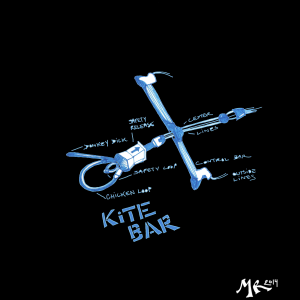

These are some photos of myself kiting last summer and this winter. The drawing is a diagram of a kite bar, which I hope the reader finds helpful for some context. The top left photo is a silhouette of Simon, maybe on his way to a better place.

*** The Launch ***

Summer 2005

If the wind is blowing up the Nantucket harbor, there’s a predictable crew of boardshort-clad kite-flying maniacs crossing the channel between two stretches of sand known as Bass Point and Pocomo.

When I was a kid, we’d pile in my family’s little low-railed 19-foot Bristol Skiff and go out for a day of wakeboarding, tubing and sunbathing on the point. Crossing the channel we got soaked by sea spit, and I’d squint up to the sky through salty tears at a brightly colored heavy-duty polyester monster attached to a human pilot skillfully flying the beast from the waves. I told myself I was going to be one of those maniacs some day.

Summer 2013

Now, at almost 20 years old, I’m ready. My cousins have already started kiting, one of them, Xander, is sponsored by Big Winds, a kiteboarding and windsurfing supply company in Hood River, OR.

With his gangly, lean build and jet-straight blond hair falling into his face, Xander is the ultimate extreme sports bum. He trains in freestyle snowboarding during the winter months and can be found in the surf on summer days when there isn’t wind.

I get tired of watching Xander and the rest of the “maniacs” launch 5 – 20 feet in the air from my towel on the shore. I start asking him about the equipment and how it works. I ask him to show me how to fly a trainer kite, a smaller version of a full sized riding kite.

My dad has already ordered a bunch of kiteboarding gear in anticipation of this summer season. I whip out a four-meter-long fluorescent-green inflatable kite and pump it up using the hand pump, which works like a bike pump but has a winder air cylinder.

I close the valve check the pressure of the kite by flicking the large tube on the leading edge, listening for a satisfactory high-pitched “ping” noise. I then unwind the bar and attach all four lines to the tips and leading edge of the kite. Ready to go.

Xander takes the bar in his harness and demonstrates some quick turning maneuvers. Alright, looks easy enough. I clip into the harness and take the bar in my hands. I turn down on the right side immediately thrusting the kite into the sand. It dives hard with the sound of the wind ripping across the polyester canopy before landing with a hollow thud, scattering sand granules in every direction.

I’m not discouraged, I manage the kite back into the air and toggle the bar gently keeping the kite right above me, where the wind has the least power. I nervously dip the right and left sides of the bar, practicing just barely catching the wind, afraid to lose control.

I spend a lot of my time learning this sport in fear. Fear of crashing, drowning, and not knowing what was lurking in the depths beneath me when I’m out in the water. I come to understand that my worry is a product of my own lack of confidence. I spend most of my days watching experienced kiters soar while I continuously crash and burn my body into the sand, but I keep my head up and my stubbornness prevails.

*** Double in over my head ***

July 2013

Gasping for air, squinting through salty tears I reach for the depower loop and yank down on the center-line. I toggle the bar and the kite relaxes. I’m no longer being pulled down wind half under water. I catch my breath and look behind me for my board.

I see Simon headed towards me in his red inflatable, one hand on the steering wheel, one hand grasped around my board.

He was a professional ass saver. Even if he was getting paid for it, he treated me like a friend in need, always approaching my distress with a smile. The grin was usually a mix of amusement and approval for my efforts.

Until I got control over the kite, every day presented the opportunity to half drown myself, be thrown into the waves a high velocity, or have my body rubbed raw as I got dragged through the sand. The worst was having my feet sliced open by fragments of shells waiting like land mines amongst the throngs of seaweed on the sandy floor.

Learning to kiteboard was the ultimate mental and physical test. I spent the first month largely questioning my sanity. Simon was my guide.

