As Bill Mckibben remarked in his book, Wandering Home: A Long Walk Across America’s Most Hopeful Landscape, “If we’re going to talk about the wilderness, we have to face the truth that it’s a little hard to separate out the natural and the artificial” (McKibben 68). At Middlebury, wilderness is all around us. The lush Green Mountains to our East beam with a vibrant shade of green that I would never see in Los Angeles, where I’m from. However, how much of the Green Mountains, and other protected wilderness in this country for that matter, are truly “wild” anymore? Have humans permanently blurred the line between the natural and artificial? Despite their lawful protection, humans have altered wilderness to an extent that natural systems face severe disruption, both directly and indirectly, losing their vibrancy, biodiversity, and perhaps their “wilderness”.

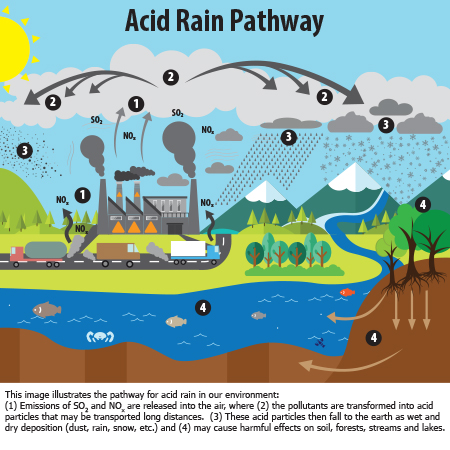

Drought, hurricanes, severe flooding, and countless other natural disasters are becoming more common as a direct result of human activity. For example, according to the Adirondack Council founded in 1975, the Adirondacks has experienced some of the worst recent damage from acid rain, which not only parches its forests and suffocates fish populations, but has adverse effects on the people who call this lush area of New York home (Figure 1). The Adirondacks has seen fewer cases of acid rain in the past year, yet one must wonder how much its ecosystem was permanently scarred as a result. How much of the Adirondacks’ “wilderness” did we lose over the past few years with acid rain? Considering other factors such as infrastructure, motor vehicles, and private estates, how “wild” are the Adirondacks anymore?

It is challenging to settle on whether our state and national parks are still “wild” without understanding the definition of “wilderness.” However, according to the WILD Foundation, the term “wilderness” is “subject to interpretation” as multiple frames of context are required and can either be used relatively loosely or precisely. Therefore, depending on whether you are reading state law or at the dinner table, the term “wilderness” can be used and interpreted in many ways. The WILD Foundation defines wilderness as: “The most intact, undisturbed wild natural areas left on our planet – those last truly wild places that humans do not control and have not developed with roads, pipelines or other industrial infrastructure.”

When reading this definition, however, it is difficult to think of many places in this country, and even around the world, that aren’t controlled or developed by humans. We essentially have control over our planet, whether it is physically altering its topography or provoking the upticks in natural disasters and changes to the climate. Whether or not protected lands on this planet are truly “wild” is up to interpretation, yet in order to continue preserving these vital ecosystems, we must consider making the term “wilderness” more applicable. Perhaps if we define this term more clearly, the way in which we connect with our one and only planet could change for the better.

Works Cited

Adirondack Council. “Acid Rain.” Adirondack Council, 2021, www.adirondackcouncil.org/page/acid-rain-86.html.

Foley, Martha, and Curt Stager. “Adirondack Lakes Recover from Acid Rain, but with an Altered Ecosystem.” NCPR, 10 Sept. 2020, www.northcountrypublicradio.org/news/story/35553/20200910/adirondack-lakes-recover-from-acid-rain-but-with-an-altered-ecosystem.

McKibben, Bill. Wandering Home: A Long Walk Across America’s Most Hopeful Landscape. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2014.

WILD Foundation. “Defining Wilderness – Wild Foundation.” WILD Foundation – Defending Earth’s Life-Saving Wilderness, 15 July 2020, wild.org/defining-wilderness/.

This was one of the question that got me thinking while reading “wandering home” and it got me thinking again after reading your post. I also think that probably almost nowhere is truly “wild” anymore just because that’s how much we have explored and put our hands on the “wild”.

Your thought on making the term “wilderness” more applicable is very interesting too, although I would argue that actually changing the definition/ creating an entirely new term to define what we have left, might be better considering how far humans have come.

This is a really interesting question. I would argue that nothing is truly wild to humans anymore, at least not nearly to the extent that our early ancestors faced. Something about, for example, the preparation and equipment necessary when going on a hike makes even the deepest portions of the woods feel less wild. Because although these areas may be undisturbed by industrialization, we humans like to personally surround ourselves by technology for our own safety and comfort.