John Morton, Midd ’68, in the Mekong Delta, 1970

Writing on the Vietnam War

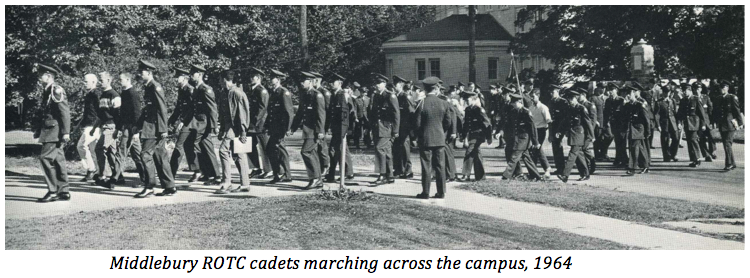

The Vietnam War, in all its dimensions, defined my generation. When I talk or write about Vietnam, I usually begin with, “I didn’t serve in Vietnam, but many of my friends did,” and that’s true. Middlebury College, when I was there, had an Army ROTC program that was required of all male students for a minimum of two years. After that, it was voluntary. Successfully completed, a student graduated from Middlebury with the rank of Second Lieutenant and a three-year military obligation. With the draft looming, it was considered a wise choice to volunteer through ROTC and serve therefor as an officer. Crudely put, as it often was, “would you rather give orders – or take them?” This decision, for Middlebury men my age, sent them to Vietnam. And while it’s true that many college boys found a way to avoid Vietnam, it was not true of Middlebury College boys, approximately 150 of whom, from the classes of 1964-68, served there.

Not me. I got out. I was not concerned with the Vietnam War, which was small potatoes, soon to be over we all thought, when I made this decision in 1965. I was not opposed to the military. Though I was no young scholar, I didn’t like the MS&T classes (Military Science and Tactics), which comprised one of my five courses each semester. I wanted to be in college. I would worry about the military when the time came. To the degree to which I thought about it, I thought I might like to heed JFK’s call and do a stint in the Peace Corps. It carried a draft deferment.

As an athlete in the 1950s and 60s, I had trained to a certain degree to be a warrior. My sports play was infused with military meaning. My mentors had been soldiers in WWII. Before my first varsity football game in high school, the coach, a WWII vet, told us to look at the player on either side of us and asked if we’d “like to share a trench with that guy.” The caddy camp I attended each summer as a teen-ager (eight summers!) was directed by two coaches from Bates College, whom I admired extravagantly. Both had been Marines in the South Pacific in War. The caddy camp itself, a single building, once a horse barn at the magnificent Poland Spring Hotel, was run like a military barracks. Camp leaders were Captains and Lieutenants. We had inspections and details. One of the Counselors was the Officer-of-the-Day. Our athletic contests at night were ferocious and often had combat elements – an obstacle course featured a “commando crawl,” capture-the-flag was accompanied by a “banzai” charge up the hill. General Eisenhower famously said, “the true mission of sports is to prepare young men for war.” We believed that.

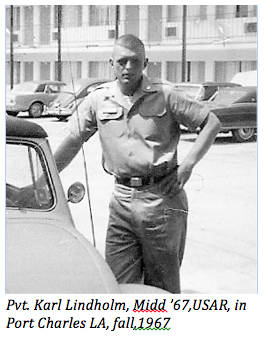

My time came when I graduated from Middlebury in 1967 and lost my student deferment. The need for soldiers in Vietnam was high. The draft rolls swelled. I was not a part of the burgeoning ant-war movement, but my sympathies were there. I couldn’t imagine choosing the alternatives to the draft available to me: jail or self-imposed exile to Canada, the choice of my college friend Dickie Hall. I would feel shame. I learned from a friend of my dad’s that the Army Reserve unit in my home town still had openings, unlike the situation in the rest of the country. Lewiston-Auburn, Maine was decidedly blue-collar and was not having difficulty meeting its draft quotas. The Reserves and the National Guard were havens from service in Vietnam: their active duty tour was only six months (followed by six years of meetings). Presidents Johnson and Nixon were prohibited from calling up the Reserves by the explosive political situation nationally. This act would be an intolerable escalation of the War (though in our recent Iraq War, up to 40% of the soldiers on duty there have been from the Reserves and National Guard).