He’d take me out in bad conditions just so I would have a chance to fly, I worked a long day job and had limited chances to get on the water. On some days we’d be out in the path of a thunderstorm and he’d reassure me, “If you can learn to fly in this shit, you’ll be able to fly anywhere no problem.” My confidence was often restored only by comments like that. He gave me a reason to keep trying.

He’d motor after me in the red inflatable as I’d be getting dragged down wind towards the other side of the harbor. One afternoon we looked over our shoulders at a wall of massive storm clouds. “We should probably get out of here,” Simon casually suggested.

He jumped out of his small craft, as usual he displayed signs of mild hypothermia: pale lips, shaky hands and hunched shoulders as he jogged through the wet sand in my directed to help. As I worked to detach the bar and get out of my harness, I looked up after about 30 seconds and Simon had already deflated my kite and half wrapped up my lines. Inadequate would be an understatement of my feelings at that moment.

He usually wore nothing but a sweatshirt as he piloted the small red inflatable. He never seemed to give one single fuck about the condition of his extremities after exposure to hours of sea spit and chilling winds. After a long day, I could see the lines of salt plastered across his cheeks and over the crown of his cleanly shaven head.

*** Simonas Agintas ***

Nantucket, MA

He always looked sort of wide eyed, which was exaggerated by the slight redness and irritation from hours of squinting past the sun over the salt water. Simon’s graying five o’clock shadow and cleanly shaven head didn’t hide well the years of sun that were reflected by a permanent tan and excess laughter lines in the corners of his face.

His office for the summer was a small red inflatable with slow leaks in her hull. His office phone, an iPhone safeguarded by a bulky buoyant bright-orange case, was tied securely around his neck with a piece of nylon chord, he hardly ever missed a text message.

I wade through the shallow water with my kiting gear under arm. Not looking where I’m going, I bring my right foot down on a razor sharp fragment of conk. I don’t even bother inspecting it until we’re loaded. On our way across the harbor Simon sees me ogling the massive flap of skin hanging off my heel and immediately lifts his own foot.

“Check this out,” almost showing off the soles of his feet covered with patches of electric green goop that effectively seal up the wounds inflicted from a summer’s worth of run-ins with broken shells and sharp rocks. Over the drone of the engine and whip of the wind at our ears I ask,

“Where can I get some of that?”

“Dunno, it’s some weird Soviet Russia medical shit,” Simon had a way of finding creative solutions for odd problems that this sport often presents.

Later in the summer when I’d go out kiting myself, surrounded by other riders and boats, I still only felt safe if his red inflatable was somewhere in sight.

Seeing him and others kite across the harbor was my inspiration for getting into the sport. It simply looked like too much fun to miss out on.

With Simons help, I worked all summer to get into the lineup of up-wind riders off Bass Point, I’ll never forget when he traded in the rescue boat for a kite and board of his own and flew out to join me and the rest of the lineup. We exchanged smiles and thumbs-ups as we crisscrossed our wakes back and forth off the point.

I couldn’t have dreamed up a better confirmation that I had become independent. I didn’t have to say goodbye to Simon now that our lessons were a thing of the past. Instead I had the gratification of honing my skills while I flew along side him, watching and learning from his moves. He would fly out in front of me, demonstrate a power turn and I’d follow mimicking his movements and nailing the skill on the second of third try.

*** Lessons in “dicking” around ***

Nantucket, MA

There’s a good reason that kiteboarding, as a sport, has only just graduated from the status of infancy to toddler. It’s arguably one of the less financially accessible sports out there. The average kite price is anywhere between $800 to $1,200 US dollars, add a ±$500 bar, ±$300 harness and ±$400 board and you’ve got yourself a good chance at filing for bankruptcy.

Though, after ownership of the equipment is taken care of it’s pretty much a free ride from there on out. Kiting equipment is built to last. The kite canopy is constructed of a heavy-duty polyester blend. Pressurized inflatable tubes line the leading edge of the kite giving it rigidity. The inflate and deflate ports are sealed off by rubber and plastic valves with Velcro reinforcements to keep the kite from exploding after a crash. Each seam in the polyester canopy is laminate sealed and reinforced with stitching.

