THE DRUG WAR IN AMERICA

I. INTRODUCTION

The Wire unabashedly delves into many aspects of urban America and inner-city collapse, exposing the institutional flaws and social ills of American city life. One of the most glaring issues that it attacks head on is the war on drugs. The Wire captures and explores one of the greatest pitfalls of American political policy and law enforcement, as well as the thriving underground economy that stems from drug trade and use. The war on drugs acts as a catalyst for the plot of Season 1 and continues as a driving thematic force for the rest of the series. The Wire not only portrays the operational aspects of drug trade and police action against it, but it also explores the war on drugs as an anthropological phenomenon. In an editorial to a March 2008 Time Magazine issue, a collection of writers for The Wire, including co-creators Ed Burns and David Simon, discuss the social marginalization that has occurred as a result of the drug war:

What the drugs themselves have not destroyed, the warfare against them has. And what once began, perhaps, as a battle against dangerous substances long ago transformed itself into a venal war on our underclass. Since declaring war on drugs nearly 40 years ago, we’ve been demonizing our most desperate citizens, isolating and incarcerating them and otherwise denying them a role in the American collective. All to no purpose. The prison population doubles and doubles again; the drugs remain. [1]

The negative effects of the drug war are equally far-reaching and deep. The Wire attempts to capture the effects of this campaign and through both, explicit and implicit measures, condemn its existence. In the following context, we attempt to describe the ins and outs of the war on drugs and all the while shed light on how it all relates to The Wire.

II. THE HISTORY OF THE WAR ON DRUGS

The “War on Drugs,” as labeled as such, has existed for nearly four decades in the United States. However, this country’s battle with the prohibition of mind-altering substances unofficially began long before Richard Nixon’s stint in the White House. One could argue that the original “War on Drugs” was conceived in 1920 with the enactment of national Prohibition. Prohibition, much like the modern “War on Drugs,” began as a social experiment, with the intention of rectifying social and cultural ills, perceived to be created by the consumption and abuse of alcohol. It was argued that the prohibition of alcohol would decrease crime by eliminating drunkards, reduce the tax burden brought on by the incarceration of these criminals, terminate poorhouses as the lower-classes would become sober, and improve public hygiene in the cities, subsequently leading to lower death rates. [2]

www.newspeakdictionary.com/ct-prohibition.html

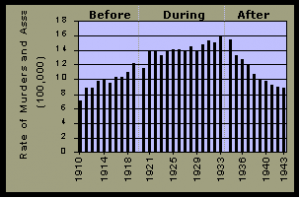

Unfortunately, Prohibition backfired enormously. Organized crime reached its heyday during this period as the illegal trade of alcohol fueled gang efforts across the nation. The table below displays the dramatic increase in murder and assault rates with a firearm during the time of national Prohibition in America (1920-1933).

Institutions across the country, notably police forces, suffered greatly during the period. Many of the people responsible for enforcing the laws of Prohibition were personally against the policy, blurring the lines between who was right and who was wrong. Similar to The Wire in this way, morally good policemen were considered pariahs by their own institution for not following orders and equally disdained by criminals who associated them with the ills of bureaucratic America. All in all, the era was an unfortunate and unsuccessful one for law enforcement, as “barely 5% of smuggled liquor was stopped by the Feds. And in the end, it didn’t matter. Whatever couldn’t be imported was simply manufactured here in the states.[3]Early efforts of the “War on Drugs” proved to be futile, not too different from efforts of today.

The “War on Drugs” as we know it, commenced in June, 1971, as Richard Nixon declared in a press conference that drugs were “public enemy number one in the United States.” We begin our timeline of the “War on Drugs” in the United States a few years before this proclamation, beginning with its motivating events and continuing through the latest developments in the 21st-century.

Late 1960s: In late 1960s recreational drug use becomes fashionable among young, white, middle class Americans. The social stigmatization previously associated with drugs lessens as their use becomes more mainstream. Drug use becomes representative of protest and social rebellion in the era’s atmosphere of political unrest.

July 14, 1969: In a special message to Congress, President Richard Nixon identifies drug abuse as “a serious national threat.” Citing a dramatic jump in drug-related juvenile arrests and street crime between 1960 and 1967, Nixon calls for a national anti-drug policy at the state and federal level.

October 27, 1970: Congress passes the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act. This law consolidates previous drug laws and reduces penalties for marijuana possession. It also strengthens law enforcement by allowing police to conduct “no-knock” searches. This act includes the Controlled Substances Act, which establishes five categories (“schedules”) for regulating drugs based on their medicinal value and potential for addiction.

June, 1971: Nixon declares war on drugs. At a press conference Nixon names drug abuse as “public enemy number one in the United States.” During the Nixon era, for the only time in the history of the war on drugs, the majority of funding goes towards treatment, rather than law enforcement.

January, 1972: The Office of Drug Abuse Law Enforcement is founded. The Nixon Administration creates the Office of Drug Abuse Law Enforcement (ODALE) to establish joint federal/local task forces to fight the drug trade at the street level.

July 1973: Nixon creates the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to coordinate the efforts of all other agencies. The DEA consolidates agents from the BNDD, Customs, the CIA and ODALE.

September, 1975: Ford administration releases White Paper on Drug Abuse. The Domestic Council Drug Abuse Task Force releases a report that recommends that “priority in Federal efforts in both supply and demand reduction be directed toward those drugs which inherently pose a greater risk to the individual and to society.” The White Paper names marijuana a “low priority drug” in contrast to heroin, amphetamines and mixed barbiturates.

November 1975: Colombian police seize 600 kilograms of cocaine — the largest seizure to date — from a small plane. Drug traffickers respond with a vendetta, killing 40 people in one weekend in what’s known as the “Medellin Massacre.” The event signals the new power of Colombia’s cocaine industry, headquartered in Medellin.

1976: Former Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter campaigns for president on a platform that includes decriminalizing marijuana and ending federal criminal penalties for possession of up to 1 ounce of the drug.

August, 1976: Anti-drug parents’ movement begins. Troubled by the presence of marijuana at her 13-year old daughter’s birthday party, Keith Schuchard and her neighbor Sue Rusche form Families in Action, the first parents’ organization designed to fight teenage drug abuse. Schuchard writes a letter to Dr. Robert DuPont, then head of the National Institute of Drug Abuse, which leads DuPont to abandon his support for decriminalization.

1979: Carlos Lehder, co-founder of the Medellin cartel, purchases a 165-acre island in the Bahamas. Small planes transporting drugs from Colombia to the United States use the island to refuel. Operations continue on the island until 1983.

1981-1982: The Medellin cartel rises to power. The alliance includes the Ochoa family, Pablo Escobar, Carolos Lehder and Jose Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha. The drug kingpins work together to manufacture, transport and market cocaine.

1981: The United States and Colombia ratify a bilateral extradition treaty. When Reagan assumes office and prioritizes the war on drugs, extradition becomes the greatest fear of the Colombian traffickers.

