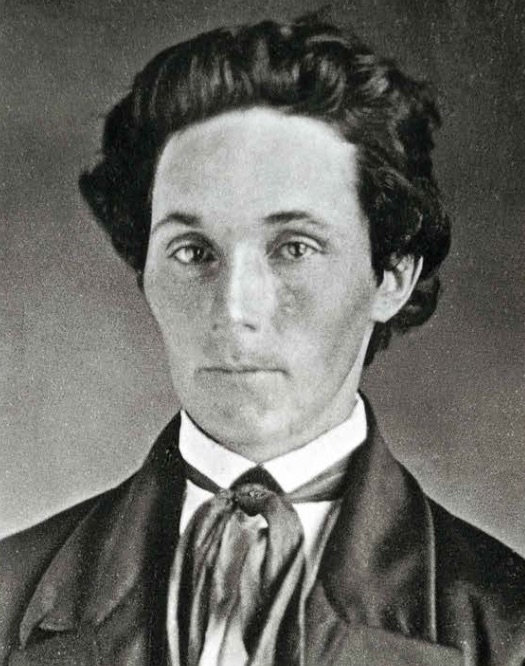

Edwin James. Source: Bain, The College on the Hill.

Edwin James was born in 1797 in Weybridge, where he grew up with twelve siblings on the farm that his parents Daniel and Mary James established along the Weybridge-Cornwall town line. James attended Middlebury College, graduating a year after his childhood friend Silas Wright in 1816. [ref] Washington, History of Weybridge, Vermont. [/ref] Each day he walked five miles from Weybridge to classes, [ref] Buckeye, The Education of Edwin James. [/ref] studying natural history under Frederick Hall, with whom he worked to produce the first catalogue of 551 plants native to Addison County. [ref] Bain, The College on the Hill: A Browser’s History for the Bicentennial, Middlebury College, 1800-2000. [/ref] After graduating, James began studying medicine in Albany, and also began going on geological and botanical field trips with his brother. [ref] Washington, History of Weybridge, Vermont. [/ref]

In 1820, Edwin James was invited to join Major Stephen H. Long as a field biologist on the first major expedition to the West since Lewis and Clark’s in 1806. [ref] Buckeye, The Education of Edwin James. [/ref] The party was tasked with exploring “from the Missouri westward to the Rocky Mountains to the source of the river Platte and thence by way of the Arkansas and Red rivers to the Mississippi.” [ref] Pammel, “Dr. Edwin James.” [/ref] Along the way, James collected botanical specimens and kept a field journal in which he recorded and named more than 500 plants previously unknown to Western science, among them the Rocky Mountain blue columbine, which today is the state flower of Colorado. In the Rockies, Edwin James also became the first recorded person to summit Pikes Peak in 1820, and the mountain was named in his honor until it was later renamed. It was also during this expedition that James began to recognize the injustices of white settlers driving native peoples from their lands as well as the “wanton destruction” of bison herds in the West by white hunters. One biography of James notes his exceptionally compassionate nature, recounting that he found himself “caring for the horses and dogs on the expedition, when others ignore[d] them.” [ref] Buckeye, The Education of Edwin James. [/ref]

The James family homestead. Date unknown, pre-1907. Source: Pammel, “Dr. Edwin James.”

After returning from his expedition through the West, Edwin James was ”appointed an army surgeon and was stationed at forts on the upper Mississippi.” [ref] Bain, The College on the Hill [/ref] During his ten years there, [ref] Ibid. [/ref] he also became close with John Tanner, a white man from Ohio who “had been captured by Indians” [ref] Buckeye, The Education of Edwin James. [/ref] and spent 30 years with the Ojibwe people, who “became much attached to him and treated him as one of their own tribe.” [ref] Pammel, “Dr. Edwin James.” [/ref] James learned about local indigenous cultures and languages, and became increasingly sympathetic towards indigenous peoples and outraged over “the treatment often given these native Americans, particularly the way they were bribed to give up land for guns and liquor.” [ref] Washington, History of Weybridge, Vermont. [/ref] With Tanner’s help, James translated the first Ojibwe version of the New Testament, and wrote several other books about Ojibwe linguistics as well as an account of Tanner’s life as a captive. In it, he offers “as harsh an indictment of white American civilization we can find in the nineteenth century.” [ref] “Few will read it [Tanner’s story] without some sentiments of compassion for a race so destitute, so debased, and hopeless; gladly would we believe, it may have a tendency to call the attention of an enlightened and benevolent community to the wants of those who are sitting in darkness.” [/ref] James highlights “the capitalist greed of those in the fur trade, who in order to control Indians who gather pelts encourage the use of alcohol among them.” He also “damns Christianity for its callous convenience in using religion to subjugate Indians.” [ref] Buckeye, The Education of Edwin James. [/ref] After leaving the army, James returned to his farming roots and established a home in Iowa, where he ran a station on the Underground Railroad. [ref] James demonstrated himself to be equally fierce in his stances regarding the status of African Americans at the time, writing: “We must elevate the negro or go down to degradation and servitude with him.” [/ref] [ref] Bain, The College on the Hill. [/ref] While his ideas may have been unpopular at the time—even driving him to become reclusive in his later years—he “spoke the truth as he knew it with consequences he did not anticipate.” [ref] Buckeye, The Education of Edwin James. [/ref] While “his strict insistence on honesty and temperance offended those who wanted to profit by exploitation and corruption,” many of his works in botany and linguistics remain “classical sources of information.” [ref] Washington, History of Weybridge, Vermont. [/ref] As one biographer summarized his life’s work, “In his defense of the Native American and the environment, his rejection of slavery and American exceptionalism, James is a man of our times who fights for the legacy that is ours.” [ref] Buckeye, The Education of Edwin James. [/ref]

Rocky Mountain blue columbine (Aquilegia caerulea).