The control bar and the lines act as a complete system that forms a connection between a harness and the kite. The ends of the bar each have a line that connects to the two outermost edges of the kite. From the center of the bar two lines merge into three to form connections on the inner left and right sides as well as the center of the leading edge of the kite. Anchoring the centerlines to the harness through an eye port in the center of the bar is a depower line. The depower line allows a rider to control how much lift the kite has by just slightly changing the length of the centerlines, therefore altering the angle of the kite canopy. This is important for maneuvering the kite, without the intention of riding. It is almost impossible to body drag up wind with the kite fully powered after losing the board from a crash.

The depower line ends in a highly complex technical contraption known as the “chicken loop.” Simon always had a hard time getting the words “chicken loop” out. He would kind of bob his head forward as if to force out the phrase as he said it. Instead of “chicken loop” it sort of sounded like “ch-ii-ckon l-ou-pe.” Anyway, it’s a rubber-coated cable that hooks into a bent metal latch at the center of the harness and is secured by another technical piece referred by most kiters as the “donkey dick.” The dick, another rubber coated device, slides between the metal latch and the loop to lock the two into place and prevent slippage even in the presence of tricky maneuvers.

The harness is a fancy contraption comprised of technically sculpted foam and neoprene with durable canvas seams and adjustment straps. The latch that closes it shut around the rider’s waist is made of steel, so is the bent latch that holds the chicken loop. The harness is equipped with a hide-away, easily accessible knife to sever the kite lines in a life-threatening snare with another kiter or boat.

Lastly, there’s the all-important board that allows the rider to glide over waves and currents. Though, this January I’ll be using a snowboard to maneuver over frozen lakes and fields.

*** Winter Hunger ***

December 2014

The seasons change, birds fly south and the water gets cold. I wake up to the sound unmistakable scraping noise of facilities personnel shoveling snow outside of my dorm window. The fresh dusting glimmers on the rooftops in the morning light.

Kiting equipment now under lock and key in the storage unit, an idea spawns. I call my dad and have him pack the gear in the back of the big green adventure machine that is soon to leave Nantucket for a trip north.

On island, the sea is cold and black with the sinister tides of winter, but here in Vermont thick sheets of ice form in the dropping temperatures and cap the lakes. Snow is falling in droves and the campus is in full frosty winter-wonderland effect.

I unpack the back of the Land Rover and haul the massive bag full of kiting equipment into my dorm where it will get stored under my bed until the start of J Term.

I open up the MASSkiting website, an online forum for kiteboarders around New England. I peruse through the “events” tab one the home page and find one “Tug Hill Snowkiting” session. The gathering is this February in a wind farm located in Lewis County, NY.

Suddenly my insane dreams of using my kiteboarding gear in the winter are brought down to earth by the fact that there are people out there who actually do this thing!

I set out to start contacting local experts on the sport. Multiple people tell me about previous sessions they’ve had in snowy fields around New York and Vermont. I learn that there are actually some great spots on lake Champlain once the ice freezes solid and snowfall accumulates. Finding members of this niche community over the next month should be an adventure on its own.

*** Localize the focus ***

Jerri Benjamin, St. Albans, VT

Jerri, donned in snowshoes and masked with ski goggles, bright orange plastic sled in tow, meets me in the Sandbar State Park lot down the currently inaccessible road to what she calls her “camp.”

“I brought this for any equipment you might have,” she says with a muffled voice underneath the protection of her neck gator. “I sure hope you’re Morgan.” I place my large camera bag in the sled. “Snowshoes or crampons?” Jerri asks holding up the two options.

“Uh, I’ll try the crampons.” I struggle to wrap the rubber mesh of the metal studded accessories around my boots with the limited dexterity offered by my warm Gore-Tex mittens. It’s below freezing with the added chill of high winds coming off the frozen lake. Jerri bends down to help me, while I stumble and nearly fall over. I notice her bare hands and feel even more like a rookie.