January, 1982: In the United States, Vice-President George H.W. Bush combines agents from multiple agencies and military branches (DEA, Customs, FBI, ATF, IRS, Army, and Navy) to form the South Florida Drug Task Force, Miami being the main entry point at the time.

March, 1982: Pablo Escobar is elected to the Colombian congress; he gained support by building low-income housing, doling out money in Medellin slums and campaigning with Catholic priests. He’s driven out of Congress the following year by Colombia’s minister of justice.

March, 1982: Largest cocaine seizure ever raises U.S. awareness of Medellin cartel. The seizure of 3,906 pounds of cocaine, valued at over $100 million wholesale, from a Miami International Airport hangar permanently alters U.S. law enforcement’s approach towards the drug trade. They realize Colombian traffickers must be working together because no single trafficker could be behind a shipment this large.

1982: Panamanian leader Gen. Manuel Noriega allows Pablo Escobar to ship cocaine through Panama ($100,000 per load).

1984: Nancy Reagan launches her “Just Say No” anti-drug campaign.

July, 1984: The Washington Times publishes a story about DEA informant Barry Seal’s infiltration of the Medellin cartel’s operations in Panama. The story shows that Nicaraguan Sandanistas are involved in the drug trade. As a result of Seal’s evidence, a Miami federal grand jury indicts Carlos Lehder, Pablo Escobar, Jorge Ochoa and Jose Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha. (In February 1986, Seal is assassinated in Baton Rouge, La., by gunmen hired by the cartel.)

1985: Colombia extradites drug traffickers to the United States for the first time. U.S. officials discover that the Medellin cartel has a “hit list” that includes embassy members, their families, U.S. businessmen and journalists.

1985: Crack explodes in New York. Crack, a potent form of smokeable cocaine developed in the early 1980s, begins to flourish in the New York region. A November 1985 New York Times cover story brings the drug to national attention. Crack is cheap and powerfully addictive and it devastates inner-city neighborhoods.

Mid-1980s: Because of the South Florida Drug Task Force’s work, cocaine trafficking slowly changes transport routes. The Mexican border becomes the major point of entry for cocaine headed into the United States.

October 1986: Reagan signs the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which appropriates $1.7 billion to fight the drug war. The bill also creates mandatory minimum penalties for drug offenses, which are increasingly criticized for promoting significant racial disparities in the prison population because of the differences in sentencing for crack and powder cocaine. Possession of crack, which is cheaper, results in a harsher sentence; the majority of crack users are lower income.

February 1987: In February, Carlos Lehder is captured by the Colombian National Police and extradited to the United States, where he’s convicted of drug smuggling and sentenced to life in prison without parole, plus an additional 135 years.

May 1987: After receiving personal threats from drug traffickers, the justices on the Colombian Supreme Court rule by a vote of 13-12 to annul the extradition treaty with the United States.

1988: Carlos Salinas de Gortari is elected president of Mexico, and President-elect George H.W. Bush tells him he must demonstrate to the U.S. Congress that he is cooperating in the drug war. This process is called certification.

1989: President George H.W. Bush creates the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) and appoints William Bennett as his first “drug czar.” Bennett aims to make drug abuse socially unacceptable. That same year, Forbes magazine lists Pablo Escobar — known for his “bribes or bullets” approach to doing business — as the seventh-richest man in the world.

December 1989: The United States invades Panama. Gen. Manuel Noriega surrenders to the DEA on Jan. 3, 1990, in Panama and is sent to Miami the next day. In 1992, Noriega is convicted on eight counts of drug trafficking, money laundering and racketeering, and sentenced to 40 years in prison.

January 20, 1990: Bush proposes to add an additional $1.2 billion to the budget for the war on drugs, including a 50% increase in military spending.

1991: The Colombian assembly votes to ban extradition in its new constitution. Pablo Escobar surrenders to the Colombian police the same day. He is confined in a private luxury prison, though reports suggest that he travels in and out as he pleases. When Colombian authorities try to move Escobar to another prison in July 1992, he escapes.

1992: Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari issues regulations for DEA officers in his country. The new rules limit the number of agents in Mexico, deny them diplomatic immunity, prohibit them from carrying weapons, and designate certain cities in which they can live.

November 1993: President Clinton signs the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which increases the amount of trade and traffic across the U.S.-Mexican border. This makes it more difficult for U.S. Customs to find narcotics moving across the border.

December 1993: Pablo Escobar, in hiding since mid-1992, is found by Colombian police using American technology that can recognize his voice on a cell phone call and estimate his location. He tries to flee but is killed.

1993 – With the Medellin cartel dismantled, a group of traffickers from the Colombian city of Cali rise in power.

May 1995: The U.S. Sentencing Commission releases a report that acknowledges the racial disparities for prison sentencing for cocaine versus crack. The commission suggests reducing the discrepancy, but Congress overrides its recommendation for the first time in history.

1996 – Colombia police and the DEA dismantle the Cali cartel. In Mexico, smuggler Osiel Cardenas takes over the Gulf Cartel on the Texas border. He later recruits elite soldiers in Mexico’s army to form the cartel’s feared armed wing, the Zetas.

August 2000: President Bill Clinton gives $1.3 billion in aid to Plan Colombia, an effort to decrease the amount of cocaine produced in that nation. The aid supports the aerial spraying of coca crops with toxic herbicides, and also pays for combat helicopters and training for the Colombian military.

2003: In February, three Americans — contracted by the Pentagon to help with Colombia’s anti-drug effort — are taken hostage by guerrilla fighters after their surveillance plane crashes. In April, the Illicit Drug Anti-Proliferation Act is enacted, which targets ecstasy, predatory drugs and methamphetamine.

2004: Along with the State Department and the Department of Defense, the DEA announces its involvement in the U.S. Embassy Kabul Counternarcotics Implementation Plan. It’s designed to reduce heroin production in Afghanistan, the world’s leading opium producer.

January, 2006: Authorities announce the discovery of the longest cross-border tunnel in U.S. history, the work of what they call a well-organized and well-financed drug-smuggling group. The half-mile long tunnel links a warehouse in Tijuana, where about two tons of marijuana was seized, to a warehouse in the United States, where 200 pounds of the drug were found.

III. THE SELLERS

Since such a significant part of the narrative in The Wire focuses on the drug trade, and since, arguably, being presented with such an intimate look at the organization and operation of the Barksdale drug network is for many viewers one of the chief pleasures of watching the show, this section will contextualize the supply side of the drug trade, providing an account of the real situation of drug dealing in America. Furthermore, it will also include a discussion of the drug business in Baltimore, which should be particularly relevant in the context of the series.

