—

A far left Tunisian politician, Belaid was a leader of the secular Democratic Patriots Movement. Belaid spoke out against the Ben Ali Regime and was a harsh critic of the Salafists, or fundamentalist Islamists. After the beginning of the Arab Spring, on February 6, 2013, Belaid was fatally shot outside of his home. His assassination served as the final straw in the new Tunisian government’s commitment to eliminating the remnants of the old regime, and to form a “national unity” government.

http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2013/02/20132610565078813.html

Born March 29, 1984, Mohamed Bouazizi was a street vendor whose politically motivated self-immolation on December, 2010 served as the trigger for the Tunisian Revolution of 2011. Buoazizi’s act of protest and consequent death turned him into a symbol of the Tunisian people’s struggles against unemployment, oppression and police brutality and corruption.

The oldest of six children, Mohamed Bouazizi grew up in Sidi Bouzid, a town in the center of Tunisia. As a consequence of his father’s death and of his family’s financial struggles, Buoazizi began working as a street vendor at the age of 10.

As he became his family’s main source of income, Mohamed Bouazizi stopped his high school education in order to provide for his step-father, mother and five younger siblings. However, Sidi Bouzid’s staggeringly high unemployment and corruption rates led to the young Tunisian’s growing frustration.

On December 17, 2010, a confrontation erupted as a municipal inspector called Faida Hamdy seized Bouazizi’s fruit-weighting scales. Eye witnesses and relatives say Hamdy humiliated and struck Bouazizi. After the incident, the street vendor reported and repeatedly demanded the town official’s involvement in what was clearly a case of abuse of authority. However, Bouazizi’s efforts were ignored. In response the young Tunisian set himself on fire outside of the governorate building.

Shortly afterwards protests erupted in Sidi Bouzid and then to other cities and towns across Tunisia: Buoazizi became a symbol of Tunisians’ frustration with corruption and the authoritarian rule of President Zine el Abedine Ben Ali, who had been in power for almost a quarter of a century. Under the mounting pressure of the mass demonstrations across the country, the dictator visited Buoazizi’s hospital bed. Mohamed Bouazizi died on January 4th, 2011.

Watson, Ivan. “The Tunisian fruit seller who kickstarted the Arab Spring”. CNN. March 22, 2011. http://www.cnn.com/2011/WORLD/meast/03/22/tunisia.bouazizi.arab.unrest/

Ryan, Yazmine. “The Tragic Life of a Street Vendor”. Al Jazeera. January 20th, 2011. http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2011/01/201111684242518839.html

The founder of the People’s Movement, Brahmi served as general secretary of the party after its founding during the early stages of the Arab Spring. Up until that point, Brahmi was an outspoken socialist and a critic of the Ben Ali regime. He never actively spoke out against Islamists, and was actually quite close with a few members of the Ennahda party, the group in power after the revolution. Brahmi was assassinated on July 25, 2013, a few months after another left-wing opposition leader, Chokri Belaid, was murdered. It is believed that the same man, a Salafist supporter, was responsible for both murders. Brahmi’s untimely death sparked massive protests across Tunisia, shining a light on the mounting tensions between vastly different political beliefs.

http://www.tunisia-live.net/2013/07/25/whos-who-mohamed-brahmi/

Respected lawyer and politician, Samia Hamouda Abbou was a founding member of the National Council for Liberties and joined the Congress for the Republic (CPR) in 2006. She attended primary and secondary education in Tebourba before receiving her Faculty of Law of Tunis and Advanced Studies Diploma in 2010.

On December 27, 2011, Moncef Marzouki became interim President of Tunisia, leaving an open seat in the Constituent Assembly. Samia Abbou readily replaced Marzouki in the Constituent Assembly, representing the Nabeul Governorate of north-eastern Tunisia. She was part of the CPR party until 2013, when she and her husband, Mohamed Abbou, left and founded the Democratic Current political party, otherwise known as Attayar. Ideologically driven by principles of social democracy, social liberalism, progressivism, nationalism, and Pan-Arabism, Attayar currently has 3/217 seats in parliament. Samia Abbou holds one of these seats, elected in the 2014 elections. She is an active member of the general legislative committee of the National Constituent Assembly, a group working to schedule poll dates, set campaign finance rules, determine time and order of presidential and parliamentary elections, and delineate official term periods.

http://www.tunisia-live.net/2014/02/05/electoral-law-next-step-for-tunisian-assembly/

http://majles.marsad.tn/fr/deputes/4f798b24b197de7f0c000000

http://www.attayar.tn/

Text by Margot Masinter

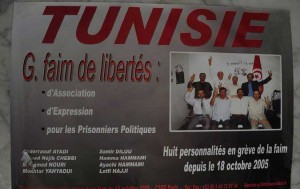

18 October 2005 Coalition for Rights and Freedoms in Tunisia RCD (Democratic Constitutional Rally)

18 October 2005 Coalition for Rights and Freedoms in Tunisia RCD (Democratic Constitutional Rally)

The 18 October Coalition for Rights and Freedoms in Tunisia was a consensus between different political parties (including leftists, liberal democrats, and Islamists) who resolved to put aside differing ideologies to focus on common goals. They unified as a response to repression by the essentially one-party state under Ben Ali of the Dustour Party, and the limits placed on political pluralism and freedom of opposition.

There were many events that led up to the coalition. In 2005, lawyers protested the arrest of Mohammad Abu, who in an article spoke out against the regime. On October 18, 2005, the ongoing repression and lack of political freedom prompted eight national personalities from different political parties to go on a hunger strike. Their goals were freedom of organizations, freedom of information and expression, and the release of political prisoners. This public hunger strike brought the injustice under Ben Ali to the public eye. The coming together of different political parties of the opposition rejected the notion under Ben Ali that Islamism was the greatest danger to Tunisia, and that instead political repression was crippling Tunisia.

The strike ended in the 18 October Coalition for Rights and Freedoms. Their focus was on unity, but also recognized the right to disagree. The coalition believed that the exclusion of Islamists contradicts with democratic principles, and may in radicalization if the Islamists are shut out of the political process.

In response to the coalition, “The Progressive Democratic Coalition” was formed. This coalition was suspicious of the involvement of Islamists and resisted the re-emergence of Islamism.

The coalition was faced with the external obstacle of a tight blockade, and internal obstacle of staying clear of its objectives.

Text by Chi Chi Chang)

—

Source: http://www.arab-reform.net/18-october-coalition-rights-and-freedoms-tunisia

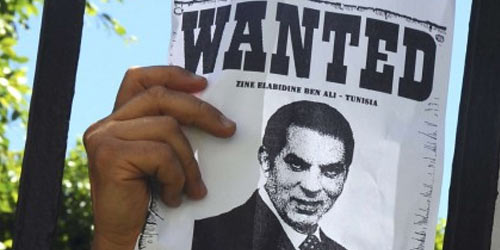

Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali

Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali

Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali is a former president and the last one to serve prior to the introduction of the new Tunisian governing order. His platform rested upon controlled “democracy,” staunch secularism, Tunisian nationalism, state capitalism, and anti-Islamism. Having unseated the nation’s first post-independence president in a bloodless coup, Ben Ali served from 1987 until 2011 as an authoritarian strongman with no real electoral opposition. In addition to his aforementioned political ideology, Ben Ali’s regime was also characterized by widespread corruption, misuse of public offices and , entrenched cronyism, and violent repression.