So I joined the Reserve unit in Auburn, Maine before I even graduated from Middlebury.

A week after my graduation, I was at Folk Polk, Louisiana for Basic Training, and after that, a 14-week course at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio to become a field medic. I was a weekend warrior” and spent my annualArmy Summer camps at Fort Drum (Watertown, NY), Fort Devens (MA),  Fort Dix (NJ), Fort Storey (VA), and Fort Knox (KY). I was honorably discharged as a Spec 4 (Specialist 4th Class, or Corporal) in 1973. I do not put that on my resume. I have never claimed to be a “veteran.” I was always honest about my motivation: I went in the Army to get out of the war.

Fort Dix (NJ), Fort Storey (VA), and Fort Knox (KY). I was honorably discharged as a Spec 4 (Specialist 4th Class, or Corporal) in 1973. I do not put that on my resume. I have never claimed to be a “veteran.” I was always honest about my motivation: I went in the Army to get out of the war.

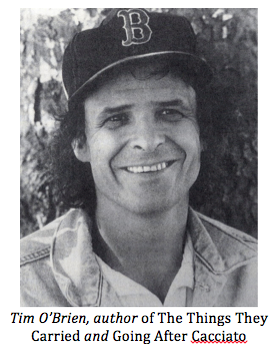

Of course, I have felt ambivalence about that choice, though not much guilt. I wondered how I would have responded in combat. I didn’t feel I could ask my friends who had seen action what it was like. I wanted to be their friend on another level. So I read. I read and read, Vietnam combat narratives, fiction and non-fiction. These narratives put me in the action – Philip Caputo’s preface to his Rumor of War established a context that struck me as real, true: “I could not deny the grip the war had on me,” he wrote, “nor the fact that it had been an experience as fascinating as it had been repulsive , as exhilarating as it was sad, as tender as it was cruel.” I read Tim O’Brien’s work – he was our brother who graduated from college (1968, Macalester, for him) and was drafted into the infantry. When he wrote that he went to Vietnam because he “couldn’t risk the embarrassment,” I thought,

“There but for the grace of God go I.” In “On the Rainy River” from The Things They Carried, he addressed the ambivalence of so many of us, concluding: “(I went) to Vietnam, where I was a soldier, and then home again. I survived but it’s not a happy ending. I was a coward. I went to the war.” From my reading, I came to appreciate what Caputo called “the ambivalent realities” of the War.

I taught a course on the Vietnam War for a first time in Winter Term, 1986, and it was a powerful experience for me and the 20 students who took the class. Vietnam vets were beginning to open up about their experience of the war after a prolonged silence. I invited a number to visit the class, including Jon Coffin ’67 and Fred Stetson ‘65, who spoke to the class every time I taught it subsequently. They spoke with a depth of emotion that was rare to encounter in an academic setting. I asked students to interview a vet and produce a written first-person account of their experience of the war. Many interviewed their fathers who spoke frankly for the first time to their children, perhaps because of the formality of the assignment (“it’s for a class, Dad”).

I taught this course on the literature of the Vietnam War at Middlebury College in the American Studies Program many times after that first experience. Because of our debt to Tim O’Brien and his powerful writing based on his experience as a “grunt,” a draftee, in Vietnam, I came to title the course. “Telling a True War Story: Vietnam.” O’Brien’s quest in The Things They Carried, his third work of fiction (of four) on the War, was to tell a “true” war story. As much as possible, that has been my goal too in teaching the course. The essay below from War, Literature, and the Arts, titled: “Dickie, Nick, Varsity Jim, and Bye-Bye: Teaching a True War Story,” goes into my experience teaching the Vietnam War.

the course. “Telling a True War Story: Vietnam.” O’Brien’s quest in The Things They Carried, his third work of fiction (of four) on the War, was to tell a “true” war story. As much as possible, that has been my goal too in teaching the course. The essay below from War, Literature, and the Arts, titled: “Dickie, Nick, Varsity Jim, and Bye-Bye: Teaching a True War Story,” goes into my experience teaching the Vietnam War.

