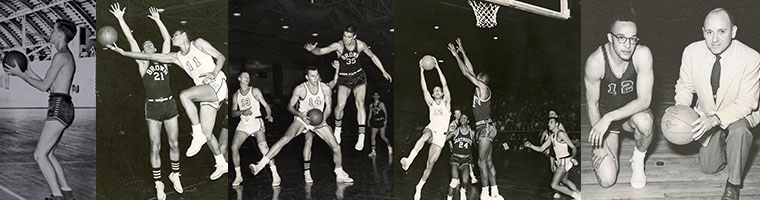

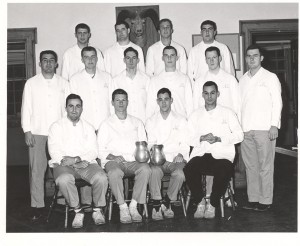

Sykes (bottom row, far right) worked as a waiter in the Gifford Dining Hall with teammates Zip Rausa and Jim Wagner (also pictured).

Charles Sykes ’57 ran track in addition to playing basketball at Middlebury. Off the court he worked as a dishwasher in Gifford, which served as a dining hall at the time. Sykes spent 25 years after graduating overseas, serving first in the military before rising through the ranks of CARE. Sykes still plays tennis and only recently stopped playing basketball after breaking his hand while playing in the Senior Olympics alongside Zip Rausa.

Damon Hatheway: You came to Middlebury after a number of futile years for the basketball program and then after you left they reverted back to being a one-win team in the early 60s. How did you choose Middlebury and why did things change during the 1950s?

CS: I had finished high school in East Baltimore, Dunbar High School, before Brown vs. The Board of Education [had been decided]. My parents thought it would be useful since I graduated in February from high school that I might spend six months at a prep school, which a friend of ours had sent their son to. [So] I spent a year at a little place called Tilton School in New Hampshire. That was my first knowledge of New England. As a result I became acquainted with some of the schools in New England. I did play basketball at Tilton and the coach was from the UNH and he wanted me to go to New Hampshire — he thought I could perhaps play ball there. But one of my friends at Tilton went to Middlebury. He was the year ahead of me, and he invited me to come up to Middlebury during my final year at Tilton, and I went up to meet him and talk to him. I went up and I liked the school, I liked the location, I enjoyed meeting the people there. I had contact with the admissions office and they had looked at my transcript and they were willing to give me admittance to Middlebury. Amongst the other schools of interest were New Hampshire, University of Vermont, and Brown. But I liked Middlebury, and since I knew someone there I thought that would be a good starting point. But by the time I got there the person I knew had left — had transferred somewhere else, so I didn’t really know anyone. But I did like the school. I thought it would be good to go to aschool that was more demanding academically [with] less [of an] emphasis on playing sports, which was true at Middlebury — there was very little pressure.

When I got there I enjoyed the people that I met and made new friends, and so on. My freshman year I flunked ROTC, which I think is a record, which no one else has ever managed to match. But later I graduated as a distinguished military student. So I guess I learned my right foot from my left foot. It was a bit of a struggle at first — the first year at Middlebury — but I settled in and enjoyed it. And basketball was one of the greatest diversions [during] those long winter games and early darkness. And working as a waiter at school and taking courses early in the morning, it was nice to go down to the Field House and throw the ball around.

DH: What kind of coach was Tony Lupien and what impact did he have on the program?

CS: Lupien was a very, very interesting person. I always liked to describe him as the “Dean of Life Sciences” because he was constantly engaged and talking with the team and with individuals on the team. He himself had had a very illustrious life, having graduated from Harvard and been captain of two sports [there]. Then he joined the Boston Red Sox in 1941, I believe, and had a couple of good years with the Red Sox before he went to the Navy. But he was a very interesting person to be around because he had a sense of humor and he had these interesting tales, which he would tell, which usually revolved around sports and stories that are passed on from generation to generation amongst those in the locker room.

He was also sort of a celebrity in New England. Everywhere we visited and had games people would recognize him — there would be shouts “Hi, Tony!” Tony knew all these people in every corner of New England, including northern New York state. Everywhere we went they would great him very warmly and vice versa. These were people who were not often professionals — [it was] the bellman at the Hartford Hotel or a gas station attendant or a locker room attendant. And we always wondered how he knew all these people. We all conjectured as to where he might have met these people and finally one day he told us, as we met a gas station attendant, we asked, “Where did you know him from, Tony?” He said, “Harvard Thirty-Four (’34).