Though it is tempting to portray him as the personification of pure greed, violence, and lust for power, it appears that Ben Ali (as well as those who supported him and those who to do so), to a certain extent, believes that his was necessary to not only modernize and further develop Tunisia, but also to prevent the emergence of militant fundamentalist Islam. However, this is not a unique position amongst autocrats in Muslim-majority nations; it is an attempt to adapt a decades-old utilitarian Nasserism to the modern era, through the medium of steadfast support for the global “war on terror.” Though this guiding mentality has a certain degree of merit (as radical Islamic militancy has had a notable presence in the post-Spring Arab world), when taken in tandem with the countless abuses he inflicted as president and the grotesque personal wealth he gained through such dereliction of duty, Ben Ali has ceded any legitimate moral claim he may have had in defense of his tenure in power.

(text by Elias Gilman)

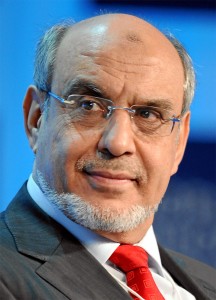

Mustapha Ben Jaafar

Mustapha Ben Jaafar

Mustapha Ben Jaafar was the president of the Constituent Assembly of Tunisia during the time of the transition from November 2011 to December 2014. This was due in part to his party, the Democratic Forum for Labor and Liberties, winning seats in the Assembly. His party was a member of the oppositional 18 October Coalition for Eights and Freedoms against the Ben Ali regime. After the revolution it became clear that Ben Jaafar and his party were representative of the secular center left ideology. With the support of his own party and the backing by Ennahda, he was able to push the agenda on the transitional process as part of the former Troika government. More recently, he has shown interest in running for a consensus president candidate, but is uncertain if his support is gained through the distaste of Beji Caid El-Sebsi’s push for presidency. During his time as president he made a controversial decision to suspend NCA sessions until he believed all political parties joined a national dialogue. He wanted to create a consensus for Tunisia as he stated, “I have my this decision for the sake of serving Tunisia. My own aim is Tunisia. My duty is assuring and inuring the democratic transition”.

Ben Jaafar’s thoughts on the transitional government are those of success but he believed that the transitional phase would not take the traditional form of democracy and there were disputes between the government and the opposition. He believes the transition is not the best performance for in his mind the Tunisian politicians lack sufficient experience in managing state affairs, “since most were either behind bars or in the opposition”. This has truth to it, as it was clear much of the debates that occurred during the transitional period were centered on religion and its place in government instead of other aspects such as economy, environment, and education.

(text by Guilherme Araujo)

—

Source:

http://www.aawsat.net/2014/06/article55333724

http://www.thetunistimes.com/2013/08/tunisia-mustapha-ben-jaafar-to-suspend-parliament-activities-until-national-dialogue-resumes-63030/

http://www.aljazeera.com/category/person/mustapha-ben-jaafar

Ben Youssef began his political career under Habib Bourguiba as the Secretary General of the Neo-Destour Party in 1950. However, throughout the process of Tunisian Independence from France (1952-1956), Youssef found himself opposed to the policies of Bourguiba.

Despite the “Treaty of Friendship and Good Neighborliness”, the relationship was protectoral only in name. In practice, “it became”—in the words of Ben Youssef himself in his call for complete independence—“an instrument of economic exploitation for the benefit of the French colonial settlers in the country […] [T]he French protectorate in Tunisia ultimately led to the transformation of the country into a colony administered directly by France.” This invasion of his country’s sovereignty infuriated Ben Youssef and for him the only viable solution was complete independence from France. This put him at odds with Bourguiba who was willing to take a less aggressive negotiating stance and entertained the possibility of “less than full” independence.

Ben Youssef identified increasingly with an Arab and Islamic perspective while his rival was determined to turn a new page with the relationship between Tunisia and France. This created a polarizing dialogue between the Youssefists and the Bourguibists. On the one hand, Bourguiba came to represent modernization of Tunisia. Such modernization was often likened to westernization, in direct conflict with Arab and Islamic values. These perspectives were pitted against Ben Youssef’s, which were strongly based in a strong Arab and Islamic identity. Ben Youssef’s Arab Nationalist identity was Bourguiba’s main opposition during his presidency.

The interplay between these two camps has permeated the modern political climate in Tunisia, and in many ways this modern history gave rise to some underlying but fundamental issues in the Tunisian Revolution. Even today, long after the assassination of Ben Youssef, we see the conflict cropping up again in the most recent election of Essebsi and his race against Marzouki, the former representing the Bourguibist position and the latter the Youssefist. Although it is hard to tell right now, Essebsi is from the old regime, and is assumed to have similar secularist views on the future of the country as Bourguiba did. However, Marzouki, in calling for a true democracy, believes there is a place for the Islamists, or Ennahda, at the political table. During his term as president, Marzouki took strides to apologize to the families of those oppressed under Bourguiba’s persecution of the Youssefists. While Marzouki’s dialogue may be more moderate than Ben Youssef’s, the message is clear: forced secularism is a violation of human rights.

(text by Jana Parson)

——

Sources:

Youssef, Salah Ben. “TUNISIA’S STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE.” Pakistan Horizon 7.2 (1954): 56–61. Print.

Gana, Nouri. The Making of the Tunisian Revolution: Contexts, Architects, Prospects. , 2013. Print.

http://www.leaders.com.tn/article/bourguiba-ben-youssef-le-grand-pardon?id=7972

Habib Bourguiba

Habib Bourguiba

Habib ibn Ali Bourguiba (1903-2000) was Tunisia’s first president and champion of independence. History remembers Bourguiba as both the man that freed Tunisia from colonial rule, but also as the autocrat who created a monopoly of political power that would later be exploited by the dictator Ben Ali.

After developing an affinity for politics studying in Sorbonne in Paris, in 1927 he returned to Tunisia and joined the struggle for independence. Bourguiba quickly rose to prominence and founded the Neo-Destour party after he clashed with the leadership within the old Destour party. For Bourguiba, the old Destour party represented primarily the of the landed elite in Tunis. If the liberation movement was to gain enough popular support, Bourguiba knew that the party would have to reach a larger spectrum of the population.

After Bourguiba’s Neo-Destour party gained real momentum and potential for change, he was quickly exiled by the French. However, this banishment did not have the intended effect, as the movement towards independence did not down. Bourguiba would be arrested twice more following an interm period during WWII until finally the French caved to the rising independence movement in 1954.

During the transition, one of Bourguiba’s close political allies, Ben Youssef, conflicted with Bourguiba over residual French presence in the Tunisian government. Bourguiba’s response was not to confront head-on this new contender, but to politically out-meneuver Youssef. Because Bourguiba held public favor as the leader of the independence movement, he had Youssef expelled from congress, in move that would set a precedent of inhibiting the growth of opposition movements against the Bourguiba regime.

By 1957, the first presidential elections in Tunisia were won by Bourguiba. Initially, the long presidency of Bourguiba was filled with democratic accolades such as the liberalization of women’s rights and the acceptance of Islam as a cultural identity. However the economic policy of the early Bourguiba reign was a complete failure that led to a growing opposition. A failed socialist experiment and a consecutive depletion of domestic led the country into an economic crisis in the 1980’s. To maintain the monopoly of power in the new Destourian Socialist Party, Bourguiba grew more authoritarian and consolidated political power in the presidency. Opposition leaders were convicted of defaming the president and what used to be free elections were marred by allegations of fraud.

By 1989 unemployment, inflation, and rising food prices brought the popular support of Bourguiba to an end. In fact, all Zine El Abidine Ben Ali had to do to oust the current president for life was to remark how his old age made him incapable of acting as president.

