With recent polling suggesting a slight hardening of opinion against demonstrators in Ferguson, we take our WayBack machine to September 1966, as President Lyndon Johnson struggles to balance pressure from activists advocating stronger leadership on civil rights against a growing backlash among moderate voters triggered in part by a series of race-related riots in urban areas. Heading into the fall midterms, Democrats running for office grew increasingly concerned that Johnson’s handling of civil rights was going to be a drag on the party’s fortunes.

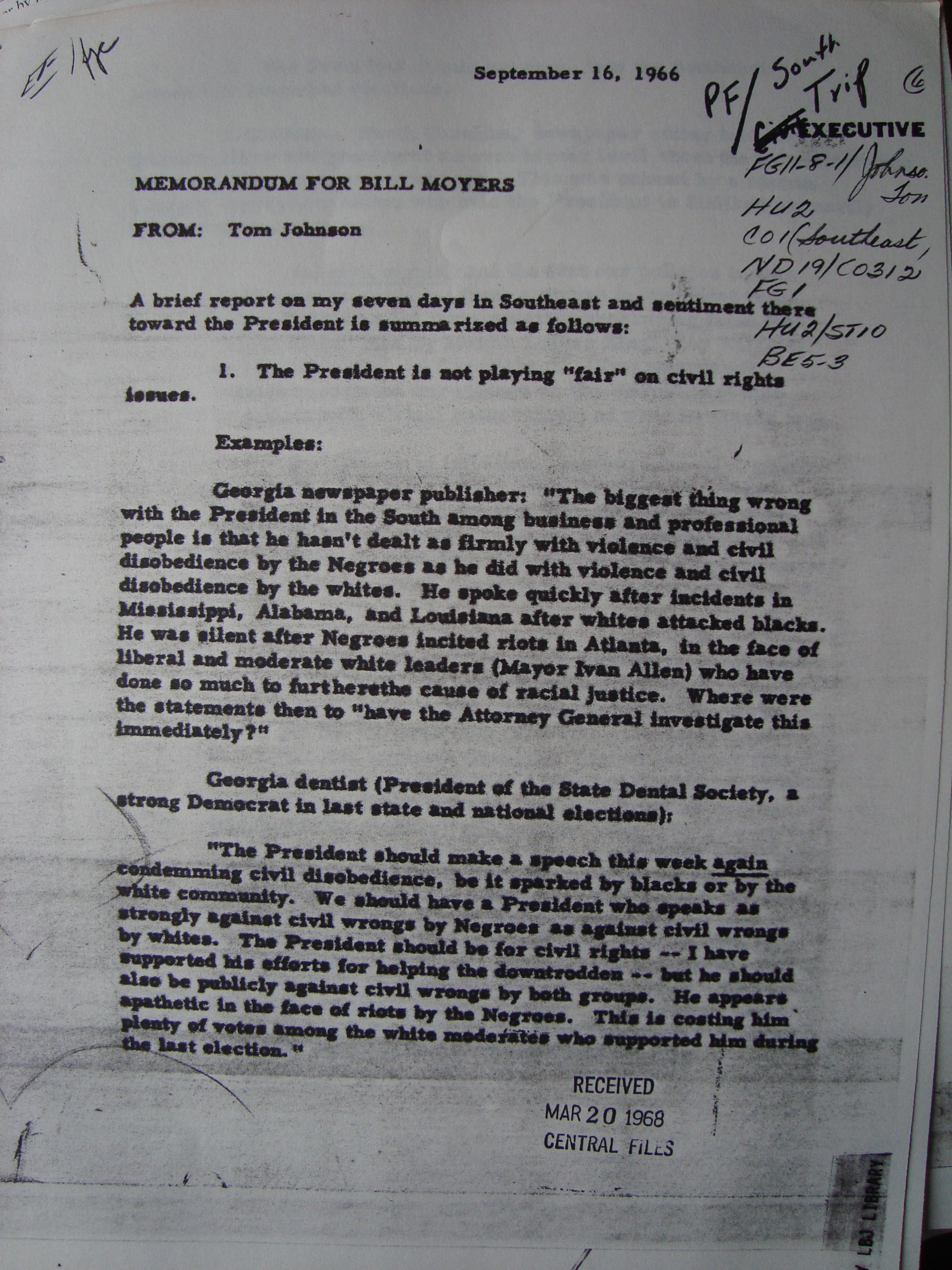

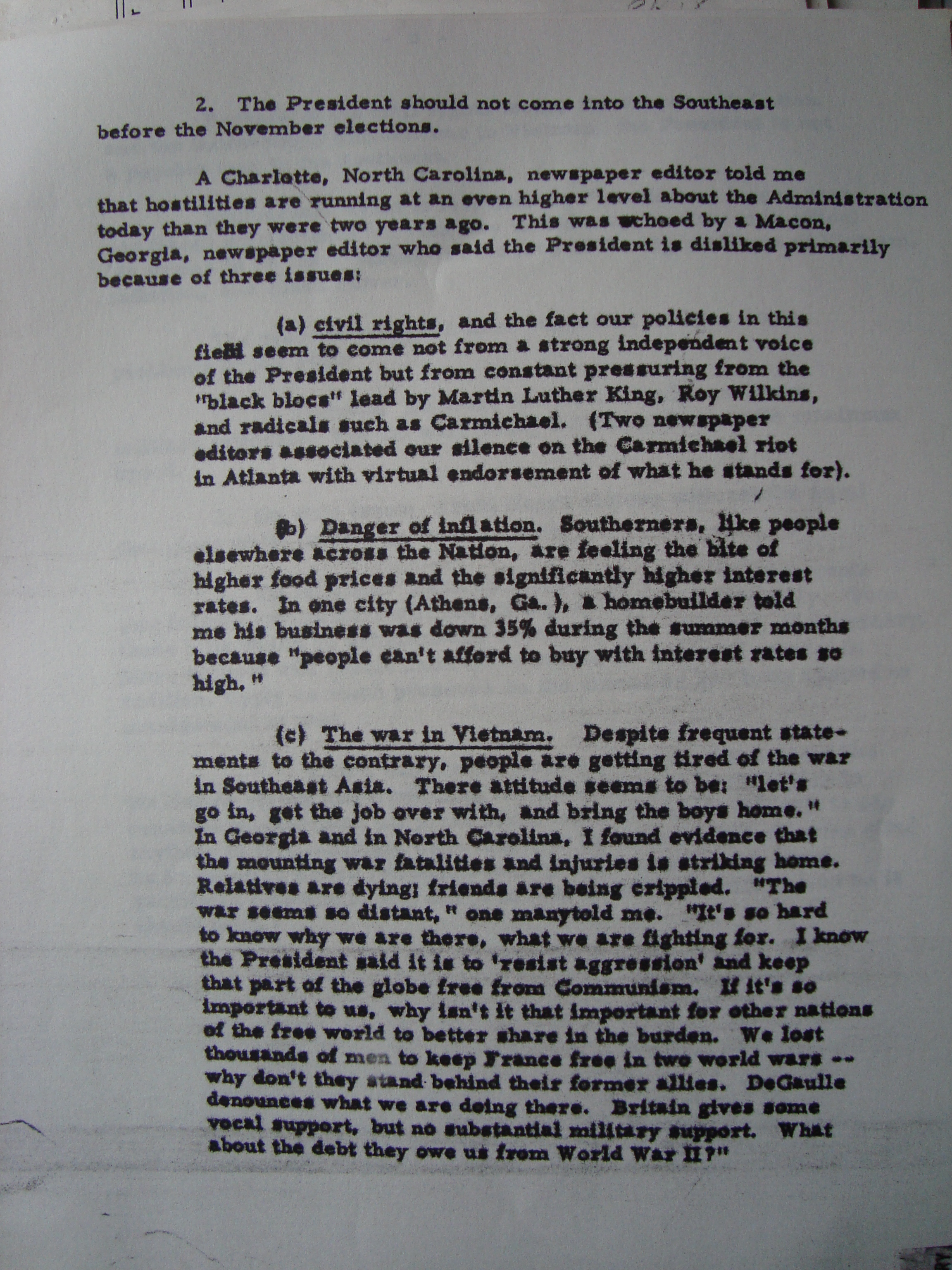

On September 6, 1966 several thousand people rioted in the Summerhill neighborhood in Atlanta, Georgia after Atlanta police shot a black male suspected of being a car thief. White House Fellow Tom Johnson spent a week in the Southeast gauging political sentiments among opinion leaders in that period, and filed the following report with LBJ’s senior White House aide Bill Moyers. Johnson drew two important conclusions from his meetings with opinion leaders during his trip: First, they felt the “President is not playing ‘fair’ on civil rights issues” and second, “The President should not come into the Southeast before the November elections.” Here are the first two pages of the three-page memo to Moyers:

What, according to these opinion leaders, should LBJ do to change the political calculus? “Treat Negro rioters with rebuke equal that given white troublemakers in past.”

Note that the “Carmichael riot” cited in the second page of the memo refers to the Summerhill area riot in Atlanta. Stokely Carmichael, a leader of SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), had been accused of inciting the riot in the immediate aftermath of the police shooting. (At this time SNCC had spearheaded a voting rights drive in Atlanta with the goal of electing a black to the Georgia legislature, but there was disagreement with SNCC regarding what role whites should play in the movement. That presaged a split in the civil rights movement regarding the most effective tactics for furthering the movement’s goals.)

As Johnson’s memo makes clear, not all of the displeasure with LBJ was due to civil rights; Johnson’s memo also notes the first signs of growing unease with the U.S. escalating military presence in Vietnam, and rising concern over inflation. All three issues proved increasingly intractable, and in combination helped fuel the end of the Democrat’s New Deal coalition and the rise of the “Republican majority”. In the 1966 midterm elections, Republicans gained 47 seats in the House, and three in the Senate, although Democrats retained majorities in both chambers. It was a harbinger of things to come. With the exception of Carter’s four years as president, Republicans – bolstered by support from an increasingly Republican south together with white, middle- and working-class Northerners (the so-called Reagan Democrats), would hold the Presidency for the next two decades, and control the Senate too from 1981-87. Despite losing popular support in presidential elections, however, Democrats were able to hold on their House majority throughout this period in part due to the increasing importance of incumbency which helped shelter party members from national currents.

It is far too early to draw firm conclusions regarding the implications, if any, of the Michael Brown shooting and subsequent Ferguson demonstrations on national politics. But as the Johnson memo to Moyers reminds us, and as President Obama knows all too well, the effort to balance protection for civil rights with concern for law and order is an exceedingly difficult task – one for which presidents are unlikely to win any political rewards no matter what their stance.