Economic Rationale

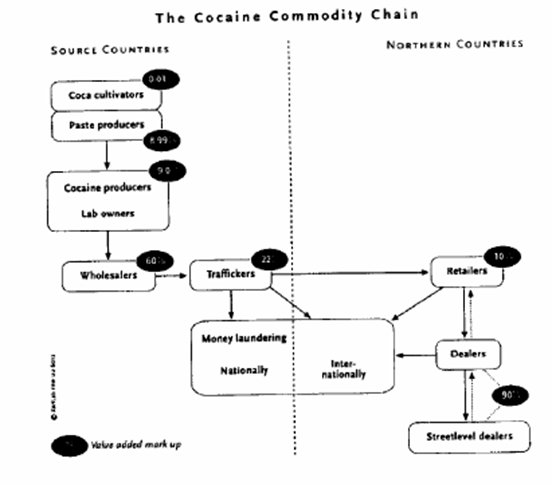

The sale of illicit drugs continues to plague communities across the United States and is largely resistant to enforcement efforts precisely because it is such a lucrative business. Preparing the drugs is a very inexpensive process, but the profit margins that it generates are enormous. The huge value added by the actual trafficking and distribution cycle is evident in the disparity between the street price of the drugs in the source country, as compared to their sale price in the United States. Processed cocaine costs $1500 dollars per kilo in Colombia, but is old on the streets of New York for as much as $66,000 a kilo. Heroin can be bought for $2,600 per kilo in Pakistan, but its retail price on American streets is more than $130,000 a kilo.[1]

Former DEA agent Robert Stutman puts the profitability of the drug industry in context: “The average drug trafficking organization could afford to lose 90% of its profit and still be profitable. Now think of the analogy. GM builds a million Chevrolets a year. Doesn’t sell 900,000 of them and still comes out profitable. That is a hell of a business, man. That is the dope business.” And this is bad news for the war on drugs. As economist Ken Dermota observes, “no other product returns 20,000 percent on investment, divided among various middlemen along the way. So long as U.S. customers are willing to pay 200 times the real price of a manufactured good, some poor Latino with an urge to get ahead is going to make sure that it gets to the streets of New York.”[2]

It is thus ironic to think that the price difference, and consequently its profitability, derives precisely from its illegality. It is the risk incurred at every step in the operation that adds value to the final retail price of the drug. As the origin of the Avon’s drugs is starting to gain prominence in the show – especially now that there is a problem with the supply – and as the drug trade is presented in a more globalized context with the inclusion of the Greeks, the Dominicans and the Columbians, it is worth looking at the global cycle of drug trafficking in a wider context. How do the cocaine and heroin reach Avon’s crew, how are they distributed, and who carries the risks?

The Cycle of Trafficking

The majority of coca leaves are harvested in Latin America, particularly in Colombia, Bolivia and Peru. Today, cocaine is South America’s second most important export after petroleum, and in Colombia, cocaine exports are more than 90% of the country’s legal exports. The trafficking of illegal narcotics accounts for a significant percentage of these countries’ Gross Domestic Product, and also generates a substantial amount of employment opportunities. Around 450,000 to 500,000 Andeans work in all stages of the cocaine business – harvesting, refining, transportation, etc – and employment in the cocaine industry accounts for 2.5 to 3.0 percent of the work force in Peru and Bolivia, and 1.0 to 1.5 percent in Colombia. In the interest of comparison, it has been estimated that in the United States, 200,000 people (or 0.15 percent of the labor force) work in some capacity in the cocaine trafficking chain.[3]

The diagram below presents a schematic overview of the cycle of cocaine trafficking (sorry for the bad quality of the image, it was scanned from a book):

Farmers harvest the coca leaves and make them into paste in their own rustic kitchens, before selling them to representatives of the different drug organizations in special “paste markets.” The paste is then transported to refining labs across the country, where it is processed into cocaine hydrochloride (the actual drug sold on the streets) and packaged accordingly. Generally, the resulting packages are flown from airstrips near the labs to the coast, where they leave the country by boat – especially the so-called “go-fast” motorboats that can carry up to 6 tons of cocaine – which transport the cocaine to Mexico, in order to smuggle it across the border into the United States. Alternatively, some drug organization also use “mules” who transport the pellets inside their own bodies. The Mexican traffickers can charge up to 50% of the product in exchange for its distribution in the United States. Their share is distributed by U.S.-based members of the cartel, while the vast remainder of the merchandise is sold to the Colombian and Dominican distributors, mostly on the East Coast, who further pass it on to smaller-scale distributors like Avon Barksdale or Proposition Joe for street retail.[4]

The trafficking of heroin follows a very similar pattern, and also originates as a crop – the poppy seed – harvested by farmers in developing countries, particularly Afghanistan, Myanmar and Pakistan. The crops are bought by “brokers”, usually community elders, who further sell it to drug organization that refine the substance and arrange its transportation. Heroin is usually shipped to a transit country – usually Mexico or Canada – and then introduced into the United States by couriers or “mules”, many of whom transport it inside their own bodies, by swallowing pellets of drug-filled condoms. Once in the United States, the heroin is distributed down the chain similarly to the way cocaine is, with distributors on the East Coast, especially African and Asian immigrants, passing the merchandise on to street-level networks.[5]

The Structure of Drug Networks

The organization and hierarchy characterizing each network of drug dealers varies according to the size and scope of their business. Large scale organizations, especially international drug traders like the Arellano Felix cartel in Mexico, are structured just like modern corporations, with different levels of management and enormous cash funds that oil the wheels of the machinery.[6] Smaller scale drug distribution networks, on the other hand – like the one depicted by Bourgois in his ethnography – operate more locally, and usually sell their merchandise from improvised retail hubs like the Game Room described in the book.

The Barksdale organization would probably fall somewhere in the middle in terms of scale, since it does boast a complex network of distribution with various levels of management, yet it does not appear to have constant and reliable access to a direct drug source, and thus seems unaffiliated with the major international importers. However, in reality, vertical integration is highly unfeasible and also rather undesirable in the industry of drug trafficking, since each chain adds a level of insulation to the cycle, and the concentration of all risk in the hands of one major actor would not be sustainable in this trade, as Pablo Escobar fatefully realized in 1993.[7]

Drug Dealing in Baltimore

In an article for the Bureau of Justice Assistance, Edward Burns, one of the co-writers of the show and a veteran Baltimore police detective, explains how in Baltimore, inner-city street gangs “control drug distribution from street-level consumption to bulk wholesale.” Dealing mainly in heroin and cocaine, the gangs maintain their hegemony by exercising “systematic violence” in order to reinforce their territorial domination and expand their areas of influence. Burns explains the operation of these inner-city drug networks:

“After the base of operation is secured, a gang focuses on optimizing the territory for the sale of street-grade heroin and cocaine. Under the leader’s direction, the hardcore gang members—soldiers whose loyalty to the leader is expected to be absolute—secure drug stash houses and paraphernalia for the operation and recruit the expendable dealers, runners, touts, and lookouts. As the gang’s profits grow, more expendable, lower-level members are recruited, and the gang’s size and influence expand.

