participants through various displacements, movements, and relocations. It is often distance, whether forced or voluntary or some combination of the two, which helps to create place-based cultural, institutional, economic, and political formations. We see this when Gilberto Gil (as Anaïs studies) or Alan Lomax (as I study) resettled in what Marcos names as a “hub” (rather than a center) of the Atlantic World: London. We hear it in listening to the stories of how the Old Klezmorim become new—and then, in a way, old again—in Jean-Sébastien Noël‘s research. It appears when we glimpse the people of St. Kitts transferring some, but not all, aspects of the West African significance of one plant (Dracaena) onto another one (Cordyline) that seems similar in look, but in fact arrived in St. Kitts from Tahiti thanks to the British Empire, as Michael Sheridan studies. It becomes manifest too, even in disguised costumes, in the appropriations of Shakespeare in the Masque rituals of Mardi Gras on the island of Carriacou, as Dan Brayton studies. We notice the importance of displacement and relocation in the move to Liberia by Middlebury graduate and Rutland, Vermont, native Martin Freeman, as Will Hart describes it. We see it, as Michele Greet teaches us, in the ways in which the very definition of modernist Latin American visual art is shaped by the experiences of Latin American artists and their networks of dealers, salons, socializing, and more across the Atlantic in Paris (another hub to be sure). It emerges again, as Gabriela Pellegrino shows, in the commercial publishing practices of W.M. Martin and his Book of Knowledge as assembled and reassembled in various permutations around the Pan-American world. We grasp the significance of institutional re-situation (almost translation) in the use of Pan-American cultural exchange to try to shape US public opinion, as Richard Cándida Smith investigates. The importance of displacement, reconfiguration, and distance appears again in the Methodist photographs taken by missionaries and assembled, in frustratingly disorganized form, into albums back at the main offices of the Methodist church, as Didier Aubert shows us. And it is present, as Daniel Silva is analyzing, in the story of fitness culture as a way of inculcating, at an almost invisible yet also profoundly corporeal level, a national, normative sense of what it means to be “Brazilian.” Here it is partly the distance between the ideologies and the bodies onto and into which these ideologies gets placed (where they are quite literally made muscular) that allows them to function.

These stories are all marked not only by flows and circulations, but also by key displacements that, like portals, remake the peoples, cultures, economics, social forms, and political formations of the Atlantic World by causing them to pass through transformations. In other words, one way to get a sense of place in this history is precisely through movement; one way to look toward specific histories is by, in an odd way, looking askance at them. The periphery, as we have long known, turns out to be core to the story. Place emerges from displacement. Culture provides a way to glimpse how in circulations and flows larger struggles, contestations, negotiations, reconfigurations have occurred. Therefore, perhaps like flows, circulations, and hubs, portals might become another productive keyword for this project.

Flows, Circulations, Hubs, Displacements, Reconfigurations, Portals, and…Currents?: Getting Decentralized and Connected at the Same Time

Additionally, one tension I believe we noticed (articulated by Gabriela) in these projects is that we must balance our interest in multiplicity without creating complete fragmentation. How might we use the layered, multidimensional qualities of the digital platforms to present the overlaps and the gaps among the many frameworks for Atlantic World study (transatlantic, circum-Atlantic, Black Atlantic, hemispheric, Pan-American, colonial and postcolonial, diasporic, etc.)? At the same time, how do we create coherent, connected history? Perhaps the metaphor of currents, taken from the movements of water in the Atlantic itself (Gulf Streams, etc.) might help us better consider and historicize two opposing thematics: sometimes there are what Lara Putnam, borrowing from Kamau Braithwaite, calls the “submarine unities of Atlantic history” that rest beneath the “above-water fragments”; at the same time, we also seek to complicate the assertions of above-world unities that hide the great diversity of stories within Atlantic World circulations and flows. If we can trace the ironies of these seeming contradictions effectively perhaps that is a path to better historicization and crystallization of this very large, dare I say oceanic, story.

From Structure and Agency, Domination and Resistance to Other Frameworks?

