Who is winning the public debate on how to end the debt impasse? According to a story by Jennifer Epstein at Politico headlined “Obama Winning Debt Spin War”: “President Barack Obama is winning the battle for public opinion in the negotiations to raise the debt ceiling, with the overwhelming majority disapproving of the way Republicans are handling it – even most GOP voters, according to a new poll on Monday.”

Epstein’s story is based on a CBS survey released today. If Epstein is right it suggests that Obama’s recent media blitz, including two press conferences within a week, are having a favorable impact on public opinion. However, if you look at the actual CBS poll cited by the story, the survey results aren’t quite as favorable to Obama as the Politico headline suggests. (The poll was in the field July 15-17, and has a margin of error of +/- 4% – remember that margin is higher for subgroups).

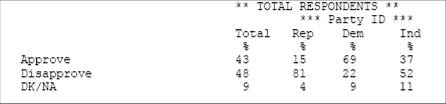

To begin, while it is true that Obama fares better than both congressional Democrats and especially Republicans in the poll, it is still the case that a plurality of respondents disapprove of Obama’s handling of the debt ceiling negotiations.

Handling of Debt Ceiling Negotiations

| Approve | Disapprove | |

| President Obama | 43% | 48% |

| Democrats in Congress | 31% | 58% |

| Republicans in Congress | 21% | 71% |

Still, he might take some comfort in knowing that more people approve of his handling of the debt negotiations than they do the Republicans’. However, this gap seems less impressive when one remembers that presidents are generally always rated more highly than Congress. Right now the RealClear politics composite approval/disapproval rating of Congress stands at 19.2/73.4, while Obama’s approval/disapproval is at 46.3/47.3. In short, the response to this particular survey question regarding the handling of the debt crisis aligns with attitudes toward Obama and Congress more generally. This makes it difficult to tell just how much of the overall ratings of both institutions are influencing the response to this specific question.

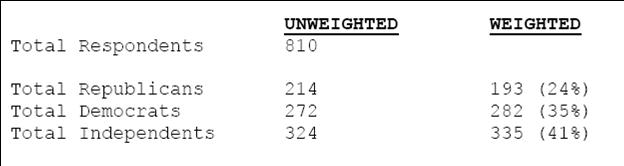

Note as well that CBS has weighted the original sample in a way that slightly increases the number of Democrats responses in the final tally; they increase by 10 from the actual unweighted sample, while Republicans lose 21 respondents.

Without knowing the demographics of the survey I can’t cast any judgment on the particular choice to weight this way – it could very well be necessary to increase the accuracy of the reported polling results . But it does make a potential difference in how we judge the results because there is a sharp partisan skew in the responses, with most Democrats (69%) approving of Obama’s handling of the negotiations, while a strong majority of Republicans (81%) disapprove.

Perhaps most disturbing for Obama, however, is that a majority of independents (52%) disapprove of his handling of the negotiations, with another 11% unsure. Only 37% of independents approve. Independents are, of course, the group that Democrats lost in the 2010 midterm, after Obama had won them in 2008.

So it is unclear if, as Epstein claims, Obama is really winning the public debate regarding the debt limit. But it might not matter anyway. Longtime readers will remember that, when it comes to disputes between the Congress and the President, broad-gauge approval/disapproval numbers tell us very little about the popular dynamics driving the debate from Congress’ perspective. This is in part because members of Congress care less about national opinion, and much more about state or district-level attitudes, particular among core voters (although there is some evidence that national factors are looming larger in recent years). For most Republicans, when 81% of your party and 52% of independents oppose the President’s handling of negotiations, that doesn’t provide much incentive to give ground.

Of more interest than these approval/disapproval surveys, I think, are surveys gauging the public’s attitudes toward specific options for solving the debt crisis. You’ll recall that President Obama, in his press conference a week ago, suggested that most Americans weren’t paying close attention to the details of the various options being debated to end the debt impasse. His view was echoed by his press secretary Jay Carney at the end of Carney’s July 13th press briefing in response to a question about a Gallup poll indicating that a majority of Americans did not want their representative to raise the debt ceiling. Carney responded in a way that suggested Americans might not fully understand the implications of not raising the debt ceiling:

“So I think it’s easy to understand why most Americans don’t have a lot of time to focus on what is a debt ceiling. I mean, honestly, did anybody in this room, before they had to cover issues like this, have any idea what a debt ceiling was? Any understanding of the fact that a vote by Congress to increase our ability to borrow was simply a vote to allow the United States of America to pay the bills that it incurred in the past?

I think every American, or certainly a vast majority of Americans, would accept the principle, if asked, that the United States should pay its bills, just like they’re asked to pay their bills.” on the issue.”

In last Friday’s press conference, however, Obama switched gears to suggest that polls indicated strong support for a balanced approach to solve the debt crisis. “You have 80 percent of the American people who support a balanced approach,” Obama said. “Eighty percent of the American people support an approach that includes revenues and includes cuts. So the notion that somehow the American people aren’t sold is not the problem. The problem is members of Congress are dug in ideologically into various positions because they boxed themselves in with previous statements.”

I’ll put aside for the moment the potential tension between his dismissing polls gauging the public’s knowledge of the policy options on Monday while citing their support of the “balanced approach” as indicated in polls on Friday. The more important issue is: when it comes to addressing the debt crisis, is he right? Do most Americans want a “balanced” approach? And what does that mean, exactly?

I’ll address that in my next post.

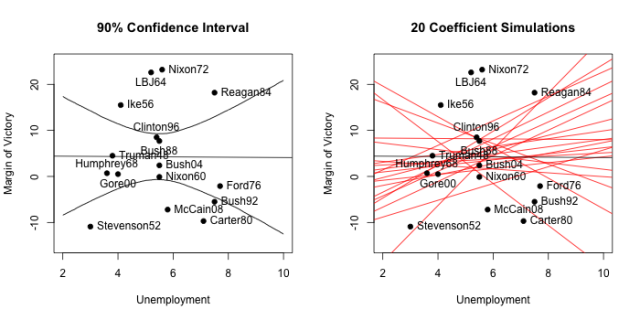

Masket’s conclusion? “The fact is, as the above scatterplot demonstrates, the

Masket’s conclusion? “The fact is, as the above scatterplot demonstrates, the