Jerri pulls a photo of her tiny blonde grandson off the side of the fridge. His stance is wide atop a soft top short board, small fists clenched intently around a bar hung up in the backyard that simulates steering a real kite. Nash is sporting a T-shirt, the grass is green around his feet and the sunlight looks warm. Nash seems as far away as the summer months of the photo he stands in, I wasn’t thinking then that I’d get the chance to meet him just a few days later. I turn and look out through Jerri and Curt’s bay windows across the frozen expanse that makes up their front yard. Retired, they live on St. Alban’s bay, an inlet off Lake Champlain. Jerri puts on a pot of hot water for tea while my cheeks thaw from the short journey across the ice from where I left my car.

I’ve come out here to pick Jerri’s brain for advice on finding good locations where I can exercise my winter kiting skills this January. Jerri owns and runs Northshore Kiteboarding Lessons out of the basement garage of her small lakeside home. She’s been cruising over frozen ice and snow with the use of her kiting equipment for a few years now.

“I like to go out with the guys, we sometimes kite around this island out here.” She points out the window at a small tree covered lump of land emerging out of the ice. “They’re a little braver than I am so I usually let them go around first while I wait to see if the ice is thick enough,” she admits with a bashful grin.

I respect her worry; there are many places close to shore and between the islands where the ice can be unpredictably thin. Jerri cautions, “It’s good to ask locals like the ice fisherman about conditions before you head out, the ice is never safe.” I trust her judgment and heed her warning as I plan my own expeditions out onto frozen lakes and open snow covered fields later this month.

Nash Benjamin, Middlebury, VT

“Hey Nash, can you tell me about your drawing.”

Two and a half vertical feet of blue-eyed, toe-head-topped toddler stumble proudly across the living room to a drawing pad currently turned to an impressively accurate compilation of scribbles that actually looks like a kiteboarder riding a “bihg way-vuh.”

“Nash loves kiteboarding,” says Jordan with a tone of affirmation in his son’s direction. “We watch a lot of surf movies.”

Three-year-old Nash has just woken up from his afternoon nap with a burst of excited dialogue about all things ocean. Erin even kited in the early stages of her pregnancy with Nash, he was born to dream about kiting. Until he’s old enough to get out there himself, he tends to jump on top of any surface that looks like a board and rides it like he’s got a wave underfoot.

“Where did all da waves go, papa?”

“No waves today, Nash,” It’s the middle of January in the middle of Vermont.

Spencer Sherman, Colchester, VT

“On the week days I’m Mr. Mom,” said Spencer on the other end of the line as I try to coordinate a time to meet up with him and check out the ice cover on Lake Champlain.

I turn into a driveway marked by a “Helpful Healing Chiropractic” sign. A tall individual with silver streaks in his beard greets me in the doorway of his covered porch. I walk inside and am immediately offered a tall glass of the green-brown contents of his blender. I willingly take the vessel and fearlessly sip on the heath-nut sludge, not bad. Spencer’s son, Isaac, has some of the goop dried and plastered to his cheeks, he proceeds to energetically climb all over the kitchen counter tops. We spend half an hour indulging Isaac by playing with his train sets and reading books before I get the chance to ask Spencer about what I’m actually there for. Finally snow boots and jackets are on as the three of us head outside to the garage.

The door opens revealing a silver mini cooper with a license plate that reads “SPINE.” He pulls the car out and reveals a wall of wooden shelves stock piled with kites, boards and other equipment. Spencer whips out what looks like a regular snowboard, but he flips it over revealing a special feature.

Glare ice is impossible to get a grip on while kiting using a snowboard, so some guy out in Minnesota invented this thing called a switchblade. The switchblade gets bolted to the heel edge of the board. It’s essentially a modified hockey skate, which cuts into the ice giving the Spencer an edge that can grip the frozen surface of a lake even if there is no snowfall. I am meeting Spencer later in the week to head out over the lake, if we get finally get some more snow.

*** The crapshoot weekend warrior ***

January 19, 2014

Friday morning, hot tea and banana in hand, I jump in the big green adventure machine at 7:34 AM to start my journey in search of better snowfall. With the early morning light chasing me west over the bridge to New York, justification for my long excursion from Vermont is restored as I look down at a not-so-frozen Lake Champlain. The back of the car is packed with three kites, two snowboards, a helmet, harness, kiting lines, boots, and a variety of digital camera paraphernalia.