And this would go on over and over and over again. One season we went down to Cambridge to play Harvard in a very low-scoring game. We beat Harvard that evening, and as we were leaving we heard someone say, “Hi, Tony.” And Tony turned around and said, “Hi, Jake.” And we all looked at each other and said, “Harvard, Thirty-Four!” In a way it told a story about Tony. He was very democratic, in the Greek sense of demos — the people — he knew the people and the people knew him. This was part of his character and part of his moniker, this recognition. And it might have reflected the fact that not everyone who went to Harvard, in a way he was saying, was a successful person in the corporate world, or in the government, or making their name in a variety of other fields. I guess that was the underlying message that he was sending to us. Anyway that’s what we drew [from it] — maybe we didn’t reach the right conclusion, but that’s what we thought after knowing him for several years.

DH: You’ve shared one or two already, but what are some of your favorite memories of [Tony]?

CS: There are so many! I think one of the funniest ones [was] he had invited us all to his house and had prepared a great big meal — spaghetti and meatballs. He had been working on the spaghetti and meatballs all day and we were enjoying it, and he was telling us this story. He said, “I like all of you guys, but I’ll tell you one thing: you know I have four daughters, but I would never think of any of you if you walked down the street with your sports bag and your tennis shoes over you shoulder. You wouldn’t be eligible to go out with one of my daughters — I just don’t trust you athletes.” [He said this] with a big smile on his face, of course, afterwards. And we did meet his daughters and they were delightful and very much loved their father and held him in great esteem. As we did.

DH: How was he able to recruit or attract such great players like yourself, Sonny Dennis, Tom Hart? How did he bring that kind of talent to Middlebury?

CS: I don’t know! Maybe [Donald] Rowe or someone was doing some kind of recruiting for him. No one ever approached me about going to Middlebury to play sports. I just went down the gym when the tryouts were taking place! So the question of how Tom Hart and Sonny Dennis, who were really the central figures in the success of the teams in that period, were recruited, I’m not sure. To be honest, I can’t say that I know. I was never recruited — I just went down because I needed a break from studies and work and just went down to the Field House one day and tried out and happened to make the team. The story might be a bit longer for Sonny and Tom, but I’m not sure.

DH: What kind of coach was Tony Lupien on the basketball floor?

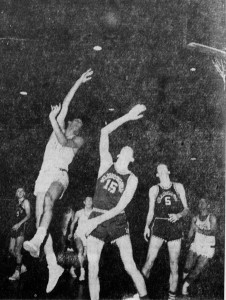

CS: He was serious. First of all, no joking around. He understood that he wasn’t in the Major Leagues. In other words, he kept spirits up by often telling stories. For example, during my freshman year, I remember sometimes there would be about 30 or 40 people in the stands watching the game. And Tony would be in the locker room before the game and he said, “By the way boys, don’t let the crowd scare you when you go out there.” And when we would go out on the court and there wouldn’t be anyone in the stands at all, maybe 30 or 40 people. But it was interesting, in successive years there were more students, more towns people and faculty coming to watch the [basketball] games than the hockey games, which was unusual, because we could never compete with hockey in terms of attendance during [my] first year. But we started a winning streak and you could see the people ducking out of the hockey game and come over and watch the basketball!

DH: What was so special about [Tom Hart and Sony Dennis], and what was it like having two guys who were potentially pro basketball players on such a small campus?

CS: Sonny [competed] all year round — he was also an excellent football player. He was a back in the double wing formation. I ran track with both [Sonny and Tom]. Again they were so outstanding in track and field as well as basketball. Sonny was extremely competitive and he could hold his own probably with anybody we played against. Tom was a spectacular jumper — in track and field he high-jumped and also broad-jumped. He had this remarkable ability to get up above the rim at a time when dunking was discouraged, in fact I think Tony would have pulled anybody out of the game if they had tried to dunk the ball. But Tom was able to set such spectacular statistics in the rebounding game that I think are just incredible.

Unfortunately Tom missed a season in which he and Sonny would have played together again. And unquestionably when they were together it was just magical what they could do in terms of scoring and rebounding and how superior there play was to anyone else. In many ways the record seasons that they assisted at that time were attributable to their being together. Tom had to drop out one year to go to Mitchell College to make up some courses, and so he missed the season. When they were together it was spectacular.

DH: You, Zip Rausa and Carl Scheer were roommates — [what can you tell me about those individuals]?

CS: Carl [Scheer] transferred from Colgate and we did room together [during] my final year — that was a great experience. [Carl] continued his interest in sports and was the General Manager of the Denver Nuggets and now has moved on to Charlotte with the Bobcats. He had established a link with [Michael] Jordan, which has worked out over the years. Carl was a good friend and teammate.