The gang leader maintains dominance over the membership by a mixture of rewards and violence, with an emphasis on the latter. The leader is the focal point of the gang’s activities, the final arbiter of disputes, the source of spending money and bail, and the receiver and dispenser of information. He or she manipulates gang members by testing loyalties, determining status, and keeping members off guard and subservient to his or her will—perfecting a totalitarian form of control.

While the gang secures the lines of distribution, the leader controls the flow of drug revenues and maps out supply lines. The gang leader is in contact with established local leaders of other gangs and with former gang leaders who now work in the criminal underworld and no longer require the services of the gang. These more experienced gangsters coach the younger criminal in matters such as hiring lawyers, hiding money, creating communication networks, and researching police investigative procedures and ways to avoid them.”[8]

In this context, it is interesting to note that, judging from the description provided by Burns, the one who would clearly emerge as the leader of the Barksdale organization is Stringer, not Avon. Stringer is the one who fulfills most of these managerial functions, as well as being in charge of the supply chains, and while he does need Avon’s okay to implement his ideas, we are starting to see more and more clearly that ultimately, he can afford to disobey Avon and implement his own plans. Thus, it will be exciting to follow the power struggle between the two characters, as surely things will heat up soon for the leadership of the Barksdale crew.

Burns also notes that systematic violence is directly associated with the operation of these inner-city drug-dealing gangs, who often commit strategic murders to establish their dominance in a certain area. These murders are openly claimed by the gang, strengthening its reputation on the streets.[9] Drug-related violence has been classified according to three subtypes: psychopharmacological (violence caused by the effects of the drug itself), economic compulsive (in order to get money to purchase the drug) and systemic (to “protect turfs, contracts, or reputation”). To put this in context, in New York City, for instance, a recent study has found that 74% of drug-related homicides were systemic – a clear indication of the link between gang rivalry and the workings of the drug trade.[10]

The Governor’s Office of Crime Control and Prevention and the University of Maryland estimate that 1,800 Baltimore residents belong to 45 known street gangs in the city.[11]

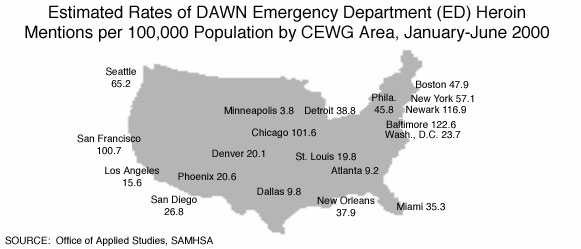

The trafficking of illegal drugs is particularly severe in inner-city Baltimore, as compared to national statistics. It has infamously become known as the heroin capital of America, with an estimated 50,000 addicts, a rate of use substantially higher than in other major cities (see map). A recent report by the Mayor’s Office revealed that the city’s informal economy turns a profit of $872 million of previously uncounted income. If the U.S. Census Bureau is right in estimating that in 2002 “accommodation and food service sales” in Baltimore totaled about $1 billion, it means that Baltimoreans spent almost the same on food and lodging as they did on illicit drugs.[12]

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the crime figure who served as the greatest inspiration for the writers of The Wire is “Little Melvin” Williams, a West Baltimore drug kingpin who is largely accredited with the popularization of heroin in the 1960s. Interestingly, it was Edward Burns who arrested Williams in 1984, when he was working as a detective for the Baltimore Police Department, while David Simon, in his capacity as a reporter for The Baltimore Sun, interviewed him in prison immediately after his capture. Twenty years later, their paths are still intertwined, as Williams apparently played a character on The Wire in the later seasons, and the three men still regularly meet for lunch in Little Italy.[13]

IV. THE BUYERS

According to the Office of National Drug Control Policy, Americans spend more than $64 billion on illegal drugs annually, making drug trafficking the second most lucrative activity in the service sector, after the hospitality business.[1] More than two thirds of this amount is spent on cocaine, which means that on average, more is spent nationally on cocaine than on airline tickets, gas utilities or magazines and newspapers.[2]

The Use of Illicit Drugs in the United States

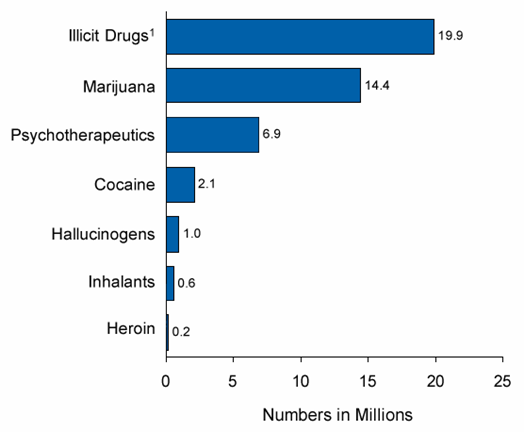

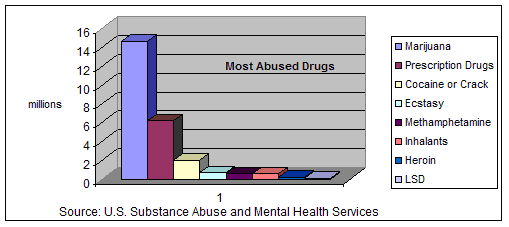

But what exactly is the scope of drug use in America? How many people are using illicit drugs, both recreationally and frequently, and who are they? Recent statistics from the Department of Health indicate that in 2007, an estimated 19.9 million Americans aged 12 or older were current drug users, meaning that “they had used an illicit drug during the month prior to the survey interview.” This represents 8.0 percent of the population, a rate very close to the 2006 estimate of 8.3 percent. Marijuana was the most frequently used drug, with 14.4 million current users, followed by psychotherapeutic drugs used nonmedically, with 6.9 million, cocaine with 2.1 million, and hallucinogens with 1.0 million users.