This course on narrative presentations of the Vietnam War was a blessing for me: it gave my reading structure and purpose. I think I came to acquire both a visceral and deep empathy for what my friends and their comrades had gone through, and was able to share that understanding with Middlebury students, by putting together a stimulating reading list and classroom experience for them. I have also been able to do some writing of my own on the Vietnam War.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

“Dickie, Nick, Varsity Jim, and Bye-Bye: Teaching a True War Story”; (Dickie went to Canada; Nick was drafted and wounded in combat; Jim went into the radical anti-war movement and disappeared; Bye-Bye enlisted and was killed in Vietnam: they were schoolmates and friends whose choices symbolize the terrible divisions of that war), War, Literature, and the Arts, Fall/winter 1999

“A Jungle in There”: The Cross-Cultural Horror of the Vietnam War,” (friend and foe were impossible to distinguish, creating the volatile mix that produced a “cross-cultural disaster”), Phi Beta Delta International Review, Spring 1997

“Some Wounds are Hard to See: The Mind of the Warrior”: (“Though Stationed far from the battlefield, psychologist Jon Coffin ’67 mans a front line as perilous as any found in Iraq or Afghanistan”), Middlebury Magazine (cover story), May 5, 2006

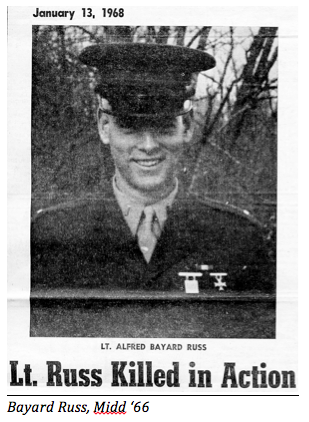

“Say Bye-Bye to a Two-Sport Athlete” (The annual award for the finest two-sport athlete at Middlebury isnamed for Bayard Russ, my friend, teammate, and fraternity brother, who died in Vietnam), Addison Independent, 22 January 2004

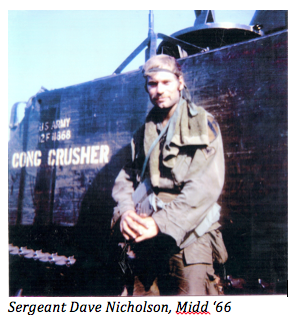

“Tales from the Nam: Taking a Charge” (Dave Nicholson, grunt in Vietnam, has written of his experience), Addison Independent,November 25, 2010

“Vietnam Stories (fiction), 1. Sportswriter at Khe Sahn; 2. Ward Nine, Cardiac Convalescence” (two very short stories connecting baseball to Vietnam), Elysian Fields Quarterly, The Baseball Review, spring 2002

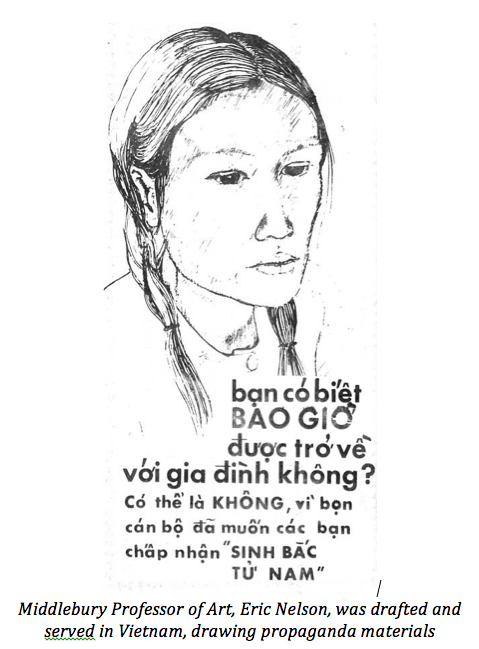

“Vietnam: the Next Generation,” (“As we are changed by that war, the children of that war are changing us”), profiles of four Middlebury students born in Vietnam who escaped to the U.S., one who earned a Rhodes Scholarship, Middlebury Magazine, fall, 1996