So little time, so much to blog about. Today’s topics: deadlock in DC, the Perils of Paul in Iowa, and tonight’s debate.

To begin, as I predicted in this earlier post, the Obama administration has backed away from its veto threat in response to changes Congress made to the detainee provisions in the 2012 military authorization bill. Given the already tepid nature of that threat in the administration’s Statement of Policy (SAP), I didn’t think it would take much to persuade Obama to take the veto threat off the table. As you might imagine, party purists on the Left are again voicing their displeasure with the President’s willingness to compromise, and human rights and civil libertarian groups continue to argue the bill cedes too much power to the military. But although the concessions the congressional conference committee made in response to the administration’s objections may not have appeased the Left, they were evidently enough to provide political cover to Obama, and he is going to sign this bill. This is another illustration of something that I refer to often on this blog, but which – surprisingly – is not accepted by all political scientists: that presidential power is really nothing more than persuasion, and that in practice, persuasion takes place through bargaining. The negotiations I’ve described here regarding the military authorization bill are the latest illustration of this fact. Purists, in contrast, view the exercise of presidential power as part of a zero-sum game, where the president either wins by getting everything he wants, or he loses. But that’s not how it works in a system of shared powers. To get anything, presidents need to be prepared to give something up.

Meanwhile, another congressional donnybrook is brewing. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid is now threatening to hold up the Senate vote on an omnibus appropriations bill until he gets Republican agreement to pass an extension of the payroll tax cut due to expire at the end of the year. House Republicans are supporting their own version of a payroll tax cut extension that includes provisions expediting approval of the Keystone pipeline project. So far, the Republican bill is a non-starter with Senate Democrats who are hoping to leverage the threat of a government shutdown to force Republican concessions. In response, House Republicans have gone ahead an introduced their own omnibus spending bill. Their hope is to pass the bill by Friday, thus putting the screws on Reid instead, since Senate Democrats will be forced to either accede to Republican wishes or accept responsibility for failing to pass the spending bill and risking another government shutdown.

This latest round of legislative brinkmanship is sure to bring out the handwringers among the chattering class (and among academics too!) who will cite it as still another example of how our political system is broken. As with the debt default crisis, however, I think this instead is the logical result of having two evenly matched, ideologically cohesive parties, each controlling one house of Congress. As long as both sides see it is in their mutual interest to compromise, they will do so, but not before driving Congress to the legislative precipice in order to wring out every last feasible concession. In this instance, neither Republicans nor Democrats see their brand name benefit by opposing a payroll tax cut, and so they will reach agreement on doing so. Similarly, there’s not much payoff in shutting down the government, so I expect either some compromise on the omnibus spending bill, probably by decoupling it from consideration of the payroll tax extension, or a short-term spending extension while debate continues. Obama, at least publicly, seems to want nothing to do with this confrontation, and who can blame him? He received little credit for negotiating the debt default compromise.

It’s a messy way to legislate, to be sure. But we should get used to it because, barring a return to unified government, it’s here to stay.

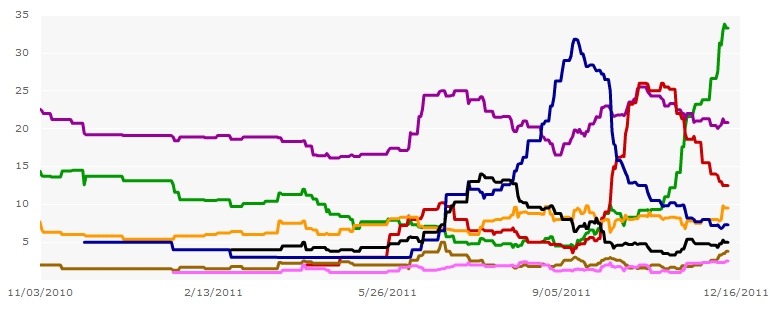

Turning to electoral politics, what are we to make of this Rasmussen automated poll of likely caucus voters in Iowa, which was in the field on Tuesday? (Rasmussen surveyed 750 likely caucus voters. The margin of sampling error is +/- 4 percentage points with a 95% level of confidence)

|

2012 Iowa Republican Caucus |

|||||

| 12/13/2011 | 11/15/2011 | 10/19/2011 | 8/31/2011 | 8/4/2011 | |

| Mitt Romney | 23% | 19% | 21% | 17% | 21% |

| Newt Gingrich | 20% | 32% | 9% | 2% | 5% |

| Ron Paul | 18% | 10% | 10% | 14% | 16% |

| Jon Huntsman | 5% | 2% | 2% | 3% | 2% |

| Herman Cain | Withdrew | 13% | 28% | 4% | 4% |

| Rick Perry | 10% | 6% | 7% | 29% | 12% |

| Michele Bachmann | 9% | 6% | 8% | 18% | 22% |

| Rick Santorum | 6% | 5% | 4% | 4% | Not Polled |

| Some other candidate | 2% | 1% | 4% | 0% | 7% |

| Not sure | 8% | 6% | 8% | 10% | 0% |

Romney, who has been fading in most recent Iowa polls, is ahead here, albeit with a lead that is within the poll’s margin of error. Rasmussen does not provide crosstabs to nonsubscribers, so I can’t check the poll’s internals to gauge what lies behind the results. But a quick read of the topline results suggests that the real story is not that Romney is gaining in Iowa – it’s that some of Gingrich’s support has moved to Paul. More generally, we see a tightening of the race in Iowa, almost certainly reflecting the media blitz targeting Gingrich issued by the Romney, Perry and Bachmann camps. Note that all three candidates have registered small gains since the last Rasmussen poll.

In a video piece we have up at the Middlebury website, my colleague Bert Johnson argues that what pundits perceive as “momentum” coming out of Iowa and New Hampshire is really a function of the various factions solving a coordination problem; in effect, they use these early contests to decide which candidate to coalesce behind. So, if there are two factions in Iowa – say, social conservatives and fiscal moderates – each group has to decide which candidate to support, or risk dissipating their influence. To put this another way the reason we seem to think that a candidate gains momentum coming out of Iowa (or New Hampshire) is really a function of the winnowing process that eliminates second-tier candidates. Their support has to go somewhere. With only about 20 days to go before the Iowa caucuses, however, potential voters seem in no hurry to solve their coordination problem, to use Bert’s term. This is particularly true among social conservatives, who seem to have split their support among Gingrich, Perry, Santorum and Bachmann. Newt has to hope he can get those voters to coalesce behind him. Paul, meanwhile, draws his strongest support among independents, weak Democrats, and young voters. It’s not clear whether he has hit his ceiling or not.

If the race is tightening in Iowa, it makes tonight’s Sioux City debate all the more crucial (and yes, I’ll be live blogging!) The key question will be whether Newt now goes on the attack against Paul and Romney, and whether Perry, Santorum and Bachmann can turn in a second straight strong performance and move into the top four to avoid getting culled from the field.

The debate is at 9 on Fox. I’ll be on a bit earlier to set the table. It is potentially the most significant debate of the campaign season to date so I hope those of you who aren’t studying for an exam (you know who you are) can join me online.