Bourguiba’s legacy on Tunisia is both positive and negative. While he led the country through a transition to independence, he instilled a dominant single-party government that became increasingly authoritarian. His work in granting women’s rights such as the right to divorce and the religious freedom he advocated for were positive change, although it seems his intentions in doing so were to monopolize public support. Today, politicians are once again aligning themselves with the Bourguiba of old to garner public support, but they are careful not to bring to light his more authoritarian qualities.

(text by Matt Capozzoli)

—-

Sources

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/75869/Habib-Bourguiba#toc278558

http://www.tunisia-live.net/2013/04/09/reflecting-on-bourguiba-13-years-after-his-death/

Destour & Neo-Destour

The Destour was originally founded in 1920 as a left-wing political party—The Constitutional Liberal Party (CLP)—to rid Tunisia of France’s colonial occupation and influence. Members of the CLP, it seems, were constitutionalists: the word Destour literally translates to constitution. Finally, the makeup of the CLP was largely youth. The party was upheld by students and academics from Tunisia’s University of Ez-Zitouna and Sadiki College.

In 1934 the party split, forming the Neo-Destour party. The Neo-Destour party also sought to French “protectionism” over Tunisia. After Neo-Detour led independence from France, the party developed into Tunisia’s first socialist party (Ben Youssouf was expelled shortly afterwards), the Socialist Destourian Party, under President Bourguiba. It transformed again after Ben-Ali seized power from Bourguiba, becoming the Rassemblement Constitutionel Démocratique—Tunisia’s authoritarian ruling party under President Ben-Ali until 2011.

The great irony of the Destourian Party’s fate is that its founders would never have aligned with either Bourguiba or Ben-Ali. Sure, the CLP transitioned into the SDP and eventually into the RCD because it had attained its initial goal of expelling the French colonists. But the spirit of the SDP and RCD was far-removed from that of the CLP. I imagine that if the original Destourians were around in 2011, they would have aligned with Tunisian revolutionaries rather than with the modern manifestation of the CLP as defined by Ben-Ali. Much like the original Destourians, Tunisia’s revolutionaries were young students who sought freedom from an oppressive regime alongside a new constitution.

(Text by Oliver Mayers)

Rachid Ghannouchi is well known for being the co-founder of the moderate Islamist political party, Ennahda. By establishing the Ennahda in 1981, he aimed to oppose the ruling government that had been ruled by Bourguiba and Ben Ali. In his writings, such as “The Founding Communiqué of the Islamic Tendency Movement,” Ghannouchi called for progressive aspects in Islamic reform that emphasized democratic values. He is a supporter of workers’ rights, unions, and the elimination of social injustice. Ghannouchi’s views on women rights contrasts significantly from those of other founders of Islamist movements. Ghannouchi insists that Islam acknowledges rights and privileges for women, including education and their preferable choice of clothing. He also believes that a pluralistic Muslim society, which Tunisia should strive towards, should work towards cooperating with non-Muslim citizens instead of oppressing their views.

Following Ben Ali’s departure in the aftermath of the Tunisian Revolution, Ghannouchi returned to Tunisia as a politician and intellectual thinker from his twenty-two-year exile in London. Ghannouchi’s party, Ennahda, played a major role in drafting the new Tunisian constitution. During the writing of this new constitution, Ghannouchi stressed his beliefs that combined Islamic principles with democratic values and human rights.

(Text by Jonathan Yun)

——

Sources:

http://www.voanews.com/content/qa-tunisias-constitution/1861013.html

http://gulfnews.com/life-style/people/a-genuine-islamist-democrat-1.865958

http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/an-interview-with-tunisias-rachid-ghannouchi-three-years-after-the-revolution/2013/12/12/7aaaaa5a-62cf-11e3-a373-0f9f2d1c2b61_story.html

Hamadi Jebali

Hamadi Jebali

Hamadi Jebali is a Tunisian-born politician who was the Prime Minister of Tunisia from December 2011-February 2013. He was the Secretary-General of the Ennahda until he left his party in December 2014 in the course of the Tunisian presidential election, 2014.

His resignation from the post of Prime Minister is particularly important to take note of. As of February 2013, Mr. Jebali had been trying to form a new coalition in response to the political crisis sparked by the killing of opposition leader Chokri Belaid. This shocked the nation and resulted in rioting and strife. In response to the assassination, Jebali offered to dissolve the fractious coalition and put together a temporary new government of technocrats to smooth over the cracks until they could fix a date for elections. While the opposition welcomed the move, a majority in the Ennahda party rejected it, saying the party had not been consulted. Tensions appeared within the party as its leadership organized two street demonstrations in which protesters and leading figures called for politicians to stay in charge of the government. Jebali had effectively been overruled by his party, despite his number two position within the party, and said he would quit if Ennahda did not back his plan for a cabinet of technocrats. Upon his resignation, he remarked that “The failure of my initiative does not mean the failure of Tunisia or the failure of the revolution,” in a reference to the popular unrest two years ago that ousted autocratic leader Zine al-Abidine Ben Al (BBC).

Despite his desire for a more stable Tunisia, his resignation in fact had very negative impacts on the country. The political stalemate prompted an international ratings agency to downgrade Tunisia’s credit rating, putting further strain on its struggling economy (The Guardian). Thus it is important to note that his resignation had important social, economic, and political repercussions; it was not simply a political tool. There was hope that his resignation might spark political talks to reform the nation. In 2013 Jebali insisted that he would not lead another government without assurances on a date being set for fresh elections and a new constitution (The Guardian).

(text by Samantha Simas)

—–

Sources:

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-21508498

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/feb/20/tunisia-prime-minister-turmoil

Maya Jribi

On December 25th, 2006, Maya Jribi was appointed Secretary General of the secular Progressive Democratic Party (PDP), making Tunisian history as the first woman to head a major political party. As the Secretary General of the PDP, Jribi aimed to gather “different currents, from former Marxists to progressive Muslims to activists for democracy” in order to push for a left-of-center Tunisia.

Born in 1960 to an Algerian mother and Tunisian father, Jribi was politically active from a young age. Under the Bourguiba regime of the early 1980’s, Jribi joined the Tunisian League for Human Rights, founded the Tunisian Association of Research on Women and Development, worked as a fundraiser for UNICEF, and wrote for the democracy-advocating publication Errai (L’Opinion). This activism continued into the Ben Ali regime when Jribi, along with lawyer Ahmed Najib Chebbi, founded the Progressive Socialist Rally (RSP)—the precursor party to the PDP.

Despite being a legal opposition party to Ben Ali’s Constitutional Democratic Rally (RCD), the PDP was still subject to various forms of political repression under Ben Ali. When a 2007 court decision forced the PDP to move its headquarters from Tunis, Chebbi and Jribi led a successful 20 day hunger strike to reverse the ruling.

Following the 2010-2011 revolution, Jribi headed the PDP’s electoral list in Ben Arous, gaining a spot in Tunisia’s first National Constituent Assembly. When both the PDP and another secular party, Afek Tounes, merged with the Republican Party in 2012, Maya Jribi continued in her political leadership, assuming the position of Secretary General in the renovated Republican Party. The Republican Party now acts as one of the main opposition groups to the Islamist Ennahda Movement.

Jribi is a dedicated feminist and holds a degree in biology from the University of Sfax, in Sfax, Tunisia.

(text by Cole Bortz)

—–

Sources:

http://www.tunisia-live.net/2012/01/11/major-tunisian-secular-parties-announce-merger/

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/oct/19/tunisia-elections-the-key-parties

http://www.tunisia-live.net/whoswho/maya-jribi-2/

UGTT logo. Source: Wikipedia

UGTT, Farah Hached

The Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail (UGTT), the Tunisian general labor union, formed in 1946 under Farhat Hached, was the result of the Tunisian labor movement of the 1920s (Hamrouni et al. 30). Its establishment was closely linked to the Tunisian nationalist movement for liberation (Hamrouni et al. 30).

