Why did Robert Gibbs decide to step down as Obama’s press secretary? (For that matter, why was Bill Daley hired as chief of staff?) In his public statement Gibbs cited personal reasons, noting his desire “to occasionally drive his young son to school.” Others observed that, as former Bush aide Ari Fleischer put it, serving as press secretary is “the ultimate burnout job.” It is also no secret that Gibbs, like previous White House staffers, is hoping to capitalize financially on his White House experience. Finally, rumors swirling today suggest that incoming chief of staff Bill Daley forced Gibbs out – a charge Gibbs denies.

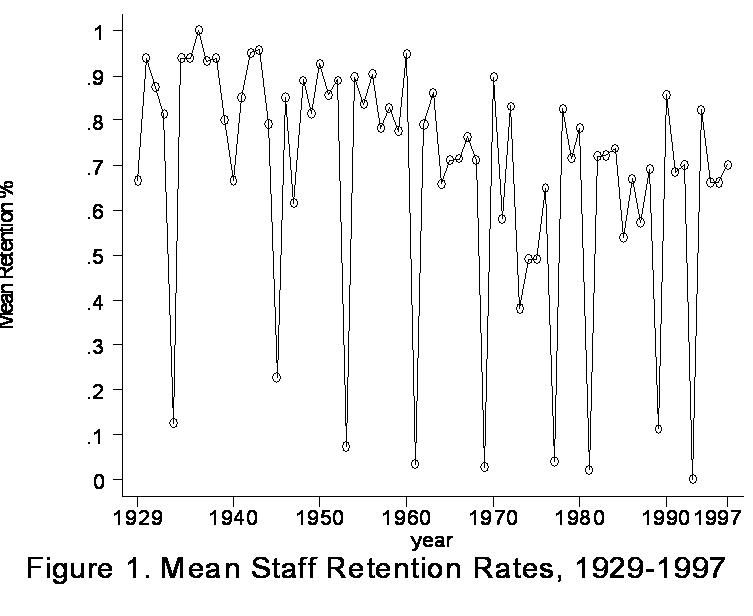

I have no doubt that some combination of these factors contributed in part to Gibbs’ decision to step down. But these explanations ignore a more fundamental reason for Gibb’s resignation: Obama’s senior staff is undergoing the restructuring that most presidential staffs undergo after a president’s second year in office, as they begin transitioning from governing to campaigning. Note that in addition to Gibbs, Obama in recent weeks has replaced or will replace many of his senior level advisers, including his interim chief of staff Peter Rouse, chief aide David Axelrod and senior economic adviser Larry Summers. Meanwhile, former campaign manager David Plouffe will come on board as a White House aide. This turnover is hardly unprecedented – in two articles jointly authored with Katie Dunn Tenpas, I examined staff retention rates among presidential advisers, including both senior White House aides and cabinet secretaries, during the period 1929-1997. As the following table indicates, we found that staff retention rates began dropping beginning approximately in the early 1970’s. (The lowest levels indicate changes in presidential administrations when, as you might expect, almost no aides are retained.)

What explains this drop in retention rates after 1970? We argued that it reflects a change in the way presidential campaigns are run. As we wrote in our 2001 article, “Prior to the campaign finance and delegate selection reforms of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, the traditional party structure–the loose federation of party leaders at the national, state and local levels–provided most of a president’s campaign expertise. The national party organization charted campaign strategy, solicited donations and coordinated the overall reelection effort in response to presidential direction.” This is no longer the case. A series of reforms beginning after the 1968 election, including changes in campaign finance, the growing use of primaries, and new norms of media coverage, created the candidate-centered presidential selection system familiar to us today.

Why should this development adversely affect staff retention rates? We write, “In the parties’ stead, the president’s personal staff has assumed campaign dominance, its members taking major responsibility for providing expertise pertaining to voter mobilization, campaign strategy, spending, policy and media relations. The growing prominence of presidential candidates’ (including incumbent presidents’) personal staffs as purveyors of campaign expertise” has led to increased staff turnover during the post-reform period.

The reason is that, as I have noted in previous posts, governing and campaigning in the post-electoral reform era are, to a certain extent, relatively distinct processes. As a consequence the expertise a president requires from his staff to govern is not always the same skill set he needs for campaigning. Moreover, federal law prohibits White House aides from engaging in purely campaign-related activities while operating on the government payroll. This means, for example, that White House aides must use separate email accounts and communication devices when performing campaign functions as opposed to governing-related tasks. As a result, it is often easier simply to move a senior aide from the West Wing to the campaign staff so that they can focus exclusively on the reelection campaign, which is evidently what will happen with Axelrod.

The bottom line is that the recent turnover among Obama’s senior-level staff is driven in part by systemic factors that affect all White Houses in the post-reform, primary-dominated electoral era. As evidence, note that the mean retention rate for the electoral pre-reform, pre-1971 41-year period is 74% (n=1,284), a statistically significant different average than the post-reform (1972-1997) mean of 59% (n=2,431). As the following table indicates, these aggregate figures reflect statistically significant differences in retention rates across specific years of a presidential term as well.

| Year After Election (Includes All Presidential Terms) | Pre-Reform Retention Rate | Post-Reform Retention Rate |

| First | .42 | .28 |

| Second | .86 | .75 |

| Third | .82 | .64 |

| Fourth | .83 | .71 |

It is not surprising, of course, that retention rates are lowest in the first year of a presidential term, coming off the election campaign. Obviously there will be almost complete turnover if a new president is elected. But even reelected presidents often reshuffle their senior staff at the start of the first year of a second term. Note, however, that consistent with our argument the next lowest rate of retention in the post-reform period occurs in the third year of a presidential term – precisely where we are at in Obama’s presidency. This is not the case, however, in the pre-reform period – retention rates in that era do not vary across years 2-4 of a president’s term.

The bottom line? The modern White House staff moves to a somewhat predictable rhythm, one dictated by a president’s administrative needs. When a president moves from governing to campaign mode, as Obama is now doing, the expertise he seeks from his senior aides changes as well. This invariably produces higher level of staff turnover. News accounts often portray these changes in terms of individual factors, such as staff burnout, personality clashes, the aide’s perceived ineffectiveness or an internal power struggle (Daley forces Gibbs Out!) While not totally discounting these factors, the primary cause for the staff overhaul that we see in the Obama presidency now is systemic, not individual. Simply put, Obama is running for reelection and he is reshaping his White House accordingly.

Addendum: For those interested in reading the original study to which this post refers, including methods and data, see Matthew J. Dickinson and Kathryn Tenpas “Explaining Increasing Turnover Rates Among Presidential Advisors, 1929-1997,” Journal of Politics, Vol. 64, No. 2, May 2002. If I get the chance, I’ll update the retention data through 2010.