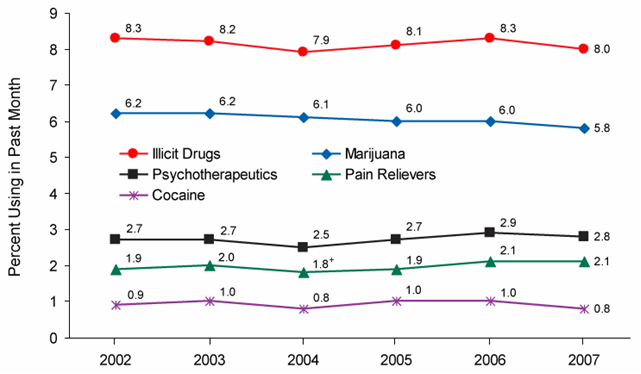

The 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicates that the rate of illegal drug use in the United States has been fairly stable throughout our decade, a constancy that casts doubt on the success of the various enforcement measures and outreach campaigns undertaken as part of the war on drugs:

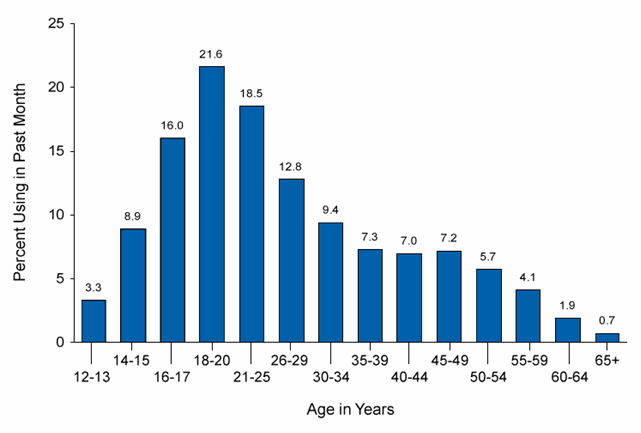

Who are these 19.9 million users? Most of them are young adults, aged 18 to 25, followed closely by older teens. Among youths aged 12 to 17, an average of 9.5 percent reported being current users. The rate of use for this segment of the population has decreased substantially, however, compared to the 11.6 percent of 12-17 year olds estimated to be using drugs in 2002.

Men are approximately twice as likely to consume illegal drugs than are women. In 2007, 10.4 percent of the male population reported using illicit drugs, as compared to only 5.8 percent for females.

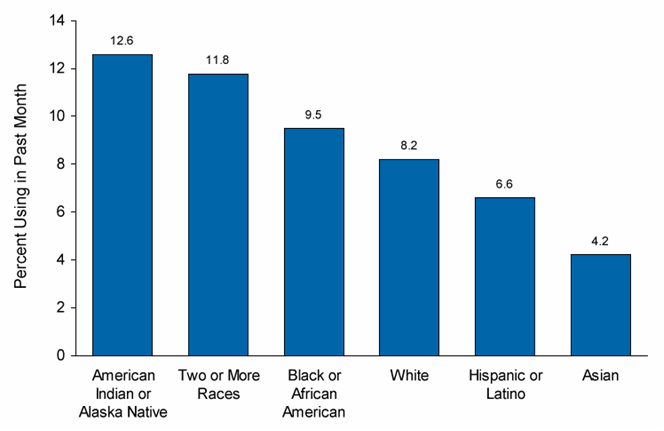

Given the strong thematic emphasis on race and ethnicity that underpins the narrative of The Wire, it is also enlightening to look at the statistics regarding the ethnic background of America’s drug users. The same report from the Office of National Drug Control Policy indicates that the rate of drug use is highest not among blacks, as perhaps is suggested by various representations in popular culture, but among Native Americans, 12.6 percent of whom reported consuming illegal drugs. The rate of use among African Americans is 9.5 percent, which is not much higher than that of Caucasians, with 8.2 percent. [3]

Source of tables: 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health

The effects of drug use

The different types of illicit drugs vary in terms of the way they affect our physical and mental health. In order to better understand the instances of drug use presented in The Wire, it is most constructive to discuss the particularities of cocaine, crack and heroin. Also, crack is central to the community depicted by Philippe Bourgois in his ethnography, and the trafficking of this drug has heavily influenced the structure and operation of drug networks in America ever since it boomed in the late 80s.

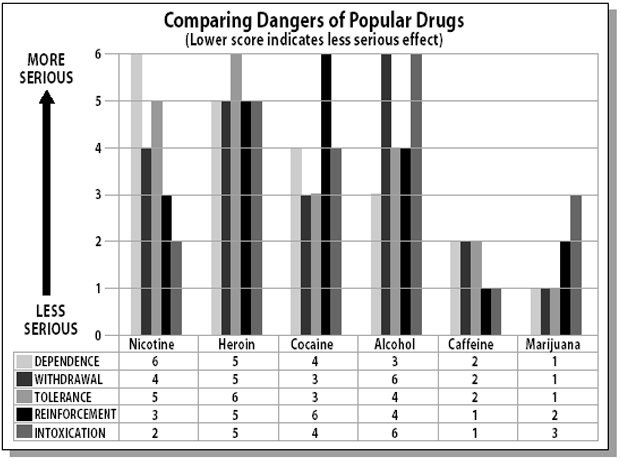

Source: CommonSenseForDrugPolicy.org

Cocaine comes from a substance found in the leaves of the coca plant, originating mainly from Latin America. The coca leaves are made into a paste and heated with hydrochloric acid to produce cocaine hydrochloride. It is generally sold in powder form, which can vary in purity and is often mixed with other substances like lactose, mannitol, or amphetamines. Cocaine increases focus and energy levels, quenches the appetite and triggers all the symptoms of the “fight-or-flight syndrome”, heightening the heart rate and blood pressure. Long term or heavy use can result in depression, anxiety, chronic fatigue, mental confusion, paranoia, and even death caused by convulsions.[4]

Crack is derived from the cocaine base before it has been neutralized by the hydrochloric acid. This base comes in a rock crystal that is processed with ammonia or sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) and water, and then heated to produce the vapors which are smoked in special pipes. The term “crack” originates from the crackling sound that the rock makes as it is being heated. Because cracked is consumed by smoking it, the user gets a very quick and overwhelming high in less than 10 seconds. This, coupled with the relative low cost of purchasing it, has made crack one of the most insidious and menacing drugs in inner-city American communities.[5]

Heroin is an extremely addictive powder or tar-like opiate, derived through the chemical alteration of morphine obtained from poppy seeds. It stimulates the brain’s pleasure systems and decreases sensitivity to pain, producing a “rush of pleasure” and a “dreamy, pleasant, drowsy” state of being. Heroin can be injected into a vein (a practice denoted “mainlining”) or a muscle, smoked in a pipe, mixed with marijuana or tobacco, inhaled through a straw or snorted as powder. It is one of the most addictive substances ever known, as tolerance develops extremely easily, and thus heroin withdrawal is a particularly terrible condition.[6]

It has long been debated whether drug addiction is a biological disease or a sign of an individual’s moral weakness. Especially after the crack epidemic of the 1980s and the increase in crime resulting from it, drug addicts were socially stigmatized, and the public budget for addiction treatment fell substantially. Recently, however, the notion that addition is a biological condition has gained a strong foothold in the medical community, and researchers have now proved that a person’s genes, as well as their environment and development, are significant factors in determining each individual’s predisposition to addiction.[7]

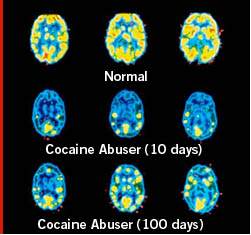

The PET scan below shows images of a healthy brain, the brain of a cocaine addict 10 days a fter the last dose, and, respectively 100 days after the last dose. It is evident from the scan that even after 100 days of not consuming cocaine, the brain’s metabolism is still substantially decreased in the front lobe, an area which regulates impulsive and repetitive behavior, planning and organizing activities, and critical thinking.

fter the last dose, and, respectively 100 days after the last dose. It is evident from the scan that even after 100 days of not consuming cocaine, the brain’s metabolism is still substantially decreased in the front lobe, an area which regulates impulsive and repetitive behavior, planning and organizing activities, and critical thinking.