Under Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s regime, the UGTT operated under a notably consequentialist methodology. The federation backed the regime because of the lacking of any meaningful political pluralism that transcended symbolism. While voting for Ben Ali, the federation simultaneously bargained with the state and industrialists to augment the material conditions of workers (Hamrouni et al. 31). It is essential to understand that the attitude of the UGTT in the revolution was spontaneous and subsequently developed alongside those on the ground (Hamrouni et al. 31). Despite Ben Ali’s attempts to subdue the UGTT leadership, internal turmoil in the union was not kept at bay, and consequently the union retained some degree of contestation, protest and opposition under Ben Ali (Zemni 140).

After Ben Ali had fled Tunisia, the UGTT quickly joined different protest movements against the transitional governments while simultaneously receiving internal and external criticism (Zemni 140). The UGTT wanted a complete severance from the Ben Ali era Tunisia and its neoliberal developmental policies (Zemni 141). Today, the UGTT remains one of the few institutions capable of mobilization against the “derailment of revolutionary aspirations” (Zemni 142).

The union remains one of four institutions comprising the Tunisian National Dialogue, along with Utica, the Tunisian Human Rights League (LTDH), and l’Ordre des avocats (“Tunisie”).

(text by Benjamin Hawthorne)

——

Work Cited

Hamrouni, Abdellatif, Najoua Makhlouf, Sami Aouadi, and Kheireddine Bouslah. “Tunisian Labor Leaders Reflect Upon Revolt.” Middle East Report People Power 258 (2011): 30-32. JSTOR. Web. 5 Jan. 2015.

“Tunisie: Incertitudes Autour Du Démarrage Du Dialogue National.” Al Huffington Post. HPMG News, 4 Oct. 2013. Web. 11 Jan. 2015.

Zemni, Sami. “From Socio-Economic Protest to National Revolt: The Labor Origins of the Tunisian Revolution.” The Making of the Tunisian Revolution: Contexts, Architects, Prospects. Ed. Nouri Gana. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013. 127-146. Print.

Listening to former president Moncef Marzouki in English on his trip to America does provide important context for what he says there. It is likely that his primary objective in these interviews was to appeal to potential investors in the US and Europe to come to Tunisia and provide jobs. In addition to touting Tunisia’s educated, homogenous population he also makes the moral appeal that democracy is impossible without an improvement of people’s lives and the economy. He says “supporting Tunisia is really peace and democracy in the whole region” (CFR).

He also addresses the security concerns that are plaguing the country. He emphasizes the necessity of collaboration with regional partners, particularly Algeria, in dealing with the ongoing instability going on in Libya. He is committed to sharing Tunisia’s relative prosperity with the two million Libyan refugees in the country, but acknowledges the logistical difficulties.

To terrorists he says that no act of terrorism will halt the countries movement towards democracy and stresses that (in September of 2014) will take place whatever threats or actions of violence are taken.

That being said, Marzouki says that the economy was a higher priority of his transitional government than . Focusing on long term solutions to and political problems was his focus as interim president.

While women’s political rights have been a part of Tunisian discourse for decades, Marzouki chooses to focus on two things less frequently discussed. Political rights are “on paper” (CFR) but don’t address problems like violence against women and child abuse or the fact that the majority of the poor in Tunisia (and around the world) are women. These social problems are compounded by access to healthcare and the job and actual political .

In an interview with the Atlantic Council Marzouki stressed that not all Islamist ae created equal. Complete exclusion of all types of Islamists from the political process, like the current situation in Egypt, further radicalizes otherwise moderate populations and forms a weak basis for democracy.

Marzouki’s father was a supporter of Ben Youssef, which lead to his family’s emigration to Morocco in the 1950’s. He studied medicine in France before returning to Tunisia in 1979 where he joined the Tunisian League for Human Rights. He founded the political party Congress for the Republic in 2001, and when it was outlawed in 2002 he moved to France to running it. He became interim president through a Troika government agreement in December 2001 until the 2014 November-December presidential election when he was defeated by Beji Caid Essebsi.

(Text by Kathy Preston)

——

Sources: http://www.cfr.org/tunisia/tunisian-president-marzouki-elections-economy-regional-stability/p33468

Tunisia’s Democratic Successes: A Conversation with the President of Tunisia Mohamed Moncef Marzouki

The National Constituent Assembly

The people of Tunisia elected the National Constituent Assembly of Tunisia on October 23rd 2011, after a revolution that sparked the retreat of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. The National Constituent Assembly of Tunisia consisted of 217 representatives, 199 residing in Tunisia and 18 outside the country. There were many parties and groups of citizens represented, the majority being the Ennahda Movement, a moderate Islamist group.

The assembly was tasked with creating a new constitution that would better represent the country of Tunisia after their revolution. The parliament was founded on November 22, 2011, with president Mustafa Ben Jafar, and vice presidents Meherzia Labidi Maiza and Larbi Ben Salah Abid. The assembly was divided into six different sections, each focusing on a specific theme of the new constitution.

The drafting of the constitution began on February 13th, 2012, and took longer than expected to complete. The process was delayed when Mohamed Brahmi, an opposition deputy, was assassinated in July 2013. This caused other opposition deputies to boycott the assembly for multiple months. After much debate, on January 26th, 2014, the constitution was finally passed.

The debates about the contents of the new constitution exposed many opinions and a great number of arguments. However, in the end, the National Constituent Assembly successfully created a constitution with many important qualities and changes. It integrated laws corresponding to issues of place of religion in political life, the appointment of judges, executive powers and other presidential qualifications. It also allows for fundamental rights, liberties, and a political system representative of a democracy.

The National Constituent Assembly created a new constitution for the country of Tunisia that highlighted many of the problems the populous had with the previous government.

(Text by Jake Stalcup)

—–

Sources: https://globalvoices.org/2014/01/27/tunisias-constituent-assembly-adopts-new-constitution/

http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2014/01/tunisia-assembly-approves-new-constitution-201412622480531861.html

http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/world/2011-10/23/c_131206984.htm

—–

Ali Laarayedh

Ali Laarayedh

Ali Laarayedh was born in Medenine on 15 August 1955. In 1980 he received a maritime engineering degree. Despite his diploma, Laarayedh pursued a career in politics where he served as an advocate for the Ennahda movement. Laaryedh wanted to promote a moderate form of Islamist government that he believed would coexist with democracy. However, after the coup d’Etat that put Ben Ali in power, Laarayedh was imprisoned from 1990 to 2004 under the new regime. After the Tunisian Revolution and Ben Ali’s expulsion from office, Laarayedh was appointed as the head of the Ministry of Interior during the transitional government. In 2013, Laarayedh was appointed the post of Prime Minister. He held this position until 9 January 2014 when he stepped down due to political unrest. He was aware of his position in the changing government and refused to anger the Tunisian people by over serving his term during the transitional period. Laarayedh wanted Tunisia to be a model for a truly democratic state and it is for this reason that he is viewed positively by the Tunisian people. He is currently an MP in the Tunisian government and lives with his three children and wife who is a medical technician.

(Text by Adam Fisher)

—–

Sources: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/26/world/africa/ali-laarayedh-leads-the-tunisian-agency-that-once-jailed-him.html?_r=1

http://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/middle-east/2014/01/09/Tunisia-s-Islamist-PM-steps-down-as-unrest-mounts-.html

http://www.leaders.com.tn/article/10860-biographie-de-ali-larayedh

—–

RCD (Democratic Constitutional Rally)

The Democratic Constitutional Rally or the RCD (formally called in 1988) was a Tunisia political party originally formed in 1934 (under the name Neo-Destour) by younger members of the conservative Destour party. The Destour party was against the French protectorate and sought total independence from France and the RCD party would initial follow these same ideals. The RCD would be the primary political party that led the campaign for a Tunisia independence from France in 1956 and would remain in power until the revolution in 2011.