In the parking lot outside a Dunkin Donuts I wait on a phone call from Christo, a snow-kiting instructor whose number I found on the internet. We’ve never actually met, all I know is that his heavy eastern European accent and familiarity with kiteboarding reminds me of Simon, which somehow translates to trust.

I’ve arrived in Lewis County, NY, situated on a geographic feature known as the Tug Hill Plateau. This area is famous for not much more than its heavy snowfall and high winds, “lake-effect” weather that comes off of Lake Ontario.

I realize I have driven nearly five hours to an unknown place to meet a man I know nothing about. Before I left, most of my friends kept giving me looks like I was crazy or saying, “hold on, you’re going to do what?” I didn’t have much of an answer for them either. The whole weekend is a bit of a crapshoot idea.

The phone rings, it’s Christo. He tells me to keep driving west on Route 12 North, past a lodge and onto Route 177 through a wind farm, stopping at Deer River Ranch.

I pull my car next to a Honda SUV outside a large red barn on the side of the road. I get out and peer in the windows of the empty Honda to find brightly colored canvas bags in the back seat. I made it. I don’t even bother unloading before I cross the road to the adjacent field and walk over the crest of a hill to find three small black figures next to big brightly colored kites. Kiting is an individual sport, but it’s nowhere near as fun when you can’t share the conditions with other enthusiasts. Stoke levels are stronger in numbers.

I approach the guys with little hesitation, none of them are Christo, he is still on his way. Like I said before, crapshoot weekend.

I introduce myself to Phil, Brian and Steve. All middle-aged guys who thought they were out for a boys weekend, until I showed up.

I have little consideration for their agenda as excitedly I set up my lines and pump up my nine-meter kite.

Jerri was really excited when I called her up and told her I was a kiter. The sport is already small and there’s an even smaller network of women who are willing to get out there. Of course, I do a great job of proving myself with a display of kite crashing and face plants before finding my rhythm and footing out in the fields. The bumpy, ice-ridden grass doesn’t quite compare to the glassy salt water I learned on this past summer, but I don’t care. Simon always told me that the worse the conditions are, the better I’d get as a kiter. “No one ever learns to kite on glassy water with clean wind,” he’d say. So here I am in a snowy field with sporadic patches of grass and predictably horrible lulls and gusts in the wind, loving every damn minute of it.

The guys are really great though, Brian and Steve are experienced kiters and they’re on telemark skis so they have a lot of maneuverability. They keep coming by and helping me re-launch my kite when the wind dies. As a snowboarder, I can’t really walk around with the kite that well, so they show a little mercy.

Surprisingly, there are some inherent differences to kiting in sub-freezing conditions as opposed to kiting in 75 and sunny beach weather. For starters, instead of gracefully slipping my bare toes out of the sand and into the cushy straps of my kiteboard, I have to clumsily wrench my tightly bundled feet into the bindings of my snowboard while attempting to keep control of my kite in volatile wind gusts.

This weekend reminded me of something Jerri said earlier this month. She told me that she likes the sport because it forces us to collide with other people. It’s a one-man deal once we get flying, but on the ground we can’t avoid asking other kiters or willing onlookers to help us with a launch or discuss local conditions and safety techniques. There’s an inherent community around the sport and we find ourselves looking out for, or putting faith in people we’ve just met, because we really don’t have a choice. It’s about chasing after something we love and being willing to form connections with those who share the thrill, even if they’re total strangers.

*** Dedication ***

This project is dedicated to the life of, Simonas Agintas “Simon” (1981-2013), my mentor and friend. He was senselessly taken from this world on the night of November 23rd while defending himself from the advances of an armed robber at his house in the small beach town of Paracuru, Brazil.

There are people who cross our paths, drawing us to them with a deep passion for life, leaving on us an impression we can’t ignore. Once a stranger to me, he opened his heart and shared his love for kiteboarding. He taught me how to channel my fears into strength of mind and body. This project has been a process of healing and recognition of the imprint he left before his death. His spirit remains with the wind and I swear I can still hear his voice whenever it howls.