Nevertheless, despite the increased attention given to treatment and rehabilitation initiatives in the past years, statistics show that there is a considerable “treatment gap” in the United States between the number of people seeking help and the available programs. According to the Office of National Drug Control Policy, half of the 3.6 million drug users who need treatment cannot afford it or do not know where they can receive it.[8]

Source: Brookhaven National Laboratory

V. THE ENFORCERS

While watching The Wire we see the show from two main perspectives: The Dealers (i.e. the Barksdale Crew) and the members of the Baltimore Police Department that try to thwart their efforts. This section will focus on the law enforcement side of the drug game. It will include a look at how America fights the War on Drugs on the national and local level. Since The Wire takes place in Baltimore we will use Baltimore as the model for local law enforcement of illegal drugs.

The National Drug Policy

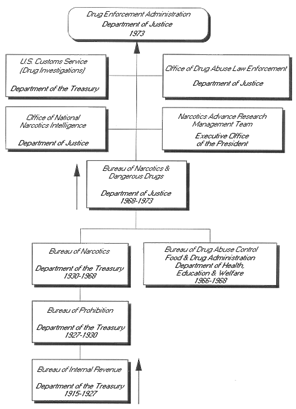

The “War on Drugs” has been in ongoing battle in America since Prohibition, however, it was not until President Richard Nixon signed Reorganization Plan No. 2 on March 28, 1973 that the United States government officially sanctioned a law agency devoted specifically to combat the use of illegal drugs in America. As a direct result of Reorganization Plan No. 2 the Drug Enforcement Administration was officially established on July 1, 1973 and since that day the DEA (in conjunction with the FBI) has served as the lead agency for the enforcement of the United States drug policy both at home and abroad.

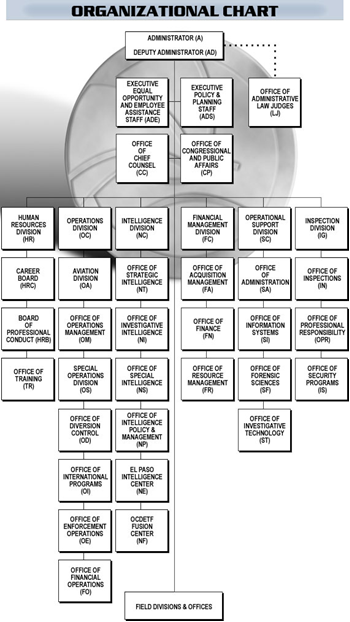

Below is a diagram that charts the genealogy of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA):

The Mission Statement of the DEA is as follows:

“The mission of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) is to enforce the controlled substances laws and regulations of the United States and bring to the criminal and civil justice system of the United States, or any other competent jurisdiction, those organizations and principal members of organizations, involved in the growing, manufacture, or distribution of controlled substances appearing in or destined for illicit traffic in the United States; and to recommend and support non-enforcement programs aimed at reducing the availability of illicit controlled substances on the domestic and international markets.” (DEA Website)

The DEA is lead by a Presidentially-appointed Administrator of Drug Enforcement and a Deputy Administrator who is also appointed by the President, both choices must be approved by the US Senate. The Administrator of Drug Enforcement reports directly to and works closely with the Attorney General in an effort to fight the drug trade in America and abroad. Working directly under the Administrator of Drug Enforcement are the Chief of Operations, the Chief Inspector, and three Assistant Administrators for Operations Support, Intelligence, and Human Resources. Together these seven positions encompass the highest echelon of drug enforcement in the United States. Under their supervision are a team comprised of 10,759 total employees including 5,235 Special Agents and a budget exceeding 2.3 billion dollars.

Former DEA Administrators:

Below is a chart showing the positional hierarchy of the DEA

Training and Tactics

On April 28, 1999 the DEA opened a new training facility aimed at training students to be a part of the best drug enforcement team on the planet. The mission of the DEA’s Office of Training is as follows:

“The mission of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) Office of Training is to develop, deliver and advocate preeminent law enforcement and non-law enforcement training to DEA personnel and appropriate federal, state, local, and foreign law enforcement counterparts. The goal of this training is to improve student’s individual and organizational performance and assist them in achieving either DEA’s mission and performance goals or those of their assigned organization.” (DEA Website)

At DEA Basic Training a class of forty to fifty Basic Agent trainees are put through a six-teen week program that combines rigorous mental and physical training. In addition to eighty-four hours of physical fitness and defensive tactics training and 122 hours of firearms training, Basic Agent trainees must maintain an average of at least eighty percent on all academic exams. If a Basic Agent trainee completes the training he or she is sworn in as DEA Special Agent and assigned to a field office around the country.

Once placed in a DEA Field Office, Special Agents become soldiers in the War on Drugs. The DEA’s main charge is to enforce the Controlled Substances Act. (http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/pubs/csa.html) Special Agents enforce this act by working closely with local authorities on investigations, stakeouts, and raids of suspected drug cites. Another way in which the DEA accomplishes its goal is with MET’s or Mobile Enforcement Teams. MET’s are small specialized squads that focus on rural and small urban areas that may lack local law enforcement resources. MET’s work with local law enforcement to attack drug trafficking and the resulting violence.

Results

There are mixed reviews when it comes to the results of the DEA’s efforts. In 2005 the DEA made 29,005 domestic arrests and seized 640 kilograms or Heroin, 118,311 kilograms of Cocaine, and 283,344 kilograms of Marijuana as well as 1.4 billion dollars in drug related assets. While these numbers seem staggering, and in fact they are, even more staggering is the fact that the White House’s Office of Drug Control Policy claims that all of the seized assets claimed by the DEA add up to only one percent of the total amount Americans spent on illegal drugs in 2005.

|

Calendar Year |

Number of Arrest |

|

2007 |

27,780 |

|

2006 |

29,800 |

|

2005 |

29,005 |

|

2004 |

27,053 |

|

2003 |

28,549 |

|

2002 |

30,270 |

|

2001 |

34,471 |

|

2000 |

39,743 |

|

Calender Year |

Cocaine kgs |

Heroin kgs |

Marijuana kgs |

Methamphetamine kgs |

Hallucinogens dosage units |

|

2007 |

96,713 |

625 |

356,472 |

1,086 |

5,636,305 |

|

2006 |

69,826 |

805 |

322,438 |

1,711 |

4,606,277 |

|

2005 |

118,311 |

640 |

283,344 |

2,161 |

8,881,321 |

|

2004 |

117,854 |

672 |

265,813 |

1,659 |

2,261,706 |

|

2003 |

73,725 |

795 |

254,196 |

1,678 |

2,878,594 |

|

2002 |

63,640 |

710 |

238,024 |

1,353 |

11,661,157 |

|

2001 |

59,430 |

753 |

271,849 |

1,634 |

13,755,390 |

|

2000 |

58,674 |

546 |

331,964 |

1,771 |

29,307,427 |

As the War on Drugs progresses the DEA continues to fight suppliers, smugglers, dealers, and buyers in an effort to stem the spread of the drug trade in America.