The RCD (still known as Neo-Destour during this time) took governmental power after the Tunisian independence in 1958 with Habib Bourguiba as its leader. In 1963 the party declared itself the sole political party in Tunisia and took complete control of all governmental activities with a newly adopted political strategy which was an aspect of socialism (the party would also be renamed to the Destourian Socialist Party or the PSD).

The party would deteriorate overtime due to internal turmoil of high ranking members and in 1987 Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali executed a constitutional coup and replaced President Bourguiba on the grounds that he was too old to govern. In 1988 Ben Ali, the president of Tunisia, and his party (know under the final name of The Democratic Constitutional Rally or the RCD) governed Tunisia. It would be under Ben Ali’s regime that Tunisia would become a totalitarian state. The party remained closely tied to the ruling regime and its loyalty was rewarded with “having a dominant position in the majority of national matters”.

In early 2011, after 23 years of rule, the RCD would lose its power after Ben Ali was removed from office because of a revolt by the people of Tunisia. The RCD would still be present during the interim government, but ultimately would be dissolved by the Tunisian Court on March 9th, 2011.

(Text by Jon Hurvitz)

Sources:

http://www.britannica.com/topic/Democratic-Constitutional-Rally

http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/tunisia/rcd.htm

—–

Sihem Ben Sedrine

Sihem Ben Sedrine is a journalist and human rights activist who has spent over twenty years defending free speech and exposing various human rights violations in Tunisia. Sedrine co-founded the National Council for Liberties in Tunisia (CNLT) in 1998 as well as the Observatory for Freedom of the Press, Publishing, and Creation (OLPEC), and Kalima, an independent news organization. The CNLT recorded and made the human rights conditions in Tunisia available to the public. While the Ben Ali regime refused to legally recognize the CNLT, it was still able to contribute to reports on the human rights situation during the oppressive regime. Due to the nature of these reports and investigations, Sedrine’s safety was repeatedly threatened. After facing threats for two years, she was thrown in jail for two months in 2001 for criticizing the Tunisian government on television.

As pressure from authorities increased, Sedrine left Tunisia for exile in 2009 where she remained until Ben Ali’s departure. In 2011, she returned to Tunis to continue work on freedom of speech in the Arab world. As the current head of the Truth and Dignity Commission, Sedrine works to bring the businessmen and politicians who profited under Ben Ali to justice.

Because of her valuable contributions to reports on human rights and her efforts to protect freedom of speech, Sedrine has received international recognition. She has been given numerous awards by international journals and corporations for her remarkable journalism under an oppressive regime.

(Text by Ella Marks)

Sources:

https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/08/13/sihem-bensedrine-tunisia

http://www.ifex.org/tunisia/2001/06/27/sihem_bensedrine_jailed_threats/

—–

Source: Wikipedia

Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia

Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia, AST (or supporters of Islamic law in Tunisia), is a Salafist organization within Tunisia that seeks to implement Sharia law in Tunisia. They share the same name and ideas as the groups in Libya and Yemen, ASL and ASY, but their connection is unknown. Shortly after the revolution in 2011, led by Abu Iyadh al-Tunisi, AST began gaining support, having around 45,000 members in 2012. Most members participate by spreading their ideology through lectures, charity, and publications. According to Abu Iyadh, the group is based on the idea that “Tunisia is a land of dawa (charity in the name of Islam) not a land of jihad.” But some members decide to resort to violence, and although they have not claimed any attacks to be theirs, the Tunisian government has blamed them for multiple attacks. These included attacks on the U.S. embassy in Tunis, as well as the assassination of two Tunisian politicians. This led to their designation as a terrorist group by the Tunisian government in 2012. Following this, Abu Iyadh fled the country and declared his support for both Al Qaeda and ISIS. AST was also declared a terrorist group by the U.S. government in 2014.

(Text by Zebediah Millslagle)

Sources:

https://web.stanford.edu/group/mappingmilitants/cgi-bin/groups/view/547#note9

—-

Radhia Nasraoui

Radhia Nasraoui has established herself as the voice against torture in Tunisia. Torture during the Ben Ali regime was commonplace; a typical punishment for journalists or activists who opposed the regime.

Nasroui began her career working in a law office at the age of 23, where she first began convincing lawyers to defend students who had been convicted for protesting by the president at the time, Bourguiba. She proceeded to open her own firm, with the mission of defending any and all political prisoners, regardless of their background. In 2003, she cofounded the ALTT: the Association for the Fight Against Torture in Tunisia. This organization, although not officially recognized, publicly stands against torture, and provides aid for its victims.

She herself has been targeted by the government. She has been beaten brutally, dealt with constant death threats, and escaped several car “accidents.” Her family, too, has had to suffer harassment by the government.

She nevertheless maintains that “they will have to kill me to shut my mouth.”

(Text by Susanna Korkeakivi)

Sources:

http://www.cclj.be/actu/politique-societe/radhia-nasraoui-tunisiens-ont-depasse-peur

http://www.human-dignity-forum.org/2011/11/radhia-nasraoui-leading-the-fight-against-torture-in-tunisia/

——————————-

The Tunisian National Quartet

Formed in throughout the Summer of 2013 during a time of tension between the ruling coalition and opposition parties, the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet was charged with mediating during negottations, and played a critical role in consists of Tunisia’s predominate labor union, the UGTT, the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT), the Tunisian Union of Industry, Commerce, and Craftsmanship (UTICA), the Tunisian Bar Association, and the Tunisian League for Human Rights (LTDH). The national dialogue is intended to last until the “end of the transition” (Jadaliyya).

With increasing tensions between members of the Constituent Assembly, particularly after the assassinations of Chokri Belaid and Mhamed Brahmi, the drafting process was hindered in finalizing the constitution. The Quartet’s goal, consequently, centered around convincing parties across the political divides to realize compromise through a period of adversity (Guardian).

The narrative in media surrounding the Quartet and their actual actions do not always align. The Quartet is lauded for halting a “civil war,” which in truth was a conflict localized to the Bardo suburb of Tunis; the Quartet is often cited as a “model” for compromise and negotiations, yet the Quartet maintained a policy of “sign-first and discuss later” in regards to most of its formal resolutions. More than that, the Quartet explicitly did not include perspectives from youth in conducting its dialogues, and because of the youth’s centrality in organizing and participating in the revolution-movement, their exclusion from the Quartet is problematic. The Quartet did persuade “21 different political parties” to attend and deliberate in a national dialogue, intended to draw a “roadmap” for the political future of Tunisia. Yet the very notion of the Quartet as part of a more broad “Tunisian success story” may well be detrimental to Tunisia’s immediate political future, as the old regime boomerangs back into a dominant hold on politics today.

The Quartet has gained increasing international recognition, culminating with the winning of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2015. Likewise, international soft power played a critical role in the Quartet from its inception, with the group regularly meeting with and seeking counsel from European ambassadors. The Quartet, moreover, has no constitutional commitment towards representing public opinion — the suggestion of its forming a “pluralistic democracy,” as asserts the Nobel Peace Prize, thus becomes contradictory and a menacing portent for the future. (Nobel Committee). Indeed, the Nobel may work to further solidify the Quartet’s members as an institution in Tunisia, for better or worse.