A final observation: as Richard Cándida Smith noted that he learned in his study of Pan-American cultural exchange, and as Didier Aubert also suggested in his work on the photography by Methodist missionaries in places such as Chile, and indeed lurking in much of our research is a different framework for thinking about power and culture. Rather than privilege ideology alone as a shaping force, we noticed in cultural forms the complicated interactions between institutional forces in the economic and civil spheres (publishing, academic and professional associations, religious organizations and practices, art world dealers and salons, public holiday traditions, etc.) and ideological urges (nation-state formation, capitalism, socialism) and aesthetic gestures (music, visual art, vernacular expression). This is not completely different from existing frameworks we use as historians, such as structure and agency or domination and resistance (or hegemony and counter-hegemony in the Gramscian sense), but it does point to a slightly different way of considering (borrowing again from Richard) the pragmatics of Atlantic World cultural histories, the ways in which culture and power, continuity and disruption, emerge from concrete and specific situations rather than the actual lived experience of the Atlantic World arising from abstract forces. With everything from Paul Gilroy’s Black Atlantic “practical philosophy” to the “transmodernity” that Walter Mignolo examines to other seemingly abstract dimensions of Atlantic World history, these research projects on the Atlantic World, brought into a shared digital platform and space, have the potential to reveal both the very particular instantiations of larger forces and show how the larger forces only arise from the particular empirical examples. In short, here is a way to, as Bill Hart put it, responding to the work of Lara Putnam, create better duets between microhistories and epic histories—as he put it, to grasp the interactions between “the Small and the Mighty.”

Overview of Project

Atlantic World Forum Kickoff Symposium

Creating Digital Scholarly Dialogues About Atlantic World Cultural Histories

Rohatyn Center for Global Affairs, Robert A. Jones ’59 House/Davis Library 105B

Middlebury College

Tuesday-Wednesday, October 16-17, 2018

A two-day symposium introduces the DLA project Atlantic World Forum: Reimagining the Online Scholarly Roundtable, Reshaping the Global Digital Humanities, Reframing Circum-Atlantic Cultural Histories at Middlebury.

Partnering with a larger French-Brazilian-led endeavor, Transatlantic Cultures, AWF harnesses the interactive and multimedia dimensions of the digital domain to foster international dialogues on circum-Atlantic cultural history. Each Atlantic World Forum roundtable assembles a group of five to seven scholars from various countries and focuses on a particular theme. The participants meet and exchange ideas by digital means as each one works on a multimedia essay. Projects might also include their exchanges leading to the multimedia essays and after their publication. Other digital work will emerge as well: maps, timelines, databases of primary source material, and invited commentary by additional experts. We seek to distribute the forum in digital modes accessible in various places, whether it be by the web in the US and Europe or by mobile phone in West African countries or even paquetes in Cuba. One to two distinct forums are planned for each year.

Through a proposed seminar taught each semester at Middlebury by DLA Acting Director and historian Michael Kramer, students combine historical pedagogy in Atlantic World history, from its origins in Anglo-American colonial studies to later work on the Black Atlantic to other approaches, with hands-on digital and experiential learning. They work with the participating scholars to conduct research, develop digital and multimedia components for essays, hone editing and project management skills, and innovate new modes of digital humanities collaboration, narrative, and scholarly communication. Potentially, students at other institutions can join the project as well.

Faculty at Middlebury are able to contribute to roundtables, advance their own research when applicable, and incorporate the project into teaching when appropriate. Faculty and students at the Translation and Interpretation program and Middlebury Institute Globe Multilingual Language Services will work with the project on translation of the AWF into multiple languages. Faculty and students at Middlebury’s Schools Abroad and Monterey courses in Intercultural Competency, Intercultural Rhetoric, and Intercultural Digital Storytelling can participate as well in future meetings and exchanges so that AWF contributes to the substantive strengthening of Middlebury’s global networks of scholarship.

Funding for the Kickoff Symposium was generously provided at Middlebury by the DLA, Rohatyn Center for Global Affairs, DLINQ, Academic Enrichment Fund, and Pedagogy Enrichment Fund.