Drug Enforcement in Baltimore

|

State Facts |

2007 Federal Drug Seizures |

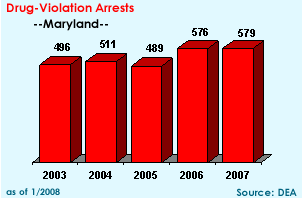

According to the DEA, Maryland has the has the third-highest rate of violent crime in the entire country, and as anyone who has watched The Wire knows, the Baltimore drug trade contributes greatly to the statistic.

In an article published for the Bureau of Justice Assistance retired Detective Edward Burns lays out successful methods for enforcing drug laws and prosecuting the people that break them, specifically gangs and gang leaders. Burns’ insight is especially helpful for out purposes because he not only worked for the BPD for twenty years, but he is also a co-creator of The Wire.

In his article Burns states:

“The proposed approach to combating gangs is based on the idea that the gang is an instrument of the leader’s will—a will that often requires violence to satisfy personal ambitions. An investigative goal is to develop conspiracy cases from evidence obtained by turning the gang’s violence inward upon vulnerable gang members. This is done by pitting the sensible against the indiscriminately violent and by turning the many troops against the one corrupt gang leader.”

Law enforcement officials are able to turn the troops against their leader because, as Burns states, many gang members (i.e. Wallace and D’Angelo) are against violence. This approach allows law enforcement officials to take the unrest that violence creates within the gang and use it against the gang leader.

Burns classifies law enforcement investigations into two distinct categories: Covert and Overt. Burns defines the Covert phase of the investigation as, “identifying the gang’s members, detecting its victims and violent acts, learning its reputation, and developing an informant to observe and record the gang’s characteristics and activities over time.” The Wire focuses mostly on the Covert phase of the investigation. This is the type of work that is being done on the detail: setting up DNR’s and wiretaps, getting information from Confidential Informants (Bubbles), and taking pictures of drug trafficking (this is what Herc and Carver do on the rooftops).

Once the Covert phase of the investigation is finished the investigation moves into the Overt phase. This is when, as Burns explains, “the targeted gang members are placed in legal jeopardy in a highly structured interview situation designed to change their allegiance from the gang to the investigative team.

Burns tells us that the investigators accomplish the switch in allegiance in one of three ways: controlled arrests, interviews with randomly arrested gang members, and the use of grand juries as investigative tools.

Controlled arrests are used when they can be done without taking too much time away from the existing investigation. A controlled arrest involves arresting a gang member who already has a criminal past or who is currently on parole – this increases the legal stakes for the gang member and makes it more likely that he will turn on the leader for a reduced sentence. As Burns puts it, “An arrest for possession of a controlled, dangerous substance when the subject is already on parole also isolates a gang member and creates uncertainty within the gang.” We saw this at the end of the first season of The Wire when D’Angelo agreed to cooperate with the police before his mother talked him out of it.

The second method Burns discusses is interviews of randomly arrested gang members. “For large, well-established gangs, the likelihood is high that at any time some members may be incarcerated. Because gang members know that jail time is a reality, they may feel vulnerable to prosecution if witnesses and/or evidence exist that could link them to a crime.” With uncertainty about prosecution, gang members may be talked into cooperating with the government to avoid jail time. We see this at the end of the first season of The Wire when Orlando agrees to work with the police after he is arrested for buying cocaine.

The third method of the Overt investigation is using the grand jury as an investigative tool, which Burns explains as: “Police can place a gang member in a vulnerable position without expending a great deal of time or investigative energy. The threat of a perjury or contempt sanction, juxtaposed with a promise of immunity and a chance to escape a losing proposition (i.e., long jail time), makes the gang member feel uncertain and insecure—an ideal situation for the interviewer. After a gang member is placed in this vulnerable position, he or she is confronted in a pre-grand-jury interview by an investigator and prosecutor who work as a team.”

Police Gang Units

An important way, Burns tells us, that the Baltimore Police Department fights the War on Drugs is through the creation of Police Gang Units. These units are small self-contained units that operate closely with the Homicide unit so that patterns can be noticed gang-related (and therefore drug related) homicides. Furthermore, the Gang Unit should work closely with a specific prosecutorial team so that the grand jury can be used to its full advantage.

Policy

While watching The Wire, we have often heard of drug trafficking and the lifestyle that goes with it referred to as The Game. As in any game you need players, officials, and a set of rules that govern play. If the dealers and buyers are the players in the game and the enforcement agencies are the officials then American Drug Policy are the rules that govern them. This section will discuss America’s Drug Policy and how America governs drug trafficking.

The Controlled Substances Act

Most of America’s drug policy can be summed up by the Controlled Substances Act or Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act which was made law by the US Congress in 1970. The Controlled Substances Act compartmentalizes drugs into five different categories or “schedules” that rate drugs based on their use for medicinal purposes and their addictive capabilities. Drugs with no medicinal purposes and a likelihood of abuse are given a schedule one rating while drugs with an accepted medicinal purpose and a low likelihood of abuse are given a schedule five rating. The CSA was amended in 1978 to allow Drug Enforcement officials to seize all assets gained through selling illegal drugs.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act

Another important piece of US Drug Policy is the Anti-Drug Abuse Act that was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan in 1986. The bill allocated 1.7 billion dollars for aid to the War on Drugs. While a large chunk of the money was set aside for drug education and treatment the bill was controversial because it introduced mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenders. This means that one kilogram of heroin or five kilograms of cocaine was punishable with at least ten years in prison. However, five grams of crack cocaine is punishable by a mandatory minimum of five years in prison. This law has been criticized since its inception over the disparity between the mandatory minimums for powder cocaine (which is used in more affluent areas) and crack cocaine (which is used in more poverty stricken areas). (PBS)

VI. REFORM

The legalization of drugs in the United States is quite an interesting issue that is still going on today. Alcohol was banned in the eighteenth amendment of 1919, only to be repealed by the twenty-first amendment of 1933. This is a great example of a drug that was deemed socially incorrect to use at first but then was still widely used upon prohibition, ultimately leading to the legalization of the drug. The prohibition of drugs in the U.S. is based on social perceptions and the drugs ability to not only affect the person whom consumes the drug, but the people around them as well. Drugs in the past have been deemed illegal when society fears there would be a high risk of abuse of that drug if no regulation were in place. Both alcohol and tobacco are drugs that are highly addictive and detrimental to society, yet they are still legal to use and sell in the United States. There can be solid arguments for both the ban and legalization of drugs in the U.S. but there are risks associated with both sides.

