A Vicious Cycle Between Poverty & Disability:

We see from the previous maps here that there is a clear correlation between poverty and disability. But not only does having a disability lead to an increased risk of poverty, there is also evidence of a vicious cycle between the two. In this way, disability can be seen as both a cause and consequence of poverty. It is a cause because disability can affect factors complicating employment outcomes, such as skill and educational attainment, number of hours worked, earnings, and discrimination. At the same time, disability is also a consequence of poverty as low-income levels limit access to adequate health care and resources.

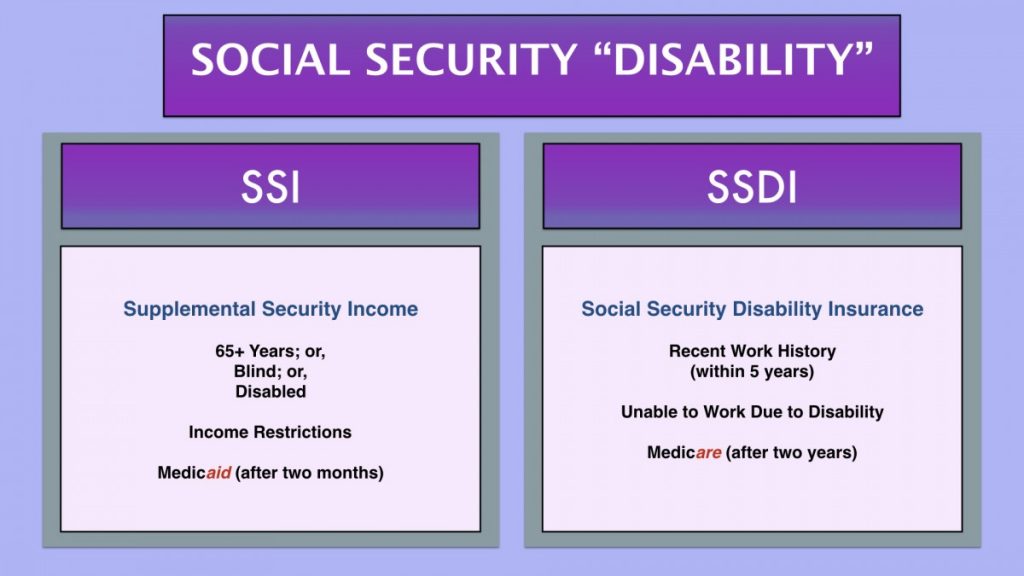

While SSDI & SSI are designed to help those stuck in the cycle of poverty and disability and have been proven to be a complete safety net for so many disabled individuals, some conservatives argue that these programs are just exacerbating the problem of poverty, allowing people to stay comfortable within the system rather than aiding them to escape it. If the only hope for a family is to claim disability benefits, it may call for desperate measures — such as pushing family members towards applying for benefits.

According to a NYT Article, Profiting from A Child’s Illiteracy,“This is what poverty sometimes looks like in America: Parents here in Appalachian hill country pulling their children out of literacy classes. Moms and dads fear that if kids learn to read, they are less likely to qualify for a monthly check for having an intellectual disability.” While it may be the minority of cases, families may have to take drastic and heartbreaking measures to keep their child’s disability checks [children can receive them up until age 18]. Richard V. Burkhauser, a Cornell University economist, notes that, “If you do better in school, you threaten the income of the parents. It’s a terrible incentive.” Education is a prime motivator of socioeconomic outcomes, and we should be encouraging it for children. The main issue is that SSDI and SSI offer barely livable income amounts to parents, and thus often rely on their children to also receive benefits from SSI. There should be an emphasis not only on livable incomes, but on creating opportunities for children in these families.

There has been a lot of criticism on this article, written by author Nicholas Kristof. In another recent response, critics point out that “98.6 percent of non-institutionalized SSI children ages 6-12, and 90.7 percent of those ages 13-17, are enrolled in school, and three-fourths receive (or have received) special education.” This is not to say that the examples Kristof discusses are irrelevant and never happen, but that his story cannot explain the majority of cases. They conclude by pointing out that “It is essential to fund SSA’s administrative costs properly so the agency can keep up with disability claims, review disability cases regularly, end benefits for those who no longer need them, and root out the isolated cases of fraud.” The examples of fraud we see, in articles like these ones, are such a small fraction of all cases receiving benefits.