(Text by Oakley Haight)

Sources:

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/09/who-are-the-tunisia-national-dialogue-quartet-nobel-peace-prize-winner

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2015/press.html

http://nawaat.org/portail/2015/10/17/the-tunisian-quartet-and-the-nobel-priz

http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/20129/the-quest-for-a-way-out-of-tunisia%D5s-constitutiona

Mohsen Marzouk

Mohsen Marzouk was born in 1965 to a poor blue collar family in the city of Sfax. As a student activist at the University of Tunis, Marzouk drew the eye of Tunisia’s secret police. He was arrested, tortured, and sent to work in a labor camp in Tunisia’s southern desert. Upon his return, Marzouk stayed politically active. Working to reinstate the General Union of Tunisian Students and eventually founding the Nidaa Tounes, Marzouk is a prominent force in the Tunisian Political scene.

Marzouk is charged with running external relations for the Nidaa Tounes. The Nidaa Tounes are a large secularist political party in Tunisia. The party’s founding leader, Beji Caid Essebsi, is the current president of Tunisia. Marzouk was his campaign manager during the election of 2014.

Mohsen Marzouk firmly believes in the separation of church and state, and fully supports a supportive and secular government. A man of action, and a fiercely opposed to the Ben Ali regime, Marzouk fights for the advancement of the Tunisian political system, “Tunisian civil society should change its methods and strategies if it is to contribute to starting and sustaining the democratization process.”

Currently the Secretary General of Nidaa Tounes, Marzouk, is leading the Tunisian fight against terror in the Middle East. He believes that fighting terror should be the top priority of the Tunisian government. “First we have to conduct this war against terrorism and then we have to reform our security institutions.” A leader in the Tunisian government, Marzouk, is continuing his fight for the security of his country.

(Text by August Peters)

http://www.dw.com/en/mohsen-marzouk-is-tunisias-democracy-failing/a-18887427

http://www.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2015/05/242648.htm

http://www.meforum.org/1973/dissident-watch-mohsen-marzouk

Hamma Hammami

Born in 1952 in El Aroussa, Tunisia, Hamma Hammami has been a vocal political activist in his home country since the early 1970’s. Originally studying to become a professor in Arabic literature, he would never find employment as a professor following his first arrest in 1972 after he was found participating in a student’s movement. 2 years later he was sentenced to an 8-year prison term for his association with El Aamel Ettounsi (The Tunisian Worker) an unauthorized association with dissident ideologies. Hammami served 6 of his 8-year sentence during which he was brutally tortured and left with permanent physical damage. As a result he left for France to find medical aid. During his time abroad he was tried for his connection to the Communist party of Tunisia workers (PCOT), which he had founded and was sentenced to 18 months. After a series of short term arrests Hammami went into hiding in 1992. In 1994 however, he was arrested by the police who consequently tortured, sexually assaulted and threatened to kill Hammami and prevented him from accessing medical assistance for some weeks. As a result many of the injuries he suffered during this assault still affect him today. Later that year Hammami was sentenced to 4 years in prison on charges of maintaining an unauthorized association, carrying false identification, and assaulting a police officer. In both of the trials held in 1994 he was not given a fair process as both his lawyers were blocked from calling witnesses and the judge ignored many other unorthodox procedural matters. For years after his arrest, Hammami’s family was harassed by Tunisia’s secret police who constantly surveilled the family and allegedly attempted to run over Hammami’s wife and kidnap his daughter.

In 1999 both Hammami and his wife were tried on a multitude of charges stemming from their involvement with the PCOT. A 4 day long show trial took place that, upon its conclusion, found Hammami and his co-defendants guilty resulting in a 9 year sentence for Hammami and a 6 month sentence for his wife Radhia Nasraoui. For months after the trial Hammami’s family was increasingly harassed as many of his extended family were exposed to death threats from the police as well as warrantless searches of their homes.

Since this sentence Hammami has been in and out of hiding but was arrested yet again on January 12, 2011 for giving statements to journalists regarding the Tunisian protests. He was held for a period of 4 days and released by the police.

After his release, Hammami declared his candidacy for the Tunisian presidential elections under the party known as the Popular Front. The Popular Front is a far left group with ideologies in line with those of Marxism and Socialism. Hammami ran in the election and attained 7.82% of the vote. After losing the presidential race, Hammami has undertaken the role of spokesperson for the Popular Front party.

(Text by Jack DeFrino)

http://gewerkschafterinnen.amnesty.at/Hamma.Hammami/chronology.html

http://www.tunisia-live.net/whoswho/hamma-hammami/

http://www.espacemanager.com/hamma-hammami-menace-la-rue-pour-descendre-le-gouvernement-si.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamma_Hammami

Ennadha

Ennadha is the Islamist political party that was the opposition party for decades during Bourguiba’s and Ben Ali’s regime. Ennadha grew out of the MTI party and supports a moderate Islamist agenda. Originally inspired by the Muslim Brotherhood, they believe in a civil society and believe that democracy and Islam can coexist. They also support women’s rights and democratic alternance (Marzouki). Their leader Rached Ghannoushi believed that the state should be separated from the way the people practice their religion.

During Ben Ali’s regime, party members were often jailed and the party was barred from participating. Ghannoushi was exiled, but returned after the Tunisian revolution. As a party that had always been in opposition to the old regime, the party fared well and won a plurality of seats in the 2011 elections, which were the first free and fair elections in Tunisia’s history (Guazzone). With 89 out of 217 seats, they played a large role in forming the coalition government that assumed power post revolution. They compromised to help write the new constitution, but believed that any major reforms would have to wait. The old regime police force and the judiciary remained largely in power. And the deteriorating socioeconomic conditions did not help their popularity amongst the people.

In the 2014 elections, Ennadha was forced to concede defeat to Nidaa Tounes. However, they had already agreed not to field a presidential candidate in order to allow for more sharing of power. They also agreed to join their main rival Nidaa Tounes in a coalition government, as Nidaa Tounes had won only 85 seats out of the 109 they needed to ratify the cabinet (Bryne). This move was far from consensual amongst party leaders and some criticized them for not following an Islamist enough agenda. However, they have recently been gaining support as Nidaa Tounes MP’s have been withdrawing from the party (Tarfa).

(Text by Caroline Guiot)

Sources:

Bryne, Eileen. “Tunisia’s Islamist Party Ennahda Accepts Defeat in Elections.” The Gaurdian. N.p., 27 Oct. 2014. Web. 21 Jan. 2016.

Guazzone, Laura. “Ennahda Islamists and the test of government in Tunisia.”The International Spectator 48.4 (2013): 30-50.

Lewis, Aidan. “Profile: Tunisia’s Ennahda Party – BBC News.” BBC News. N.p., 25 Oct. 2011. Web. 22 Jan. 2016.

Marzouki, Nadia. “Rom Resistance to Governance:the Category of Civility in the Political Theory of Tunisian Islamists”” The Making of the Tunisian Revolution: Contexts, Architects, Prospects. N.p.: Oxford UP, n.d. N. pag. Print.

Tarfa, Inel. “Nidaa Tounes Continue to Accommodate Ennadha and Continue to Alienate.” Tunisia Live. N.p., 11 Jan. 2016. Web. 21 Jan. 2016.

“Tunisia’s Ennahda to Join Coalition Goverment.” – Al Jazeera English. N.p., 1 Feb. 2015. Web. 22 Jan. 2016.

