The post-Arizona shooting speeches by President Obama and Sarah Palin provide a useful window for viewing their strengths and weaknesses as presidential candidates in 2012. Obama’s speech (see here) was largely (and correctly in my view) praised for its content, tone and delivery (despite the sometime raucous audience reception that seemed somewhat inappropriate for the somber occasion). In contrast to the highly inflammatory finger pointing that occurred shortly after the Arizona shooting, Obama pointedly rejected efforts to blame the tragedy on anyone but the shooter. And by focusing on the personal stories of the victims, interspersed with liberal references to Scripture and to enduring political values, his speech transcended partisan divisions and spoke instead to what unites Americans. It was a potent reminder of not just Obama’s rhetorical skills, but also of the latent power of the presidency. In times of tragedy, people are more likely to view this office, and its occupant, as a symbol of national sovereignty as opposed to a political position and figure. This typically produces a rally-round-the president effect and a short-term bump in presidential approval ratings. The President becomes, in effect, the Healer-in-Chief. Recall Ronald Reagan’s national address after the space shuttle Challenger exploded, or George W. Bush’s moving speech at the National Cathedral after 9-11. Obama’s Tucson speech is just the latest manifestation of this phenomenon.

The positive reaction to Obama’s speech led some pundits to suggest that it might prove to be a turning point in his presidency, similar to what happened, they claim, when Bill Clinton gave a similarly powerful speech in April 1995 in the wake of another national tragedy – the Oklahoma City bombing that killed 168 Americans. I don’t disagree that in the aftermath of the Arizona shooting, Obama’s speech will likely produce a short-term spike in his approval ratings; indeed, we are already seeing evidence that this may be occurring. According to Gallup’s three-day rolling tracking poll, Obama’s approval/disapproval rating stands at 51-41 today, up from 48-46 in the Jan. 5-7 average from just before the Jan. 8 shooting, and 48-45 in the three days before his Tucson speech. If I’m reading the data correctly, this marks the highest approval rating for Obama in Gallup’s three-day tracking poll since May, 2010. To be sure, the modest gain is within the poll’s margin of error, so we can’t be certain whether it signifies anything more than statistical fluctuation inherent in survey samples. And there is evidence that Obama was already receiving a modest rise in approval ratings even before the shooting. (I’ll address why this might have happened in a separate post.)

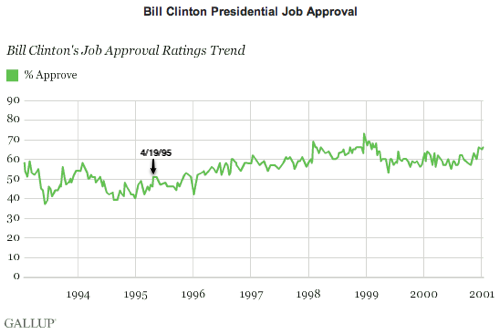

Whether or not Obama is benefitting from a post-speech bump, the argument that his presidency may experience a reprise of Clinton’s Oklahoma City “turning point” misreads the impact of that event on Clinton’s presidency. Although the Oklahoma speech did provide a brief uptake in Clinton’s approval ratings, that bump soon dissipated as the following chart indicates.

Thereafter, however, Clinton’s approval ratings began a gradual improvement that persisted, more or less, to the end of his presidency. What explained this turnabout? Rather than a single speech, what salvaged Clinton’s presidency was a steady increase in job growth, combined with a political strategy that capitalized on the public backlash to Republican overreach. But it took the Republican takeover of Congress in 1994 to convince Clinton to tack to the Right by adopting Republican policies in areas such as law enforcement and welfare reform while using his veto to block more extreme Republican policies. Over time, that strategy, against a backdrop of steady job growth, did much more to rehabilitate Clinton’s presidency than did the Oklahoma City speech.

Clearly this lesson has not been lost on Obama – every move he has made since the November shellacking has essentially reprised Clinton’s strategy. In addition to repudiating his own party and extending the Bush tax cuts for all income brackets, he has appointed centrists from Clinton’s presidency to key advising posts, and has made a number of campaign stops – most recently in upstate New York – designed to signal his post-election focus on jobs, jobs and jobs. Whether this will lead to his reelection hinges primarily on whether voters perceive that the economy – particularly job growth – is moving in the right direction. By 2012, the impact of the Tucson speech, if any, will have long dissipated. This was an effective speech, but it was no turning point.

A few days after the Arizona shooting Sarah Palin gave her own response in a shorter speech posted on her website. Poised against the backdrop of the American flag, Palin also sought to use the tragedy to remind Americans of core values – free speech, American exceptionalism and other “foundational freedoms”, and to transcend the bitter partisanship that characterized the initial response to the tragedy. In its own way, her speech was quite statesmanlike – even presidential. But the media response – particularly its effort to dissect her use of the phrase “blood libel” – is a reminder of just how polarizing she remains. The media reaction was undoubtedly partly provoked by Palin’s pointed critique in her speech of the post-shooting media feeding frenzy that initially focused on whether Palin’s rhetoric had “caused” the shooting – a charge that Palin understandably rejects. But the reaction also reminds us of the different institutional vantage points occupied by Obama and Palin. Obama’s use of the presidency to eulogize the Arizona shooting victims and to derive important moral lessons was viewed by most as perfectly appropriate for the occasion. In the aftermath of a national tragedy, we expect the President to play a healing and unifying role. Lacking an equivalent vantage point, however, Palin’s words were interpreted differently, as the latest volley in a partisan skirmish in which she was a central combatant. Her remarks were viewed as self-serving, whereas Obama’s were not.

The two speeches, then, remind us of the limits faced by both candidates as they gear up for the 2012 election. Obama’s Tucson speech represents not a turning point, but instead a momentary opportunity to rise above partisan politics. To his credit, he capitalized on this moment. But it is an opportunity that is unlikely to be replicated in the months ahead, as he begins to campaign in earnest on issues that will prove more often than not quite divisive. If his approval ratings rise, it will be because unemployment drops, and because increasingly voters will evaluate him not in isolation, but in a head-to-head comparison with potential Republican rivals. Palin, on the other hand, had the more difficult task in her post-shooting speech. She also tried to achieve the moral high ground by citing overarching American values, but to do so meant also criticizing those who blamed her, however recklessly, for inciting the Arizona murders. That she failed to accomplish this says less about her speech than it does about her lack of an equivalent vantage point from which to transcend – even momentarily – the politics of polarization that has become such a central part of her public persona.

Thanks for the interesting post. Obviously, President Obama and ex-Mayor/ex-Governor Palin have different positions in American life. But you write, “Her remarks were viewed as self-serving,” and try to explain it away. Sorry. Her remarks were viewed as self-serving and not at the right pitch and tone because they were self-serving and did not achieve the right pitch and tone. Compare what Palin said with Senator John McCain’s comments in The Washington Post.

Marty