Zip is very special because he was a teammate, classmate and was a roommate! And then one of the special carry-overs from basketball was that about 10 years ago we got together [and played] on the Virginia local team of over-sixties and played together in the Senior Olympics, representing Virginia in the 60 to 65 age group. Unfortunately I broke my hand in one of the games, which ended my playing days, but Zip continues to play, which is amazing. But it was great to have that opportunity to join forces with him again after all those years and enjoy the memories and enjoy the new experiences!

DH: When I spoke to Zip Rausa, he told me to ask you about a great performance that you had against Dartmouth — can you share more about that?

CS: It was my freshman year and we went up to Dartmouth to play Dartmouth and we lost in overtime. It was the first away game I ever played, and it was a great game. I was matched [up] with a guy named Pete Geithner, who’s the father of the former Secretary of the Treasury, [Timothy Geithner]. I later met [Pete] in New Dehli when I was the CARE Director in India in the early 70’s. And I didn’t let him forget that I held him to six points in that game and outscored him! It was a great game — I wish we had won it — but they were awfully good.

DH: Did race play a big role during your playing days at Middlebury?

CS: No it didn’t, it wasn’t a factor.

DH: What moments, games or accolades stand out most from your playing career?

CS: One, which is sort a disappointment for me. We were playing in Springfield [against] AIC, the American International College, and I got my fingers hooked on my rim. I had to get four stitches in between my fingers. For the next four games I had my fingers taped together on my right hand. It was such a disappointment because we lost three of the four games and I always thought that if I had been able to overcome that deficiency it would have made a big difference for the team. We lost some bad games and I felt badly about it.

The Campus called Sykes “the sparkplug” in a win over Norwich. Sykes had 20 points and 17 rebounds in the game.

DH: How about memories that stand out the other way?

CS: [Laughs] I guess against Williams I had a great night my junior year. I think I scored 26 points against Williams and we beat them by 20 points and they were so mad. They were so annoyed at us that when we went down there the next year they took it out on us at Williamstown, they really beat us badly. But it was great that evening [at Middlebury].

And then we played Army once at West Point and I remember that game well, because we were being harassed by the cadets. We were supposed to be steers, they kept saying, “These guys are steers, they don’t know how to play basketball.” Anyway they beat us. But in the subsequent four decades that followed us, one of the organizations that I worked for had conferences at hotels there on the campus of West Point. It was remarkable to see the transformation of the academy in those 40 years. When we went down to play them there were no women, there were very few minorities. In the subsequent years, culminating in the final one when the head of the core was a Vietnamese-American woman, leading the cadets out onto the ground. I thought it was so remarkable that first year when we went there, there were just male white faces in the crowd and a few brown faces, maybe, — and no women at all. And then to see each year successively this metamorphosis in gender and race and creed was remarkable.

DH: You came back to Middlebury last year for the Williams game. What kind of transformation have you seen at Middlebury over the years and how close have you stayed with the basketball program?

CS: [Zip and I] have been following the basketball program, mainly applauding its great success. To be ranked nationally is just incredible for successive years — not just one year, but for three or four in a row and to have players like Ryan Sharry and Nolan [Thompson] and others — they’re just spectacular. So for us, it’s amazing to see Middlebury keeping all its fine tradition of outstanding scholarship and intellectual achievement [while] being matched with this athleticism. It truly is the idealism of the ancient Greeks in terms of intellect and physical achievement.

DH: How were you able to apply what you may have learned while you were playing basketball to your post-Middlebury career.

CS: That’s an interesting question. In 1962 I was in Algeria with a medical team, which was filling in for the French at a hospital in Algiers. The French had left a terrible situation after a 10-year civil war, after a war between France and [Algeria], which was their overseas colony at the time. [Algeria] got [its] independence in ’61 and in ’62 a civil war broke out between two Algerian groups contending for power. We had a medical team of volunteer doctors and nurses manning one of the hospitals there.And my Algerian counterpart asked me if I was interested in working with some young people — young Algerians in the city. One of the things I did [was] start a basketball program for them. Given those long years of war and hostility, those kids really needed some diversion and some outlet to soften all the misery and killing that had taken place over that time. So that was one of things that my experience at Middlebury enabled me to do later, which was more avocational. [Laughs] I think it was good for me too, there’s no question about that, to be able to get out with those kids. And they were happy to have an opportunity to play. Subsequently, when I went to Somalia and other places, I always took balls with me and needles and pumps, because I knew my colleagues out in the field were managing camps and providing assistance and trying to alleviate some of the poverty. I knew that somehow simple sports that didn’t require a lot of equipment were useful and valuable in terms of working with the kids in the refugee camps and villages. They needed this, and they had so little. So those were very valuable carry-overs [from Middlebury].