Higher Authority for Realisation of the Objectives of the Revolution, Political Reform and Democratic Transition

This group was a transitional authority of Tunisia right after the Revolution in Tunisia. The Tunisian Revolution, which is sometimes known as the Jasmine Revolution, lasted from December 17, 2010 to January 11, 2011. This committee was created in March of 2011, and was disbanded finally in October of 2011 once its purpose had been served. It purpose was to help implement reform in Tunisia, allowing for a more secure transition into a democracy post-Ben Ali. These reforms were primarily legal and constitutional, since the rights of many had been trampled upon during the previous regimes. The President of this committee was Yadh Ben Achour. Yadh Ben Achour had previously been President of the Higher Political Reform Commission (created by Mohammed Ghannouchi), which was merged with the Conseil de Defense de la Revolution in order to create the Higher Authority for Realisation of the Objectives of the Revolution, Political Reform and Democratic Transition and tried to attain all of the goals of reform for the new Tunisian state. The Conseil de Defense de la Revolution was made up of more than 28 different organizations including different political parties such as Ennahda and groups representing lawyers and judges. This group established rules about Constituent Assembly elections and created Instance supérieure indépendante pour les élections which implemented new rules and processes around elections in the country. All in all, this group was a fundamentally important part changing Tunisia’s political, legal, and constitutional scene once Ben Ali had fled the country.

Sources: http://www.hirp.tn/fr/index-composition-262-329.html

http://www.iris-france.org/docs/kfm_docs/docs/2011-03-tunisie-deux-mois-aprs-la-rvolution.pdf

http://maghreb.blog.lemonde.fr/2011/10/13/la-haute-instance-pour-les-objectifs-de-la-revolution-ferme-ses-ported/

The Truth and Dignity Commission (TDC) was launched in 2014 by the National Constituent Assembly (NCA) and is part of Article 17 of the transitional justice law which seek to investigate the injustices and crimes committed by the Tunisian state during the regimes of Habib Bourguiba and Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. The TDC was endorsed by then Interim President of Tunisia, Moncef Marzouki, president of NCA, Mustapha Ben Jaafar, and Prime Minister, Mehdi Jomaa. The commission’s mandate was to assign “judicial and non-judicial mechanisms” to investigate, reveal and establish the truth about the gross human rights violations that were committed during the tyrannical rule in Tunisia from 1956 up to the 2011 revolution. The timeframe of the investigation encompasses the torture, harassment and unjustifiable imprisonment of thousands of “trade unionists, students, leftists and Islamists by the dictatorships; and also the casualties of the 2011 revolution that sparked the Arab Spring.” The formation of the commission is one of the biggest successes of the Tunisian revolution in its transition to justice and democracy. If successful, the commission seeks to hold the perpetrators of the crimes accountable and prosecute them. The commission also promised to provide compensation to the victims. Since the launch of the TDC, people have flocked in numbers to submit their cases to the commission. So far, horrific stories have been reported to the commission. Some victims of the state brutality describe being “beaten unconscious, hung upside down, plunged underwater or into buckets of human waste, electrocuted, raped or sodomized.” Although the investigation process is very tedious and frustrating, Tunisians believe that it is a necessary step towards transitional justice and leaving it unaccomplished could allow old injustices to brew and possibly erupt into chaos. Former President Marzouki underscored the importance of the TDC “there can be no sustainable democracy without acknowledging and addressing mistakes of the past” he said at the luanch of the commission. Despite receiving overwhelming support from the international community, the TDC faces many challenges and its ambitious objectives could be in jeopardy as there had been reports of lack of political will, inefficiency, divisions, deep polarization and also numerous resignations from key members of the commission. The commission also faces bureaucracy and often confrontation with the police over access to government archives. In addition, the two rival political parties the Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes are also not fully cooperating in the process. Nidaa Tounes, for example, has been criticized for only seeking reconciliation and healing in the interest of national stability, but seem to care less in justice. Moreover, sympathizers of the old regime’s political and business elite have retained power and influence in the new democratic order. The election of President Beji Caid Essebsi in 2014, who held high ranking positions in both the Bourguiba and Ben Ali regimes and his party Nidaa Tounes party could pose serious obstacles to the commission. In one interview President Essebsi said that he would propose amendments to the transitional justice law. His government is in favor of reconciliation and amnesty to the corrupt elite who allegedly stole fortunes and committed egregious crimes under the shield of Bourguiba and Ben Ali. If granted amnesty, the perpetrators will escape justice. Sources Gall, Carlotta. “Torture Claims in Tunisia Await Truth Commission.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 19 May 2015. Web. 21 Jan. 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/20/world/africa/torture-claims-in-tunisia-await-truth-commission.html?_r=0 Jonathan Steele. “On the Eve of Its Launch, Tunisia’s Commission on Truth, Dignity in Turmoil.” Middle East Eye. N.p., february 2015. Web. 22 Jan. 2016. http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/eve-its-launch-tunisias-commission-truth-dignity-turmoil-213755480 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/11/attacks-state-tunisia-truth-commission-crisis-democracy http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/presscenter/articles/2014/06/09/tunisia-launches-truth-and-dignity-commission.html

The Truth and Dignity Commission (TDC) was launched in 2014 by the National Constituent Assembly (NCA) and is part of Article 17 of the transitional justice law which seek to investigate the injustices and crimes committed by the Tunisian state during the regimes of Habib Bourguiba and Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. The TDC was endorsed by then Interim President of Tunisia, Moncef Marzouki, president of NCA, Mustapha Ben Jaafar, and Prime Minister, Mehdi Jomaa. The commission’s mandate was to assign “judicial and non-judicial mechanisms” to investigate, reveal and establish the truth about the gross human rights violations that were committed during the tyrannical rule in Tunisia from 1956 up to the 2011 revolution. The timeframe of the investigation encompasses the torture, harassment and unjustifiable imprisonment of thousands of “trade unionists, students, leftists and Islamists by the dictatorships; and also the casualties of the 2011 revolution that sparked the Arab Spring.” The formation of the commission is one of the biggest successes of the Tunisian revolution in its transition to justice and democracy. If successful, the commission seeks to hold the perpetrators of the crimes accountable and prosecute them. The commission also promised to provide compensation to the victims. Since the launch of the TDC, people have flocked in numbers to submit their cases to the commission. So far, horrific stories have been reported to the commission. Some victims of the state brutality describe being “beaten unconscious, hung upside down, plunged underwater or into buckets of human waste, electrocuted, raped or sodomized.” Although the investigation process is very tedious and frustrating, Tunisians believe that it is a necessary step towards transitional justice and leaving it unaccomplished could allow old injustices to brew and possibly erupt into chaos. Former President Marzouki underscored the importance of the TDC “there can be no sustainable democracy without acknowledging and addressing mistakes of the past” he said at the luanch of the commission. Despite receiving overwhelming support from the international community, the TDC faces many challenges and its ambitious objectives could be in jeopardy as there had been reports of lack of political will, inefficiency, divisions, deep polarization and also numerous resignations from key members of the commission. The commission also faces bureaucracy and often confrontation with the police over access to government archives. In addition, the two rival political parties the Ennahda and Nidaa Tounes are also not fully cooperating in the process. Nidaa Tounes, for example, has been criticized for only seeking reconciliation and healing in the interest of national stability, but seem to care less in justice. Moreover, sympathizers of the old regime’s political and business elite have retained power and influence in the new democratic order. The election of President Beji Caid Essebsi in 2014, who held high ranking positions in both the Bourguiba and Ben Ali regimes and his party Nidaa Tounes party could pose serious obstacles to the commission. In one interview President Essebsi said that he would propose amendments to the transitional justice law. His government is in favor of reconciliation and amnesty to the corrupt elite who allegedly stole fortunes and committed egregious crimes under the shield of Bourguiba and Ben Ali. If granted amnesty, the perpetrators will escape justice. Sources Gall, Carlotta. “Torture Claims in Tunisia Await Truth Commission.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 19 May 2015. Web. 21 Jan. 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/20/world/africa/torture-claims-in-tunisia-await-truth-commission.html?_r=0 Jonathan Steele. “On the Eve of Its Launch, Tunisia’s Commission on Truth, Dignity in Turmoil.” Middle East Eye. N.p., february 2015. Web. 22 Jan. 2016. http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/eve-its-launch-tunisias-commission-truth-dignity-turmoil-213755480 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/11/attacks-state-tunisia-truth-commission-crisis-democracy http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/presscenter/articles/2014/06/09/tunisia-launches-truth-and-dignity-commission.html