Looking at the reason why alcohol was legalized can teach us a great deal about the problems we are facing with marijuana today. Put simply, individuals in our society have different views towards drugs, which are the reason for conflicts concerning the legalization of drug. After alcohol was banned, crime rates increased as many U.S. citizens continued using the drug. In 2007, “marijuana arrests actually increased 18 percent in California…while all other arrests for controlled substances fell”.

Having a law against a substance that is widely accepted in society is quite expensive. As of today, “Californians pay $170 million a year for arrests, prosecution and imprisonment of pot offenders”. Today some people say that California could, “lead the nation out of this depression by legalizing Marijuana” , Tom Ammiano Legalizing marijuana “would bring in roughly $1 billion to the state” each year if marijuana was sold at $50 per ounce, which would convert to “about a buck a joint”. This raises some serious questions however, such as the fact that marijuana will still be illegal by federal law. Thus, citizens of California would still be subject to arrest by federal officials.

California is leading the way to change, but I think that there could be serious issues if the federal government does not back them. In a video posted on YouTube, President Obama stated that he is in favor of the decriminalization of marijuana, but does not believe in the legalization of marijuana. Even with medical use of marijuana approved in some states, this has not stopped federal prosecution of patients and the doctors prescribing it. At a press conference held on February 23, 2009, Assemblyman Tom Ammiano announced the start of his marijuana legalization, Assembly Bill 390. If California passed the bill, it would “remove all penalties under California law for the cultivation, transportation, sale, purchase, possession, and use of marijuana, natural THC and paraphernalia by persons over the age of 21” .

There has been little evidence that marijuana causes deaths yet it is a drug that is deemed illegal in the United States. While tobacco and alcohol are the leading substances attributed to drug related deaths, marijuana is not tied to any causes of death to date. Two large studies have been done by a large health maintenance organization in California in which they surveyed 110,627 people. Their results showed that health of individuals who smoke where no different than those who did not over a period of fifteen years. This however does not mean that there will be side effects of marijuana if the drug becomes legalized. More use only means that long term effects will become more apparent and since “deaths due to chronic diseases resulting from substance misuse generally result from the use of that substance (for example, tobacco and alcohol) over a long time”, it is extremely likely that there will be more side effects found. People who smoke marijuana generally smoke one stick per day whereas tobacco smokers go through 20 sticks a day. This is why there is so little data on the issue of deaths related to marijuana, but this is bound to increase with a legalization of the drug.

VII. CONCLUSION

Though legalization of marijuana has its pros and cons, in relation to The Wire, I see no possibility of the legalization of any of the drugs depicted in the show. Drugs such as cocaine and heroin have such a high mortality rate and in combination with the social fears of the citizens of the U.S., there is no way these drugs could be permitted legally on the streets of America. As the trend in our drug history suggests, if a large portion of society deems a drug useful or acceptable then it is legal, even if it causes the majority of deaths due to drugs; such as tobacco and alcohol do. However if a drug is feared by most of society and has no medicinal purpose it is likely to be deemed illegal. Society’s ideology toward what is right and wrong is the driving factor behind legal and illegal drugs. When you look at The Wire, it is clear that the people on the drug side are those who are against the norms of society and see nothing wrong with what they are doing as it is a way of life. As a society we have created this drug war ourselves by trying to establish what is right and what is wrong. So long as there are rules in guidelines in a society there will always be crime. And so long as there are laws preventing the sale of certain drugs there will always be a drug war.

Sources:

I. INTRODUCTION:

[1] http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1719872,00.html

[2] http://www.newspeakdictionary.com/ct-prohibition.htm

[3] http://www.newspeakdictionary.com/ct-prohibition.html

II. THE HISTORY OF THE WAR ON DRUGS:

The chronology is synthesized from the following sources:

http://uk.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idUKTRE5210VC20090302?sp=true

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/drugs/cron/

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=9252490

http://www.newspeakdictionary.com/ct-prohibition.html

http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1719872,00.html

III. THE SELLERS

[1] Orianna Zill and Lowell Bergmann, “Do the Math: Why the Illegal Drug Business Is Thriving”, PBS Frontline Special Report, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/drugs/special/math.html

[2] Ken Dermota, “Snow Business: Drugs and the Spirit of Capitalism”, World Policy Journal vol 16, no 4 (Winter 1999), 5.

[3] Renselaer Lee, “The Economics of Cocaine Capitalism”, Cosmos Journal, 1993. http://www.cosmos-club.org/web/journals/1996/lee.html

[4] Sibylla Brodzinsky, “Coca Cycle: From Leaf to Market”, MSNBC, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/3071728/

[5] Matthew Brzezinski, “Re-engineering the Drug Business”, The New York Times, June 23, 2002.

[6] Zill and Bergmann

[7] Brzezinski

[8] Edward Burns, “Gang- and Drug-Related Homicide: Baltimore’s Successful Enforcement Strategy”, Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) Bulletin, http://www.ncjrs.gov/html/bja/gang/pfv.html

[9] ibid.

[10] Robert MacCoun and Peter Reuter, Drug War Heresies (Cambridge University Press, 2001), 121-122.

[11] Edward Ericsson Jr., “Shadow Players”, Baltimore City Paper, January 28, 2009. http://www.citypaper.com/news/ story.asp?id=17425

[12] ibid.

[13] Nathan Englander, “Exclusive Interview with David Simon”, The Times (London), September 12, 2008. http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/books/article4739380.ece

IV. THE BUYERS

[1] United States Government, Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), “What America’s Users Spend on Illegal Drugs”, December 2001, http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/publications/pdf/american_ users_spend_2002.pdf

[2] Renselaer Lee, “The Economics of Cocaine Capitalism”, Cosmos Journal, 1993. http://www.cosmos-club.org/web/journals/1996/lee.html

[3] All the previous statistics and tables come from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, “Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings”, 2008. http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k7nsduh/2k7Results.cfm

[4] “Pharmacology: Cocaine”, PBS Frontline Special Report, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/drugs/buyers/pharmacology/cocaine.html

[5] National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Cocaine Abuse and Addiction”, http://www.drugabuse.gov/ResearchReports/Cocaine/cocaine2.html#crack

[6] “Pharmacology: Cocaine”, PBS Frontline Special Report, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/drugs/buyers/pharmacology/heroin.html

[7] Sharon Begley, “How It All Starts Inside Your Brain”, Newsweek, February 12, 2001.

[8] “What is Addiction, and How Can We Treat It?” PBS Frontline Special Report, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/drugs/buyers/treatment.html

V. THE ENFORCERS

The official website of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/index.htm

The Controlled Substances Act on the DEA website: http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/pubs/csa.html

PBS Frontline Special Report: “Drug Wars”, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/drugs/