Since I am as guilty as anyone for triggering the Hillary for President mini-boomlet with this Salon post, I should point out that the Salon version left out the opening line that was included in my original version at the Presidential Power site: “She won’t run, of course.” Clinton confirmed my assertion in a recent informal interview on CNN in which she put the chances of her running for the presidency at “less than zero”. Clinton was reacting in part to Vice President Richard Cheney’s widely reported comment that she was a “formidable individual” who was “probably the most competent person they’ve got in their — in their cabinet.”

Clinton’s latest statement is not the first time she’s denied any interest in running against Obama. Every time the story begins to fade, however, another news item surfaces to reignite discussion of a Clinton candidacy. The latest triggering event, as highlighted in this Politico story, is a recent Bloomberg news poll that received heavy media play for its finding that 34% of respondents thought the country would be better off if Hillary Clinton had been elected president. (The poll was in the field Sept. 9-12, and has a margin of error of +/- 3%). That is an increase of 9% from when this question was asked by Bloomberg in 2010. Interestingly, even though majorities of both groups view her unfavorably, Republicans and Tea Party supporters were more likely to say the country would be better off under Clinton than were Democrats; most Democrats believe things would be no different under a Clinton presidency than it has been under Obama.

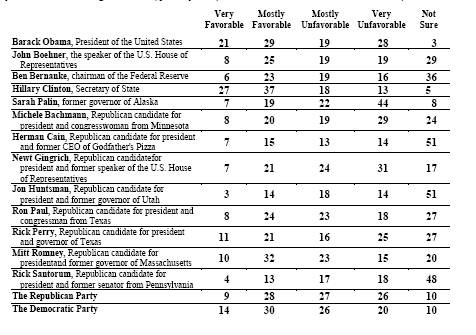

That same poll found that she is easily the most popular figure among a list of prominent political figures that includes all the leading Republican candidates for president as well as President Obama. As the following table shows, 64% view her “very” or “mostly favorably”, putting her comfortably ahead of President Obama, the second most favorably viewed person and far ahead of any Republican.

What most of the news stories downplayed, however, is that although 34% of those surveyed said that things would be better if Clinton had won, 47% said things would be about the same. (Another 13% said things would be worse). Moreover, among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, 67% said Obama is the best Democratic candidate in 2012, while only 30% want another candidate. (Note that Clinton’s name was not listed as an option as an alternative candidate.)

What most of the news stories downplayed, however, is that although 34% of those surveyed said that things would be better if Clinton had won, 47% said things would be about the same. (Another 13% said things would be worse). Moreover, among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, 67% said Obama is the best Democratic candidate in 2012, while only 30% want another candidate. (Note that Clinton’s name was not listed as an option as an alternative candidate.)

This survey reinforces a point I have made before: that (and contrary to Nate Silver’s assertion) Clinton would likely run more strongly than Obama in the general election but would have a very difficult time beating him for the party’s nomination. Given this, I have no doubt that her supporters will continue to promote her candidacy, and that these types of triggering events, whether polling data or pundits’ comments, will continue to keep this story in the news. And, in fairness to those who push this story, in any “normal” election cycle, as I’ve discussed here, Obama would be facing a primary challenge.

The fact that Clinton won’t challenge him, however, reminds me that perhaps Obama’s single best political move to date was nominating her to be his Secretary of State. In November, 2008, I wrote a blog post advising Obama not to make this offer to Clinton, and advising her not to take the position if offered. My advice was correct for Clinton – but wrong for Obama. In fact, given his current political vulnerability, appointing Clinton as Secretary of State now seems like a stroke of pure genius. If there is one factor that makes it difficult for her to enter the race, it’s that she’s a visible member of his administration – probably the most visible. Given her public status, severing ties at this point in order to challenge Obama would, I think, pose a formidable psychological hurdle, never mind the political ramifications that many of you have cited in response to my previous posts on this topic. Consider, however, if Clinton had followed my advice in 2008, and remained in the Senate. From there it would have been much easier to act as a “shadow” president, and to position herself to challenge for the party’s nomination should Obama become vulnerable, as he has.

As I said in my first post on this subject, however, that won’t happen. Obama will be the Democratic standard-bearer and Clinton will likely serve out her term and step down no matter what the 2012 outcome. Supporters will undoubtedly then urge her to run in 2016. In the CNN interview, she didn’t quite close the door to a return to politics. Whether she wants to put herself through that grueling process again, at that point in her life, remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, her supporters may find some solace (or not) in this concession speech from the last Democrat to challenge his party’s President – it is worth listening to the themes he cites: