The debate during the last several weeks regarding Rahm “Rahmbo” Emanuel’s role in the Obama White House provides an opportunity to revisit a topic that is one of my main research interests, and about which I’ve written extensively in academic journals: what is the most effective way for a president to organize his White House staff? To anticipate my answer below: it’s not by having a chief of staff who serves – as Emanuel apparently does – as a de facto “prime minister” of government.

Note that my criticism of Emanuel’s role differs from that of progressives like Dan Froomkin and Katrina vanden Heuvel, who argue that Emanuel’s brand of “purple centrism … is dangerous to Obama’s presidency”. In part, the progressive critique dates back to the 2006 midterms, where Emanuel, as the Democratic Party’s campaign committee chair, recruited moderate and conservative candidates who won races in normally Republican-leaning districts. Emanuel’s critics argue that Emanuel missed an opportunity to capitalize on the Democratic wave that year by recruiting more progressive Democrats to Congress. Instead, these conservatives are now a roadblock to passing health care. I think this is a dubious claim; as this American Prospect article points out, “only 12 of the 41 Democrats elected in 2006 number among the most conservative 20 percent of all House Democrats in the current Congress — which is to say that they are not dramatically more conservative… .”

Nor do I disagree with Emanuel’s defenders who portray him – not inaccurately – as the White House’s “voice of reason”.’ Instead, my criticism centers on the tension inherent in Emanuel’s expansive role as both chief of staff responsible for coordinating operations within the White House and chief lobbyist on Capitol Hill on behalf of the President’s legislative program. That role is described in some detail by Peter Baker in his New York Times magazine article published last Sunday. In Baker’s words, “Emanuel seems to serve as a virtual prime minister, the most powerful chief of staff since James Baker managed the White House during Ronald Reagan’s first term.” Baker summarizes Emanuel’s role this way: “[Emanuel] meets with Obama at the beginning of each day and again at the end, in between dipping his hands into virtually everything the White House does, from economic policy to national security. In any meeting with the president, he sits to Obama’s left and is typically called on at the end to summarize arguments and present his recommendations. He works the phone and e-mail with energy, staying in touch each day in staccato fashion with a dizzying array of lawmakers, officials, lobbyists, journalists and political operatives.” That is consistent with the description in this article of Emanuel’s role: “According to almost everyone who has ever worked with him, he has an insatiable need to be in the mix, and he is deeply concerned with the news of the day. His office is the White House nerve center. ‘In order to get a final decision, everything needs to go through Rahm’s office,’ said a former administration official … .”

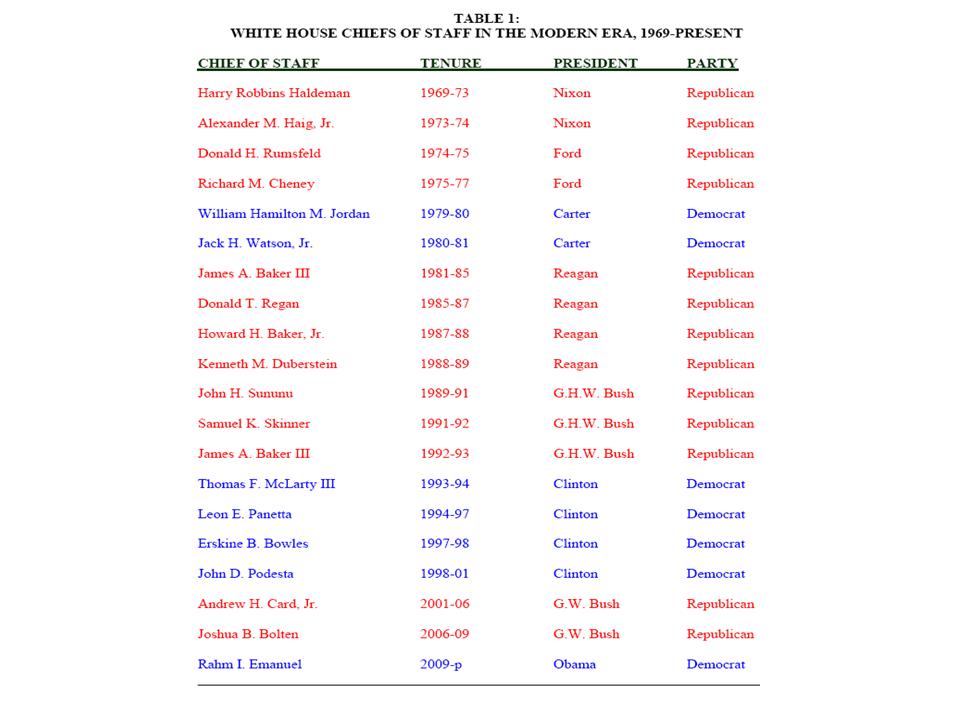

History suggests that chief of staffs like Emanual who serve as both chief political officer and who operate as the White House “nerve center” tend to attract criticism earlier and more extensively. The result is that they become political liabilities much more quickly than do chief of staffs who serve either as chief political officer OR serve primarily as the administration’s traffic cop. As evidence, consider the following table compiled by Andrew Cohen that lists every chief of staff who has served since Nixon’s administration, when the chief of staff role became an institutionalized part of the modern White House staff organization. (Note: it may be easier to view the table by clicking on it to view as a separate document.)

I’m currently putting together more detailed data regarding the time served by each of these chief of staffs, but using the years listed here by Cohen we see that the chiefs’ average tenure is about 2 ½ years. However, this is a bit misleading, since not every chief of staff listed above had the opportunity to serve a full term. If we restrict our analysis to those seven chiefs who, like Emanual, took their post at the start of a presidential term, we see that the average tenure is closer to about 3 years. Note, however, that this average figure obscures clear differences among the tenures of particular chiefs. To understand why these tenures differ, I’ve constructed an admittedly crude table that attempts to place each chief in one of four boxes, depending on whether they served primarily in a political advising role, an administrative coordinating role, or both. Within each box I also list the average number of years each “type” of aide served. Again, this is a rough approximation of their time in office, but I think it illustrates my point.

| Strong Political Role | Weak Political Role | |

| Strong Coordinator | Sununu, Regan, 2 years | Card, Haldeman 4.5 years |

| Weak Coordinator | James Baker, Rumsfeld 3 years | McClarty 1 year |

Emanuel is often compared to James Baker, who, as Peter Baker writes in the Times piece “was also an experienced, savvy operator who took the arrows for his boss. Just as Emanuel is often criticized by the left for steering Obama toward the middle, Baker was considered a moderate who tempered Reagan’s more conservative instincts.” But there is a difference. Baker, particularly early in his term, largely delegated administrative oversight to his deputy Dick Darman. And Baker’s influence within the White House was tempered by the countervailing presences of Ed Meese, Reagan’s chief policy adviser, and Mike Deaver who handled Reagan’s public side.

Admittedly, the data is at best suggestive. There are surely other factors at play that might explain the different tenure rates. Both John Sununu and Mack McClarty, for instance, had little national experience which may partly explain their early departures. On the other hand, Don Regan had already served four years as Treasury secretary before moving to the White House. And it may be that aides who take on as much as Emanuel simply burn out more quickly through sheer physical exhaustion.

Nonetheless, the data is also consistent with my claim that the longest serving chief of staffs are those who either serve as the President’s political lobbyist, or who operate primarily behind the scenes as the White House staff manager, responsible for coordinating the actions of the various White House staff units. In contrast, chiefs of staff who try to exercise both political control and serve as administrative coordinator frequently end up doing neither very well – a recipe for a very short tenure in the White House.

If health care fails to pass, and the Democrats lose control of the House in 2010, the pressure on Obama to revamp his staff will be immense. As a skilled infighter, Emanual will be tough to remove (assuming he wants to retain his position). But I would not be surprised if Obama “promotes” Emanual to political adviser, and turns over administrative control of the White House to someone else.