UTICA

UTICA (Tunisian Union of Industry, Trade and Handicraft) is an employers’ union representing businesses in the industrial, trade and handicraft sectors. Founded in 1947, it represents more than 150,000 private businesses – mostly small and medium in size. It also has more than 25,000 union officials. UTICA’s presence spans across Tunisia, with 24 regional unions and 216 local unions. UTICA aims to promote investment and innovation in its sectors, as well as collaborating with the Tunisian government to promote the interests of small and medium business owners.

On 9<sup>th</sup> October 2015, the National Dialogue Quartet – composed of UTICA, the Tunisian General Labour Union, the Tunisian Human Rights League and the Tunisian Order of Lawyers – was announced as the laureate of the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize for “its decisive contribution to the building of a pluralistic democracy in Tunisia in the wake of the Jasmine Revolution of 2011”. The Norwegian Nobel Committee noted the National Dialogue Quartet’s crucial role in ensuring a Constitution that guaranteed fundamental rights for all Tunisians, regardless of their gender, religious affiliation or politic beliefs.

Before the revolution, UTICA played a more ambivalent role in its relations with the government. In January 1977, UTICA and the UGTT (General Workers’ Union) signed a “social contract” with the Bourguiba government in an effort to maintain social mobility. However, this social contract detiorated by the end of 1977, in light of increased tension between the government and the Unions.

<a href=”http://www.utica.org.tn/Fr/notre-mission_11_27″>http://www.utica.org.tn/Fr/notre-mission_11_27</a>

<em>From Socio-Economic Protest to National Revolt: The Labor Origins of the Tunisian Revolution</em> by Sami Zemni in <em>The Making of the Tunisian Revolution</em> by Nouri Gana, 2013

<a href=”http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2015/press.html”>http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2015/press.html</a>/

Text by Elliott Miller

Beji Caid Essebsi

On December 31, 2014 Beji Caid Essebsi became the 4th president of Tunisia. Winning 55.68% of the vote, over rival interim president Moncef Marzouki, Essebsi became the first regularly elected president after the toppling of the Ben Ali regime. With the election of Essebsi, Nidaa Tounes gained control over both the parliament and the executive branch of the Tunisian government. Nidaa Tounes is a leftist secular party that Essebsi founded on June 16, 2012. Essebsi is both founder and chairman of Nidaa Tounes but, under constitutional law, has had to cut ties with the party while acting as president. While being a popular party among many Tunisians, Nidaa Tounes, along with Essebsi, has been criticized for being too close to the old regime. This criticism is based on Essebsi’s controversial political past.

Caid Essebsi was born on November 26th, 1926. He was educated at the Faculty of Law in Paris, where he received a degree in law. After graduating in 1950 he began to practice law in Tunisia in 1952. Under the first Tunisian president Habib Bourguiba, Essebsi acted as an adviser to the president until he was appointed regional director of the Ministry of Interior in 1963. Essebsi continued to hold a variety of cabinet positions under Bourguiba until Ben Ali’s coup in 1989. Under Ben Ali’s regime Essebsi became the president of the Parliament from 1990 to 1991. With the toppling of the Ben Ali regime in 2011, Essebsi was appointed Prime Minister of the interim government. As Prime Minister, Essebsi was given the task of organizing the transitional government. Essebsi only served from February to December, 2011, at which point he was replaced by Hamadi Jebali. Essebsi went onto form Nidaa Tounes and run for president in 2014.

Essebsi spent much of his political career serving the dictator that the 2011 uprising removed. Many critics see his election as the returning of the old regime. Yet, the results of Tunisia’s first free elections have been respected by all parties and praised by many international governments. The stability of the transition of power between Essebsi and Marzouki shows hopeful steps towards a strong and stable democratic future.

(Text by Sam Wood)

Source:

http://www.wsj.com/articles/beji-caid-essebsi-wins-tunisian-presidency-1419262908

http://www.tunisia-live.net/whoswho/beji-caid-essebsi-2/

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-tunisia-election-idUSKBN0JZ04F20141222

Independent High Authority for Elections (ISIE)

The Tunisian Independent High Authority for Elections or in French, Instance Supérieure Indépendante pour les Élections (ISIE) was founded in 2011 to be a credible and independent observer, overseer, and organizer of the Tunisian elections in the new democracy. The original mission of the group was to oversee the elections of the National Constituent Assembly, but it was later established as a permanent fixture to oversee all future elections in Tunisia. The ISIE has a very straightforward structure. There is a council and an executive body. The council has all of the decision making power. There are nine members of the council, who are elected by the National Constituent Assembly. Of the nine, there always has to be a:

- Judicial Magistrate

- Administrative Magistrate

- Lawyer/notary/bailiff

- University professor

- IT engineer/security expert

- Communications specialist

- Public finance specialist

- Member representing Tunisians abroad

Members of the ISIE council are elected for six-year terms, and can only serve once. Every two years, three members of ISIE are rotated out, so that there is constant variation within the organization. The executive body is in charge of administrative, financial and technical matters, and is headed by an executive director. The ISIE council can create regional taskforces to assist in work before elections or referendums. The regional authorities must be approved by an absolute majority of the ISIE council and can be composed of no more than four people. The ISIE and its members can also be held accountable in case of misconduct, and are required to publish reports on elections on a regular basis.

Through this process of credible delegation and running of elections, ISIE has been widely applauded globally for its effectiveness in successfully running the post-revolution Tunisian elections.

(Text by Jacob Simon)

Sources:

http://aceproject.org/ace-en/topics/em/electoral-management-case-studies/tunisia-the-independent-high-authority-for-the

http://www.iri.org/resource/tunisian-elections-historic-step-forward

http://www.tunisia-live.net/2014/10/27/international-observers-commend-tunisias-elections-an-extraordinary-achievement/

Image from Wikipedia

Al Irada

Al Irada, one of the newest political parties in post-revolution Tunisia, was formed by former Tunisian president Moncef Marzouki on December 20th 2015. Marzouki created Al Irada in the wake of his defeat in the 2014 presidential elections to help address the multiple crisis facing Tunisia. Marzouki claims that Nida Tunis, the current leading political party, has compromised Tunisian confidence in the government through false promises and “has no future”[1].

Marzouki claims the roots of Al Irada lies with his efforts to “continue the Tunisian dream”[2]. Additionally, the party aims to address terrorism, the party’s main grievance with the current government. As of December 21st 2015, the country has suffered 3 attacks by extremist group the Islamic State. Marzouki claims the growing numbers of Jihadists in the region are “the children of the dictatorship”[3]. Marzouki plans to lead the party for a year or two and then hand the reins over to the younger members.

[1] http://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2015/12/20/former-tunisian-president-marzouki-launches-political-party-attacks-government

[2] http://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2015/12/20/former-tunisian-president-marzouki-launches-political-party-attacks-government

[3] http://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2015/12/20/former-tunisian-president-marzouki-launches-political-party-attacks-government

(Text by Carsen Winn)